|

|

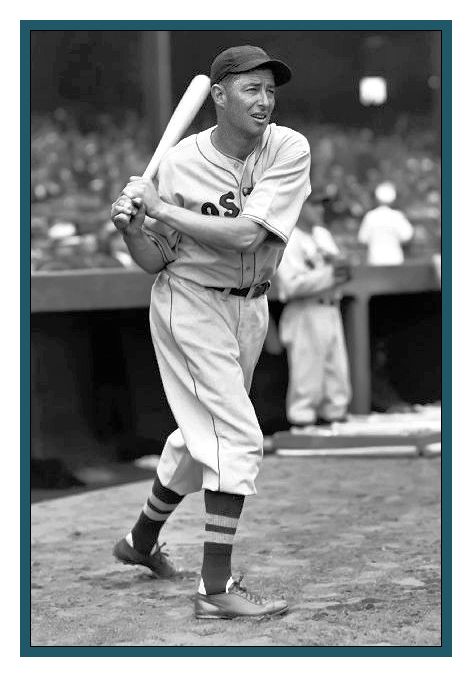

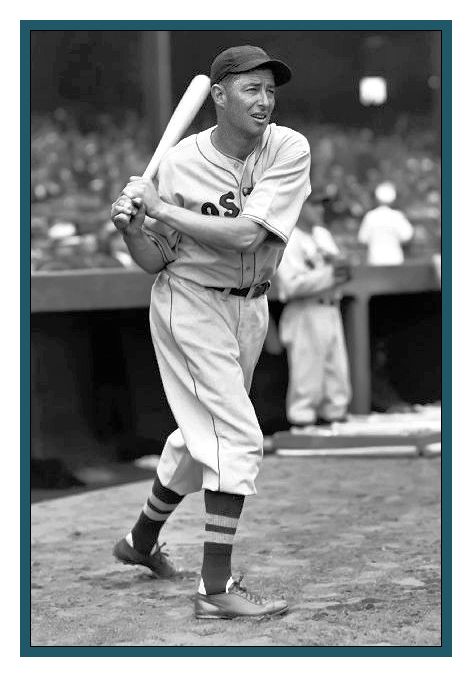

1936-1940 |

Like many businessmen in the aftermath of the 1929 stock market crash, legendary Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack took a beating financially and, as a result, he dealt his star outfielder Roger “Doc” Cramer to the Boston Red Sox. Cramer joined other Athletics stars such as

Lefty Grove and Jimmie Foxx in the exodus to Boston, whose much more financially secure Sox owner, Tom Yawkey, reaped the benefit.

Born in Beach Haven, in southern New Jersey, on July 22, 1905, Roger Cramer earned the appellation “Doc” because of his friendship while growing up with a local physician named Joshua Hilliard. Cramer religiously accompanied his friend and mentor on his house calls to patients, often

traveling on a “one-hoss dray” in nearby Manahawkin, where he and his family moved to when he was very young. He liked people calling him “Doc” but hated his other nickname, “Flit,” given to him supposedly by a sportswriter. By the age of eight, Doc had begun to follow baseball

obsessively, playing it as often as possible and watching many local games. He probably did not see any major-league games as a child or teenager, as his father did not share in his passion for the game. Perhaps Dad could not figure out why his son threw right-handed and batted

left-handed; to his family, this remains a mystery.

Doc Cramer first played baseball on the Beach Haven sandlots with his brother, cousins, and friends, and when he wasn’t making rounds with Dr. Hilliard he played ball constantly. When he was in high school (where he was an A student), he and family members even formed a baseball team

of their own, the Sprague and Cramer club. Doc also starred on the Manahawkin High varsity team; when not pitching, Doc played center field, second base, and catcher. He married his childhood sweetheart, Helen, on the day after Christmas in 1927 and they raised two daughters

together.

Still, Connie Mack, a former catcher himself, must have commiserated with the plight of his third-stringer, Cy Perkins, because on July 4, 1929, he permitted Perkins to take a day off and umpire a semipro doubleheader in southern New Jersey. All that Mack asked in return was that if

Perkins saw any talented athletes, he let the Athletics know about it. With that caveat in hand, Perkins slipped off to a twin bill between the Manahawkin and Beach Haven clubs. Perkins had advance knowledge that a special young man named Cramer might help out the major-league club. It

seems that some time earlier, Perkins and his teammate Jimmy Dykes had stopped by the office of a realtor named Van Dyke to look for some vacation property, and Van Dyke tipped them off to the local phenom.

