|

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||||

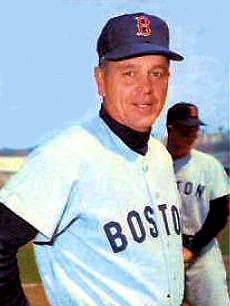

Dick Williams's intense competitiveness and versatility earned him 13 years as a major league utility player. He parlayed those strengths into one of baseball's most successful managerial careers, though not one of the winningest, and the record suggests that he was probably one of the two finest managerial turnaround artists between Joe McCarthy and Lou Piniella. As a rookie manager, he inherited a Boston Red Sox team that had finished ninth in the ten-team American League for the previous two seasons. He and his coaches improved them by 20 wins, and took them to the 1967 World Series. He was only the second manager in baseball history2 to win pennants for three different teams (Boston, Oakland and San Diego). His no-nonsense, aggressive personal and tactical approaches electrified the fortunes of other franchises. In Williams's first year with the Oakland A's, 1971, they won the A.L. Western Division championship, then won the '72 and '73 World Series. The expansion Montréal Expos responded to his guidance to be in a position to go to their first-ever playoffs in 1981, though he was fired before the end of the season. And the skipper pushed what had been arguably the most underachieving expansion franchise in baseball history, the San Diego Padres, to their first World Series after a 13-year history with only one campaign at or above .500. He ranks 18th on the all-time managerial win list with 1,571 wins and 1,451 losses over 21 seasons. Richard Hirschfeld Williams was born on May 7, 1929, in St. Louis, the second of two children. According to Williams's autobiography, No More Mr. Nice Guy, his father Harvey struggled through the Great Depression. While the hard-headed man was willing to work at whatever came up, if he didn't find any, he took it out on his boys in ways that today would be called child abuse. He taught the boys to be the most determined competitors at whatever they did or suffer his wrath. At the same time, Harvey Williams taught Dick to work with whatever came his way and that he should never try to escape accountability for every single thing he did. Williams's family lived with his maternal grandfather near St. Louis's Sportsman's Park, home to both the National League Cardinals and American League Browns. When Dick was 13 years old, Harvey Williams took his family to California, first to Hollywood and then to Altadena. Dick's formal athletic career started at Pasadena Junior College (then covering 11th and 12th grades followed by two years of college). He just about majored in sports, lettering in baseball, football, basketball, track, tennis, and swimming. In handball, he didn't just letter, he was city champ. He said was first noticed by Dodger scout Tom Downey in 1946, when Williams went from bleacher fan to emergency fill-in for the semi-pro El Monte team's center fielder, who was knocked out by a fly ball. The next year Williams signed his first pro contract with the Dodgers for a $1,200 bonus. After his twelfth-grade graduation, he immediately went to the Class C team in Santa Barbara, California. He got into 79 games as an outfielder, batting .246 with an adequate .115 isolated power mark and eight stolen bases. What he lacked in superstar numbers he tried to make up for in hustle and picking fights. The following year he attended his first pro spring training. It was an historic event, the premiere of Branch Rickey's industrialization experiment, Dodgertown at Vero Beach. Dodger management standardized drills and certified standards of accomplishment for every key fundamental a coach could measure. Dodger prospects got sunrise-to-sunset repetitive drills designed to teach the standard approaches to processes ranging from sliding into home plate to throwing to second base with a runner in scoring position. This fit well with Williams's natural predisposition to believe there was a right way to execute and that intensive commitment was the best way to reach a goal. And he started to internalize the drills themselves, adding them to the toolkit he would roll out later in less disciplined organizations. Back in Santa Barbara for the 1948 campaign, he chewed up Class C pitching (97 games, .335 average, 29 doubles, 16 homers, 16 steals, 90 RBIs), and was promoted to AA Fort Worth, where he was over his head (.207 average with .064 isolated power and no steals in 41 games). Perhaps it was getting used to AA pitching or meeting two of the most important people in his life, but in Williams's 1949 Fort Worth season, he played 154 games, and the best numbers in his pro career earned him All-Texas League honors: 109 runs, 30 doubles, 23 homers, 114 RBI and a .310 average. Between the 1949 and 1950 seasons at Fort Worth, Williams was back in the Los Angeles area working for money to subsidize his baseball career. He had an unusual temp job as an extra in a low budget movie, The Jackie Robinson Story. He played for the Almendares Alacranes (Scorpions) in the Cuban League in the winter of 1950-51. He was the only American on the Scorpions. But his Cuban League season ended prematurely February of 1951; he had to report for military training. A high-school football injury kept him from combat duty. A baseball injury in a camp game that same year got him a medical discharge. Minor leaguers returning from military service had to clear waivers before they could report back to their teams, and this reshaped Dick's playing career. He was claimed by both the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Cardinals. The Dodgers, determined to keep him, had but one option under the rules: bring the young outfielder up to the big club in Brooklyn. When he arrived in New York, he found himself, like the other bench players, shunned by the starters. The one vet who showed him encouragement was Jackie Robinson. They had already met, not because of the movie, but because Robinson was from Pasadena, too, and Williams was buddies with Robinson's older brother, Mack. On June 10, Williams debuted in a double-header against Pittsburgh. As the 26th player on a roster of 25 (Brooklyn did not have to count the returning military veteran against their 25), he eked out only 64 plate appearances for a team in a tight pennant race and with three accomplished starting outfielders in Carl Furillo, Duke Snider and Andy Pafko. While Williams was riding the pine, he did get experience that would serve him later. Manager Dressen kept the youngster close to him on the bench and taught him the fine Dodger tradition of bench-jockeying, at which Williams was a natural star. That also gave him a lever, a fulcrum and a place to sit and shadow Dressen's decisions. Dressen taught him another critical managerial lesson. Williams believes Dressen's palpable anxiety as the Dodgers' lead vaporized (13 1/2 games ahead on August 10, tied on the next-to-last day of the season) and the skipper's pacing and screaming and whining weakened the team's ability to hold the lead. Williams internalized the idea that the field manager needs to radiate calm confidence more than the shared worry. In 1952, league rules again required Williams again to be the 26th man, depriving him of the opportunity to play in AAA ball, where he could have built his skills. He could not be sent down until May 29, when his ex-serviceman roster status would expire. But as the date approached, he made a few fundamental plays Dressen appreciated, including a 3-7 putout of a runner at second base when he crept in from left field unnoticed after a bunt. Dressen decided to keep him, and in August started him in three consecutive games in St. Louis. In the third game, Williams raced in to throw himself at a dying quail off the bat of Vern Benson, dove, extended his right arm and heard a crack. It was a three-way shoulder separation that essentially destroyed his ability to reach his highest potential. His arm became a launcher of Texas League bloopers. Later, when he played third base, a manager told Dick to throw the ball to first on a bounce. Williams believed this career-sapping injury made him a good manager. And through it all, Dick Williams the player slowly became something else. He became someone who thought before he acted, who took nothing on the field for granted, who wanted to leave nothing on the field to chance. Slowly, painstakingly, in a process that took 12 years that began from the seat of his pants, he became Dick Williams the manager. He bounced between Brooklyn and the team's minor league system until the middle of the 1956 season, when the Orioles snatched him off the waiver wire. The O's, a losing team building themselves into a multi-decade behemoth and innovation factory, were led on and off the field by Paul Richards, a management titan and another important mentor for Williams. Richards loved having the full-tilt Williams on the team so much he acquired him through trades three more times: in 1958, 1961 and with the Houston Colt .45s, in October 1962. Williams had more than a few individual highlights in the next 8 1/2 years of his career. From 1957-61, playing for Baltimore, the Kansas City Athletics and Cleveland Indians, he notched at least 340 plate appearances each year, playing up to six positions. With his career winding down in 1962, Williams went from the Houston Colt .45s to the Boston Red Sox in a trade for Carroll Hardy. He played as a lightly-used utility man, getting into 