|

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||||

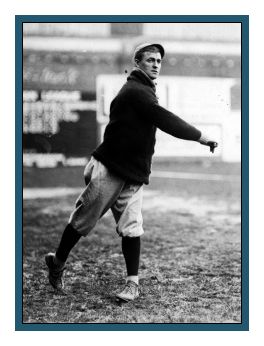

Buck O'Brien had bounced around New England pitching semi-pro ball for many years. He finally played the Connecticut State League Hartford Senators and stood out as one of the top hurlers in the league, notching 20 wins against 10 losses in 1910. With his success, Buck’s contract was scooped up by the Red Sox and he was assigned to the Denver Grizzlies of the Class A Western League where he tossed a no-hitter. By early September, he led the league in strikeouts with 261 and his 26-7 record ranked him second in games won, helping lead the Grizzlies to a pennant. When Buck was finally called up to the Red Sox, he beat the Philadelphia A's in his first start. He signed a $4,200 deal in 1912 and pitched in the opening game at Fenway Park in April, but didn't perform too well. On May 21st. The Cleveland Naps' great left-handed pitcher, Vean Gregg, and O’Brien engaged in one of the finest pitching duels of the season, with Buck coming out on top, 3 to 1. He finally got in a groove and won five of his six through the end of June. On July 13th he shut out Ty Cobb and the Tigers, 4-0. August ended with a superb pitchers' duel between Buck and the Philadelphia ace, Jack Coombs, in a game the Sox won 2-1. As eyes across baseball grew transfixed on Joe Wood’s staggering 34 victories, O’Brien quietly amassed a series of impressive outings in his own right, notching seven wins in eight starts to bring his record to 20-13 by the end of the season, as the Sox easily coasted into the World Series against the Giants. Buck took the mound at Fenway Park against Rube Marquard in Game #3. In a hotly-fought pitchers’ duel, he threw well but was nicked for two runs as the Giants walked off the field with a victory. With the Sox up three games to one and the fifth game being played at the Polo Grounds, Sox owner Jimmy McAleer wanted the series to go back to Boston so he could get the gate receipts. He ordered manager Jake Stahl to start O'Brien instead of Joe Wood, who he wanted to pitch back at Fenway and would bring in a huge crowd. > McAleer's interference angered Stahl, yet pleased many of the gamblers who circled the World Series like vultures. The possibility of one more game meant one more chance for a big payday. The fans were also visibly disappointed, as many had bet money on the Red Sox to win the fifth game. Not knowing that he was going to pitch, Buck was hungover the day of the game. Two scratch hits, a stolen base, and a balk, gave the Giants a run. He then completely came unglued and the Sox were down 5 to 0 before they even came to bat. Rube Marquard held down the Sox for an easy 5 to 2 Giants victory. It was a humiliating defeat and a major turning point in his career. He disintegrated in front of the fans’ very eyes. As he sat quietly on the train back to Boston, Joe Wood sauntered by his seat. Joe's brother Paul, angered by losing a $100 bet, picked a fight with O'Brien, and in a flash, the two were at each other’s throats. They were pried apart with Wood wielding a baseball bat after Buck punched him in the face. After the Sox took the Series and the players celebrated, Buck just packed his bags and headed home. By the spring of 1913, 30-year-old Buck O’Brien was a ballplayer in his prime, and his fighting spirit had not diminished. He once again stumbled out of the gate but, he seemed unable to find his rhythm and control. But he was not helped by his slumping teammates, and open warfare between Buck and other members of the team soon exploded. He struggled and in July was sold to the Chicago White Sox. Only a few players were able to cash in on their fleeting notoriety. Buck, who had a great singing voice, along with Hugh Bradley, and Marty McHale hit the vaudeville circuit and toured the far reaches of New England, where the sight of a bona fide major leaguer was a novelty. Harnessing the notoriety he gained with the Red Sox, Buck continued performing his old stage numbers in variety shows for the better part of a decade. Over the next few years, he pitched for one minor league club to the next. When his playing days were over, he worked with the Boston Parks Department as a coach and director of baseball clinics. In the summer of 1934 the O’Brien family suffered a major setback when Buck fell from the roof of a two-story building into a nest of barbed wire. He suffered massive injuries to his chest, neck, and face and was rushed to the hospital, where he required several bouts of surgery and hundreds of stitches. He remained in intensive care for several weeks. There were doubts that Buck would ever work again and, according to his daughter, he was out of work for nearly two years. Over the years Buck continued to battle a variety of ailments, and on the morning of July 25, 1959, his daughter arrived at his Dorchester home to take him to a scheduled medical appointment. Buck never made it. En route to the doctor’s office, Buck suffered a massive coronary occlusion and died. He was 77.

Buck

O’Brien was gone, but he would not be forgotten. Three years after his death, he

was again honored, this time at Fenway Park, where the surviving Speed Boys

returned in April 1962 to mark the 50th anniversary of the championship summer

of 1912. In acknowledgement of the first man to throw a pitch at Fenway Park,

the honor of throwing out the ceremonial first pitch fell to Buck’s 9-year-old

grandson, Tommy O’Brien.

|

|||||