|

|

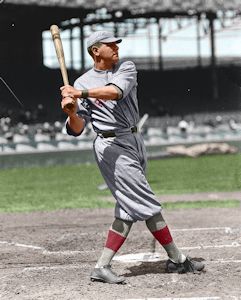

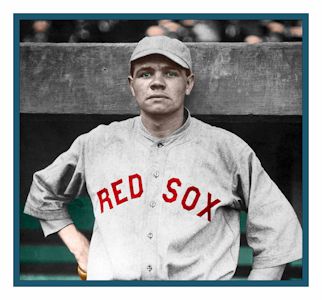

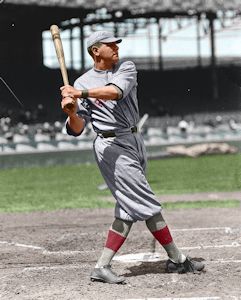

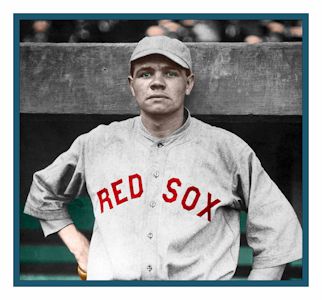

1919 |

Although Babe Ruth didn’t play every day with the Red Sox until May 1918, the idea of putting him in the regular lineup was first mentioned in the press during his rookie season. Calling Babe “one of the best natural sluggers ever in the game,” Washington sportswriter Paul Eaton

thought Ruth “might even be more valuable in some regular position than he is on the slab—a free suggestion for Manager Bill Carrigan.” The Boston Post reported that summer that Babe “cherishes the hope that he may someday be the leading slugger of the country.”

In 1915, Ruth batted .315 and topped the Red Sox with four home runs. Braggo Roth led the AL with seven homers, but he had 384 at-bats compared to Babe’s 92. Ruth didn’t have enough at-bats to qualify, but his .576 slugging percentage was higher than the official leaders in the

American League (Jack Fournier .491), the National League (Gavvy Cravath .510), and the Federal League (Benny Kauff .509).

With the Red Sox offense sputtering after the sale of Tris Speaker in 1916, the suggestion to play Ruth every day was renewed when he tied a record with a home run in three consecutive games. Ruth hated the helpless feeling of sitting on the bench between pitching assignments, and

believed he could be a better hitter if given more opportunity. In mid-season, with all three Boston outfielders in slumps, Carrigan was reportedly ready to give Babe a shot, but it never happened. Ruth finished the 1917 season at .325, easily the highest average on the team. Left

fielder Duffy Lewis topped the regulars at .302; no one else hit above .265. Giving Ruth an everyday job remained nothing more than an entertaining game of “what if”—until 1918.

The previous summer, the United States had entered the Great War; many players had enlisted or accepted war-related jobs before the season began. Trying to strengthen the Red Sox offense, about two weeks into the season, manager Ed Barrow, after discussions with right fielder and team

captain Harry Hooper, penciled Ruth into the lineup. On May 6, 1918, in the Polo Grounds against the Yankees, Ruth played first base and batted sixth. It was the first time he had appeared in a game other than as a pitcher or pinch-hitter and the first time he batted any spot other

than ninth. Ruth went 2-4, including a two-run home run. At that point, five of Ruth’s 11 career home runs had come in New York. The next day, against the Senators, Ruth was bumped up to fourth in the lineup—he hit another home run—where he stayed for most of the season. Barrow also

wanted Ruth to continue pitching, but Babe, enjoying the notoriety his hitting was generating, often feigned exhaustion or a sore arm to avoid the mound. The two men argued about Ruth’s playing time for several weeks. Finally, after one heated exchange in early July of 1918, Ruth quit

the team. He returned after a few days and, after renegotiating his contract with Frazee to include some hitting-related bonuses, patched up his disagreements with Barrow.

Ruth then began what is likely the greatest nine or ten week stretch of play in baseball history. From mid-July to early September 1918, Ruth pitched every fourth day, and played either left field, center field, or first base on the other days. Ruth’s double duty was not unique during

the Deadball Era—a handful of players had done both—but his level of success was (and remains) unprecedented. In one 10-game stretch at Fenway, Ruth hit .469 (15-for-32) and slugged .969 with four singles, six doubles, and five triples. He was remarkably adept at first base, his

favorite position. On the mound, he allowed more than two runs only once in his last ten starts. The Colossus, as Babe was known in Boston, maintained his status as a top pitcher while simultaneously becoming the game’s greatest hitter. Ruth’s performance led the Red Sox to the

American League pennant, in a season cut short by the owners, partially because of dwindling attendance. All draft-age men were under government order to either enlist or take war-related employment—in shipyards or munitions factories, for example—which led to paltry turnouts of less

than 1,000 for many afternoon games that summer.

While with the Red Sox, Ruth often arranged for busloads of orphans to visit his farm in Sudbury for a day-long picnic and ball game, making sure each kid left with a glove and autographed baseball. When the Red Sox were at home, Ruth would arrive at Fenway Park early on Saturday

mornings to help the vendors—mostly boys in their early teens—bag peanuts for the upcoming week’s games. “He’d race with us to see who could bag the most,” recalled Tom Foley, who was 14 years old in 1918. (Ruth was barely out of his teens himself.) “He’d talk a blue streak the

whole time, telling us to be good boys and play baseball, because there was good money in it. He thought that if we worked hard enough, we could be as good as he was. But we knew better than that. He’d stay about an hour. When we finished, he’d pull out a $20 bill and throw it on the

table and say ‘Have a good time, kids.’ We’d split it up, and each go home with an extra half-dollar or dollar depending on how many of us were there. Babe Ruth was an angel to us.”

To management, however, Ruth was a headache. His continued inability—or outright refusal—to adhere to the team’s curfew earned him several suspensions and his non-stop salary demands infuriated Frazee. The Red Sox owner had spoken publicly about possibly trading Ruth before the 1919

season, when Babe was holding out for double his existing salary and threatening to become a boxer. However, Ruth and Frazee came to terms and the Babe’s hitting made headlines across the country all season long. He played 111 games in left field, belted a record 29 home runs, and led

the major leagues in slugging percentage (.657), on-base percentage (.456), runs scored (103), RBIs (114), and total bases (284). He also drove in or scored one-third of Boston’s runs.

|