140 games over the next two seasons. Boston was the American League's big-market team with the weakest front office. He got to witness, and despised, what he called the "country club" atmosphere. Fathered by owner Tom Yawkey and his royal court of drinking companions and yes-men, the organization was driven primarily toward pleasing Yawkey rather than pursuing excellence. The Red Sox hadn't risen above .500 for six years before Williams arrived, a frustration they extended the two years he was with them. Williams struggled to amp up the team's intensity from the bench, to teach them to hate losing as much as he did, but he believed he was associated with "a bunch of losers." While his playing skills were slipping at age 35, his intensity, flexibility and passion for observing and understanding caught the eyes of the Red Sox' minor league director Neal Mahoney and business manager Dick O'Connell. Mahoney invited Williams to manage a rookie team in a spring intrasquad game. After the Sox released Williams after the 1964 season, Mahoney offered him a player/coach position with the team's AAA affiliate in Seattle. When the farm team moved to Toronto during the winter, the Seattle manager, Edo Vanni, decided not to go. Mahoney gave Williams his first professional managing job as skipper of the Toronto Maple Leafs. It was enlightening for several reasons. First, according to Williams, he had to make the transition from bench jockey (criticizing others' mistakes) to accountability enforcer (judging his own). Given his hyper-critical father and his own similar tendencies, he worked to see no mistake went unanalyzed or uncorrected. Williams's relentless pursuit of excellence was rough on his players, rougher on opponents. He was doubly intense because he was working within the "country club" organization that, to him, represented the opposite approach. Second, he got to manage a lot of the young talent that would play for him in Boston, including 1965 International League batting champ Joe Foy, 1966 batting champ Reggie Smith, and catcher Russ Gibson. Williams led the Maple Leafs to International League championship in both 1965 and 1966, with records of 81-64 and 82-65. In those two seasons, the Red Sox finished ninth, 40 and 26 games behind. Business manager O'Connell became general manager and, agreeing with Williams about the corrosive "country club" atmosphere, decided to let manager Billy Herman go. The '66 squad had played at about .500 after the All-Star break, a possible indicator that with the right leadership, the team might be ready to excel. O'Connell had the choice of two successful minor league managers, Williams and Eddie Popowski. In September he chose Popowski as a coach and Williams to manage for the next season. O'Connell sensibly gave the rookie manager, at 37 the youngest in the league, the full off-season to prepare. From the first day of spring training, Williams made it clear that there would be only one person in charge -- him -- and there would be an avalanche of changes in management processes and rules. Williams stripped outfielder Carl Yastrzemski of his role as captain. All players who were single had to stay in the team's hotel, and players had to show up on time or be fined. With the standard practices he had learned with the Dodger organization as a basis, Williams stressed fundamentals. He didn't just borrow from successful precedents; he innovated, too. He was one of the first managers to use videotape for studying and coaching -- though he had to borrow the equipment from local television stations to execute his idea. Williams hated the way the Red Sox had conducted workouts in the past, especially for pitchers, who had a ton of slack built into their schedules. He sopped up slack by making all the pitchers play volleyball in the outfield, a drill that exercised footwork skills and pushed the competitive instincts of his athletes even during the laid-back environment of spring baseball. The games incensed spring training coach Ted Williams, and he went home. Things were different now, and as the manager noted, the Splendid Splinter was extremely happy to join the team's celebration when they won the pennant. Before the 1967 season began, Williams said, press and oddsmakers' predictions for the team were no different from years past. Williams promised that the team would "win more games than we lose." Opening day at Fenway Park only drew 8,000 fans, but by the end of the season all the home games were sellouts. Even with the new passion Williams injected, the team started 11-11, the same as it had the previous year. An injury to second baseman Mike Andrews forced Williams to use center fielder Reggie Smith as an emergency second baseman. The club slipped