|

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||

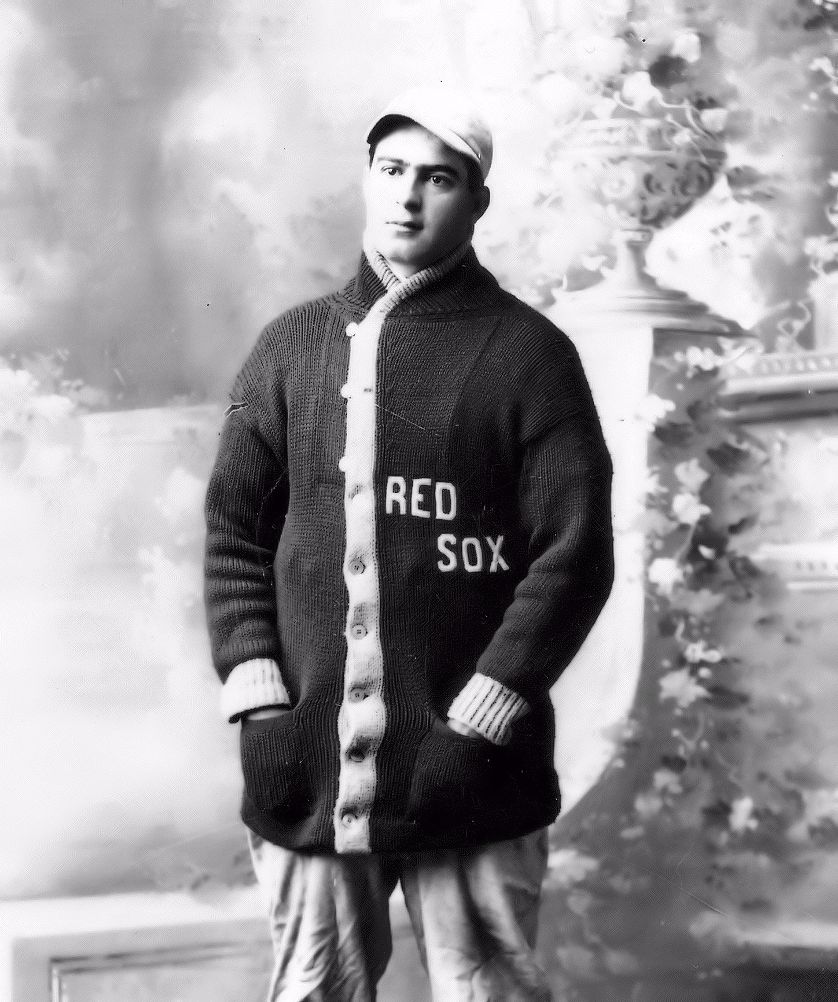

Standing 6-feet-1 at 185 pounds with dark good looks, the young Charley Hall cut an imposing, often intimidating figure on the mound. Early in his baseball career, he combined his “swarthy” appearance with a blazing, high-voltage fast ball. Later, with diminished speed but more consistent control, he deftly packaged a wide array of pitches thrown at various speeds, alternately teasing and jamming hitters. Batters simply did not like to face either the young or old Charley Hall. Charley was born on July 27, 1884, in Ventura, California. His roots were Spanish-American. Both Spanish and English were spoken in his boyhood home. Charley started playing organized baseball as a boy. According to the Oxnard Courier, he “learned how to play ball” as a member of an Oxnard junior baseball team known as the Palm Street Nine. Very thin as a youngster, Hall’s prodigious baseball talent was not generally recognized until he began to mature physically. In 1904, Parke Wilson, the manager of the Seattle team in the Pacific Coast League, “discovered” and signed the 19-year-old Hall playing in Santa Barbara. Initially, Wilson used Hall in relief. As he gained experience and other veteran Seattle pitchers faltered, Charley became a starter as well. By July 1904, Charley’s record was 12-5, second best in the entire PCL. The Seattle Times called him “about the biggest sensation in the Pacific Coast League this season.” Opponents also noted his nerve. By the end of 1904, Charley had accumulated a 29-19 record, pitching a phenomenal 425 innings. Returning to Seattle again in 1905, Hall found himself on a horrible team. Burdened with the high expectations he established in 1904, he slumped – though he did no-hit Oakland on April 5. As the team improved, Hall rallied, finishing the year with a 23-27 record. He completed another marathon eight-month PCL season with 449 innings pitched. Although clearly overworked at times by the brutal schedule, Charley was rewarded for his diligence with over 870 innings of professional pitching experience in his first two years. When the 1904 and 1905 seasons ended in early December, Charley went home and played semiprofessional baseball in Southern California. He would do this for most of his professional career. Within this local, low-pressure, entertainment-oriented baseball environment, Charley also began coaching third base. His Spanish-laced baserunning instructions were high-volume exhortations that usually resulted in making him hoarse over the course of a game. Later, when he did the same thing as a Red Sox third base coach, the Boston fans affectionately named him Sea Lion. On May 13, 1906, against Oakland, Hall pitched his second no-hit game, winning 3-0. The Seattle Times called it “the finest exhibition of pitching seen in Recreation Park (Seattle’s home field).” A walk in the second inning and an error by the shortstop in the ninth accounted for Oakland’s only baserunners. Relying primarily on his fastball, Hall struck out seven. In July 1906, Charley finally got his first chance in the major leagues, reporting to the Cincinnati Reds. For Seattle, he had a 1906 record of 8-14 in 196 innings with an earned run average of 2.29. In Cincinnati, finished his rookie year with a 4-8 record in 95 innings with a 3.32 ERA.In 1907, he started with Cincinnati and things quickly deteriorated. His pitching control remained inconsistent. He would be impressive in one appearance and then wild in another. After pitching 68 innings in 11 games with a 2.51 ERA, Hall was sent to Columbus in the American Association. He ended the year with Columbus going 8-3. Hall began 1908 pitching for a Columbus team that finished in third place. He went 8-21, allowing 245 hits in 243 innings. It was his worst full-season record in professional baseball. Hall’s slide into baseball oblivion, however, suddenly ended when he was sent to St. Paul at the end of the 1908 season. At St. Paul in 1909, Hall was 4-13 with a 4.08 ERA in 172 innings. The highlight of his 1909 season was another no-hitter, a nine-inning effort against Louisville, which he eventually lost 1-0 in the 12th inning. He struck out every man in the lineup (six in a row) for a total of 16 batters in 12 innings. In the first nine innings, only two batters reached base, both on walks. At St. Paul, however, Charley had the good fortune to pitch for one of the legends of minor-league