to 18-20 and sixth place by May 27. In a balanced league, a ten-game win streak in mid-July put them a half-game out of first place, brawling for the lead along with the Minnesota Twins, Chicago White Sox and Detroit Tigers. By August 17 they were in fourth place, 3 1/2 games behind the Twins. Their fate might have seemed sealed the following day when right fielder Tony Conigliaro, usually the team's clean-up or number five batter, was knocked out for the season by a fastball to the head. But O'Connell acquired a bevy of veteran subs to complement young José Tartabull as a replacement. Boston stayed in the race and took a one-and-a-half game lead, their biggest of the season, on August 30. On September 6, there was a four-way tie for first with 21 games to play. The Twins came to Boston for the final series of the regular season, leading the Red Sox and Tigers by a game. Many people expected Williams to start his ace, Jim Lonborg, on short rest, but the skipper decided to stick with his normal rotation. He needed to win both games, and Lonborg couldn't start both, so Williams sent gritty right-hander José Santiago to face everything the Twins could cobble together. The Twins scored a run in the top of the first, the Bosox caught up and passed Minnesota in the fifth, and then put the Twins away in the seventh on Yastrzemski's three-run homer. The 162nd game of the season was as dramatic. The winner would play in the World Series, with the Twins starting their best pitcher, Dean Chance, the Bosox their ace. Williams's infusion of relentless, aggressive baseball took hold. The Twins scored a run in the first and one in the third. With his team still down 2-0 in the sixth, Lonborg led off, and, on his own initiative, the 6'5" pitcher laid down a surprise bunt on the first pitch and legged it out for a hit. The Twins came apart: three batters, three singles, a run in and the bases loaded. The Twins replaced Chance with elite reliever Al Worthington, who uncorked a pair of wild pitches. The crowning blow was an error by first-baseman Harmon Killebrew. The inning ended with a 5-2 lead the Bosox would not yield. Yastrzemski went 4-for-4 to seal his Triple Crown (no one has led the league in batting average, homers and RBI in the same season since), and the team went 92-70, a 20-win boost from the previous year, to claim the pennant. In the World Series, Boston faced Red Schoendienst's 101-win St. Louis Cardinals, led by future Hall of Famers Bob Gibson, Lou Brock, and Orlando Cepeda. Even minus his clean-up hitter, Conigliaro, Williams played his hand well enough to take the Series to a seventh game, when Bob Gibson started, and won, for the third time, pouring it on with a complete game three-hitter and 10 strikeouts. The Red Sox' season was one of the great turnaround jobs in twentieth-century baseball history. It was the first of many Williams engineered. But successful management requires more than operational success. The country-club attitude Williams detested was an overarching ethos cast by owner Tom Yawkey. Williams recognized no privileged characters in the clubhouse, while Yawkey played favorites, granting special treatment to his pet players. Williams tried to enforce glacial emotions, not too high when winning, not too low when losing, a trademark of Paul Richards' methods. Yawkey was, Williams believed, a "front-runner" who would come to the clubhouse and share the good times, then duck and cover when the team was going badly. While Williams worked to suppress some of his intensity, everyone knew what he really thought. In spite of Williams's shaky relationship with the owner and his courtiers, his tightness with O'Connell and Mahoney insulated him. The three produced a benefit that ownership couldn't ignore. Boston had led the American League in attendance for the first time in more than 50 years, since Babe Ruth was a 20-year-old Red Sox pitcher, and had put more fannies in the seats than in the two previous seasons combined. The following season saw increased attendance but not wins. Baseball's 1968 campaign featured stifled offense that seemed a throwback to the Deadball Era. Pitching depth would shape the final standings more than usual. This worked against the Bosox in ways a manager couldn't control. Lonborg was injured while skiing in the off-season, and did not come back until late June. At that point Santiago's arm came up lame. Conigliaro, unable to recover from the beaning, was lost for the entire season. The team finished 86-76, in fourth place. Williams had led the Red Sox to their two best records since 1951, but the skipper wasn't behaving any more humbly toward the owner or the press. He was on a tight leash now, more vulnerable to office politics, without