baseball, manager Mike Kelley. On July 26, 1909, Kelley got Charley back into the major leagues when he traded him with pitcher Ed Karger to the Boston Red Sox for pitchers Charlie Chech and Jack Ryan, plus cash. With Boston, Hall compiled a 6-4 record that season, pitching 59⅔ innings with a 2.56 ERA. In 1910, Charley pitched well as both a starter and a reliever for Boston. In his 35 appearances, he started 16 games and relieved in 19. His resulting record was 12 wins and 9 losses in 188⅔ innings with his major-league career low 1.91 ERA, good enough for 10th best in the American League. Hall’s 1911 role put more emphasis on relief pitching. His 32 pitching appearances included 22 in relief and 10 starts. He finished 1911 with an 8-7 record in 146⅓ innings and a 3.75 ERA. After Boston’s disappointing fourth-place finish in 1911, Charley showed up for 1912 spring training “lively and limber.” In 1912, Charley flourished, achieving major-league career bests in wins (15) and innings pitched (191). He appeared in 34 games, 20 as the starting pitcher and 14 in relief. 23 This was a distinct departure from his 1911 usage pattern, when he started only 10 games during the entire season. Hall made important contributions to the Red Sox’ 1912 championship season. He got the win in the first game at Boston’s brand new Fenway Park, replacing wobbly starter Buck O’Brien and pitching three-hit ball for seven strong innings to allow the Red Sox to rally in the 11th. During the first 35 games of the season, Charley appeared nine times and pitched four complete-game victories. On September 10, he saved Smoky Joe Wood’s 15th consecutive win in the ninth inning at Comiskey Park in Chicago. Hall was a consistently positive presence during the 1912 pennant drive. He voluntarily manned Boston’s third-base coaching box, often yelling directions and encouragement to his teammates. In the clubhouse, he was gregarious and friendly, often exchanging friendly banter with other veteran players. He often teased Boston pitcher Ed Cicotte (before the latter's July sale to the White Sox) that his name meant “punk” or “very poor” in Spanish. Cicotte jokingly insisted that Hall’s real name was Carlos Cholo. The 1912 World Series afforded Charley an opportunity to play against his two longtime Southern California friends, Fred Snodgrass and Chief Meyers. He appeared twice and was probably under the weather each time. The Boston Globe reported before the Series opener that Charley had a severe cold and it was uncertain to what extent he could pitch in the Series. He was referred to the Boston team physician, Dr. Cliff, for treatment. Sick or not, Charley performed. He pitched in the Game Two 6-6 tie, entering in relief of Ray Collins in the eighth inning with runners on second and third, one out, and the Red Sox ahead 4-3. He retired the first hitter but gave up a two-run double to Buck Herzog. Although walking the bases full, he pitched a scoreless ninth. In the 10th, he allowed a leadoff triple and the sixth Giants run. Hall also pitched in Boston’s seventh-game loss (because of the tie, the Series ran to eight games). He relieved Wood in the second inning and pitched the rest of the game.30 His World Series line showed 10⅔ innings pitched with a 3.38 ERA. After their pennant-winning 1912 season, the Red Sox players, including Hall, suffered a letdown in 1913. Within an environment that included distracting 1912-related celebrations, injuries, management turmoil, a strong wire-to-wire pennant run by Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics, and Boston’s erratic starting pitching, Hall’s workload changed. Appearing in 35 games, he was used as a relief pitcher 31 times and as a starting pitcher only four times. He ended the year with a 5-4 record in 105 innings with a 3.43 ERA. He failed to win any of his four starts and walked nearly as many hitters (46) as he struck out (48). After the disappointing 1913 season, Boston released him. Charley finished a 22-year professional baseball career with 54 major-league and 285 minor league wins, for a total of 339. After leaving baseball, Hall returned to California, where he owned land and was an avid outdoorsman. He entered law enforcement and served as a policeman, a jailer, and the deputy sheriff. In 1920, his family suffered a devastating loss when their 6-year-old son, Charley, accidentally shot and killed their 3-year-old son, Kenneth. In 1943, Charley died of Parkinson’s disease in his beloved Ventura.

|

|||