the victor's garlands to deflect the toxicity of the unhealthy organization. And the great Baltimore Orioles teams, built on the foundation laid by Williams's mentor Paul Richards, were blossoming, surging 15 wins while still falling short of Detroit that season. The Red Sox' performance in 1969 could not overcome the manager's poor relations with Yawkey and "his bobos." When he called out Yaz for a mental error on the basepaths and pulled him from the game as an object lesson to all, he smudged his relations with his squad. On September 22, with the team in third place at 82-71, Yawkey fled Boston for his South Carolina vacation home and had O'Connell tell Williams he was fired. Williams worked as Gene Mauch's third base coach with the Montreal Expos in 1970. After the season, though, he got an offer to manage again, with an organization that was 180 degrees from the Red Sox ethos. The owner who rescued him was Oakland's Charles O. Finley, a nonconformist, showman, and executioner of managers, even those who achieved winning records. Finley was as uninterested in conventions and niceties as Williams, and just as determined to win. While Williams had taken over a Boston team that seemed content with losing, Finley had collected an exaltation of talented young players. While the Boston team had finished next to last two years in a row, Oakland had had three straight winning seasons, the last two in second place in their six-team division. While Yawkey looked for a manager he was comfortable socializing with, Finley was interested in winning. Even with the A's recent success, he had changed managers eight times in eight seasons. The winners didn't win enough for his taste. Finley wanted it all. The 1971 Athletics lost four out of their first six games, allowing 40 runs in five of them. Finley was calling Williams every single day to co-conspire and wheedle and whine, and it was driving the manager nuts. A sophomoric practical joke by players on the team plane was the final straw. Williams had a meltdown, spewed some fire into the team, and either by design or coincidence, they won 12 of their next 13 games. By the thirteenth game of the season, they were in first place in their division. They stayed there, finishing 101-60, the franchise's best record since 1931. The 1972 season would deliver that victory, although not without a set of fights that filled the A's clubhouse with angry noise and the sports pages with lively reportage: Vida Blue vs. pitcher Blue Moon Odom, Reggie Jackson vs. first baseman Mike Epstein, Epstein vs. Williams, to name a small sample. The Brawling A's became a legend, underscoring the idea that a team didn't have to get along to go the distance. But Finley deserves some credit for his efforts in 1972. The A's won 93 games and were as balanced in their play on the field as they seemed imbalanced in their conduct off it: second in the league in runs scored (604), second-best in runs allowed (457), and second in defense (.732 defensive efficiency rate). Oakland defeated the Tigers in a five-game playoff series and faced Cincinnati's Big Red Machine in the World Series. The Reds were as balanced as the A's, second in runs scored, second in runs allowed, and second in defensive efficiency. They also featured tidier haircuts and clean-shaven faces. In the Series, Williams showed a range of extraordinary managerial moves. For one World Series, everything Williams decided turned to gold (and green). His dream of unquestionable, documented success that even his father would have found exhilarating was a tonic. In 1973, relations between the intrusive Finley and the skipper worsened. Williams, paid to be Finley's advocate with the players and the players' advocate with Finley, found playing go-between increasingly challenging, mostly because of Finley's conduct. For six years, the three under Williams and the three following, Oakland was almost a dynasty. Some of the players believe Williams was the element that made them so successful. In 1974 Williams was recruited by the California Angels' general manager Harry Dalton, at the insistence of team owner Gene Autry. This was not the free-spending Autry of the free-agency era who would explode into the winter player markets a few years later; this was the 13-year owner of a major-market team who Williams believed tried to get talent on the cheap, and who delivered teams that were middling at best. Regardless of the reasons for the dysfunction, Williams knew, in retrospect, it was a mistake, but Williams snapped at the suicide mission and lashed himself to the Angels' fate. In his first partial season, they went 36-48, at .429, little different from what his predecessor had been able to coax. Williams felt the team was imbued with a self-reinforcing culture of contentment in losing. The 1974 Angels had two ace pitchers, Nolan Ryan and young Frank Tanana, and almost no offense. With no batter who had hit 20 home runs, and with many fast, young players, Williams experimented with stealing bases and taking extra bases as the foundation of a strategy to create runs. The 1975 Angels finished 70-91, and for the first time in Angel history, ownership coughed up assets to acquire talent in its prime. Williams idled for the rest of the season. Near the end of it, he called the Montréal Expos executive John McHale, for whom he'd worked as a third-base coach in 1970, to ask for that franchise's managing job. It was a tasty prospect for a turnaround artist, and quite a difference from the environment in California: a different kind of organization, different country, different league. The 1977 Expos won 20 more games under Williams than they had the year before, on the bats and arms and gloves of young talent. Williams got them to be more patient (unusual for a team with so many young players) and they boosted their walks by about 10%; got them to run the bases aggressively (they surged to the league lead in doubles, for example), though with some offensive talent, he was not as wedded to the stolen base as he had been with the Angels. They improved to the middle of the pack in both pitching and batting. The 1978 squad improved by a single game, winning 76, while outscoring their opponents, 633-611. In 1979 the team joined the league's elite, bringing a balanced offense with power and speed and a pitching staff that blended the young and the old. From April 11 to the end of the season, they were either in first place or second, battling the Phillies and Cardinals, and after late July, the "We Are Family" Pirates. Montreal held on to the top spot as late as September 24 with a half-game lead. The Expos finished two games behind Pittsburgh, the team that proved to be the World Series winner. The season revealed an unusual aspect of Williams's management style. He wasn't biased against young players (or old), and he wasn't afraid to give a young player a chance to compete with an established veteran. 1980 proved to be a similar year. The Expos grabbed first place on June 11 and stayed in the lead until game 159. They were fourth best in scoring runs and fifth best in pitching. Their offense led the league in walks. But again, the young (this year even younger from an influx of prospects) Expos flagged in the home stretch. They fell short by a single game. The 1981 campaign would be Williams's last in Montréal. He believes the players were tired of him; he'd never stayed so long in a job. He feuded with several players, including newly acquired reliever Jeff Reardon. John McHale was uncomfortable with the skipper's tactical aggressiveness. While the team never got to another post-season series, the Expos had the best record in the majors when the owners forced a strike and Commissioner Bud Selig canceled the playoffs. Williams was still driven, perhaps more stoked than usual, by the premature finish to his Expo cycle. He had gotten the Red Sox and A's into World Series before his time expired. So in the ensuing off-season, when he was courted by the National League's sad-sack franchise, the San Diego Padres, he accepted the position. The Padres had 13 years of uninterrupted losing as a tradition, holding a death grip on the cellar seven of those years. San Diego had more talent than the Angels, but Williams saw the same comfortable-with-losing clubhouse. In Williams's first season, the Padres rose to .500 for the first time in their history. At 81-81, it was the equivalent of a 20-victory improvement over the shortened previous season's winning percentage. Dick had hammered some desire for winning into them, and they responded in all facets of the game. They climbed from eleventh to seventh in runs scored per game, becoming one of the most successful league offenses on the road, adapting to various environments. They moved from ninth to sixth-best in runs allowed, in part because the team went from ninth to first in defensive efficiency. The 1983 squad moved sideways, again with 81 wins, but the players were learning to understand the Williams game. For the 1984 season, after a seven-game losing streak that held them to an 18-18 start, the Padres began running on all cylinders. Williams believes the team responded either with anger at his chronic critique of mental mistakes, or simply from a desire to prove him wrong. A 15-5 run took them to first place on June 9 with a 33-23 mark. They didn't yield that spot through the end of the season, finishing 92-70. In the League Championship Series San Diego faced the Chicago Cubs, who made it to post-season play for the first in nearly 40 years of famous futility. The Cubs hammered the Padres in the first two games, and Williams's club looked and felt dead. But led in part by Garvey's heroics, Templeton's cheerleading and endless comebacks, the Padres won their first pennant. Their World Series opponent, the Detroit Tigers, had taken sole possession of first place in the season's fourth game, a position they would never lose, going 104-58. It was a balanced team that finished first in batting, first in pitching, and first in defensive efficiency. Detroit burned through the Padres in five games in what looked like a foregone conclusion from the first syllable of "The Star-Spangled Banner." Even with the disappointment of losing, it was a big win for the Padres franchise. For the third time, Williams had turned a chronic loser into a financial success; for the third time, a Williams team had set a franchise's attendance record (more than doubled in Boston in 1967, and more than doubled in Montréal in 1977 and increased 33% over the pre-Williams ceiling). In 1985, the Padres made it to the All-Star break just a half-game out of first, needing one more starting pitcher to keep up and the team struggled, finishing 83-79. The front office forced Williams out, making the announcement on the first day of spring training in 1986. Williams was enraged that the team's announcement made it look as if he had quit on his players, but he could not speak up because of a gag clause in his contract. Williams would be lured to one more major league managing position, yet again with a sad-sack franchise, the young and under-funded Seattle Mariners. Seattle brought him on 28 games into the 1986 campaign, and he led the team to a listless 58-75 mark, a little better than his predecessors. In 1987, his first full season, the Mariners achieved their best-ever record at 78-84. Ownership was generous, Williams believed, with one thing they shouldn't have been: unconditional love for the players. So his attempts to discipline went under-supported or even undermined. It would prove his downfall the following season. The M's best hurler was 26-year old Mark Langston, who believed he, not the manager, should decide when he came out of games. Williams could not brook this impertinence, but the front office backed the franchise's crown jewel, and Williams stubbornly campaigned for what all of baseball views as the manager's right. Forty-six games into the 1987 season, Williams was gone. The Mariners did not post a winning record until 1991, after new ownership took over and the young stars Ken Griffey Jr. and Edgar Martinez arrived. Williams never again managed in the majors. In 1990 he managed the West Palm Beach Tropicals in the Senior Professional Baseball Association, an attempt to put retired players in competition with each other in a league format. After that, he did occasional scouting for San Diego, gathering intelligence on AAA players when they played in Las Vegas, where he lived. He worked for George Steinbrenner and the New York Yankees as an adviser through 2002. Dick Williams's managerial career was remarkable within baseball, but the key talents that made him an exceptionally successful turnaround artist and leader are even more remarkable and precious in non-baseball management. He had the skill to use what resources were on hand. He was successful with different kinds of teams, not relying on a rigid protocol to be a roadmap to success. He could adapt his tactics to the roster he had, something few managers beyond baseball can do. At the same time, he was unafraid to take chances to improve his personnel. He was able to observe, monitor and analyze his young players, and successfully determine when the team would be able to take an immediate-term hit in experience as an investment in the development of a player who could become an all-star. Players who got their first chance under Williams, or who have stated he "taught me how to win," include Hall of Famers Gary Carter, Reggie Jackson, and Tony Gwynn. In December 2007, the Veterans Committee elected Dick Williams to Baseball's Hall of Fame. And which team's cap is he wearing on his plaque? Unsurprisingly, the cap of the franchise that, of all the ones he managed, had an owner most passionate about winning. He chose the cap of Charlie Finley's Oakland Athletics. In 1968, the team fell to fourth place when Conigliaro could not return from his head injury, and Williams' two top pitchers – Lonborg and José Santiago – were injured. He began to clash with Yastrzemski, and with owner Yawk Williams died of a ruptured aortic aneurysm at a hospital near his home in Henderson, Nevada on July 7, 2011. |

|||||