It was in 1929, Doc Cramer began his professional career, in a Class-D minor league consisting of teams primarily from western Maryland. He hit .404 and won the batting championship. Although he had thrown 30-some innings over the course of the season, Cramer was a fixture in the

outfield. An oft-repeated tale, perhaps apocryphal, has Cramer copping the batting crown for himself. Apparently Connie Mack liked what he heard about the Blue Ridge batting champion because he secured him to serve as a reserve outfielder for the rest of the major-league season.

Cramer debuted on September 18 in a ninth-inning pinch-hit role against the visiting St. Louis Browns. An 0-for-5 game starting in left field against the Senators was his only other appearance. In all, Cramer came to bat six times without a hit in 1929. Doc accompanied the

Athletics to spring training the next year but did not make the cut when the A’s broke camp, being optioned to Portland in the Pacific Coast League. Doc hit so well at Portland (.347 in 74 games) that Mack called him up to for another viewing in mid-summer.

For the rest of the 1930 season, Cramer was a utility outfielder, working his way into 30 games and chipping out a .232 batting average. In 1931, Cramer played on one of the last of the great Philadelphia Athletics teams and his playing time incrementally increased -- 65 games and 223

at-bats for a .260 average. He hit his first major league home run, a solo shot, on August 16 and helped the club win the pennant. To round out this wonderful season, Doc came to bat twice in the World Series that year, getting one hit and two runs batted in as the Athletics lost to

the Cardinals in seven games.

In 1932, the Athletics failed to repeat, and Doc responded with a .336 average in 92 games. The country continued to suffer in the ’30s under its seemingly intractable Depression, and no team suffered more financially, despite relatively good attendance, than poor Connie Mack’s

Athletics - despite their excellent rosters and contending teams. Beset with financial issues, Mack began to sell or trade his stars to more prosperous clubs, or at the least more adventurous owners. Lefty Grove departed after the ’33 campaign, and Cramer took advantage of his

opportunities by batting .311. In 1935, Doc excelled again with a .332 average on a team increasingly unable to protect him in the order. Chronic economic difficulties continued to plague the franchise, compelling Mack to deal Jimmie Foxx and talented pitcher Johnny Marcum to the Red

Sox. Soon thereafter, Mack traded Cramer and then-promising shortstop Eric “Boob” McNair also to the Red Sox in exchange for $75,000 and throw-ins Hank Johnson and Al Niemiec. Cramer was voted onto the American League All-Star team each year from 1937 through 1940. He never forgot his

first major league manager, though; Doc loved Connie Mack, always considering him a second father.

In 1936, his first season with the Red Sox, Doc had a .292 average, although he hit no home runs that year and did not hit any for almost five years afterwards. He did improve his batting average though, with a .305 mark in ’37 and a .301 campaign in ’38.

On a personal level, Cramer flourished in Boston, his favorite city. No matter how famous or well-known Cramer became, he never forgot the times in his own youth when his family did not have money, so each year before Thanksgiving and Christmas, his wife would buy several bags of

groceries and load them into the family’s 1937 Chevrolet pickup truck. Then, Doc and daughter Joan drove to folks in town having a tough go of it. Obeying her father’s instructions, Joan would go to each house and drop off the groceries on the front porch, never knocking or ringing the

bell, and from there they would go to the next needy family until their rounds were complete.

In 1939, it was thought that the Sox might finally overtake the Yankees and win the American League pennant, a hope fostered greatly by the emergence of Ted Williams. No one had to tell Williams how great he was, but on one occasion Doc took exception to the rookie’s cockiness and threw a

punch at him in a vain attempt to inject him with humility. As a seasoned veteran, Doc could be expected to replicate his usual production.

Unfortunately, Doc began the season feebly, swatting away at virtually everything without success, and until mid-May his batting average hovered below .200. Exhibiting his frustration, he attempted to attain superhuman feats in the field, throwing himself into the center-field screen in a

vain attempt to snare a Hank Greenberg drive on May 4, and then days later performing a somersault in catching a “fierce liner” off the bat of Rudy York.

Finally, in a game against the Senators on May 14, he went 3-for-7 at the plate, raising his average to .213, thereafter becoming the Doc Cramer of old, with multi-hit games following swiftly after the breakthrough. By the end of the month, he had raised his average close to .300, but by

then manager Joe Cronin had taken him out of his customary leadoff spot, supplanting him with a slugging young second baseman named Bobby Doerr. Cramer was never a prolific base stealer despite being highly-regarded as a swift runner in the outfield. Some have wondered why Doc did not steal

more, although catchers threw him out frequently (he stole 62 bases but was caught 73 times). He was well-known as a singles hitter; one also wonders if he often did not try to go for the double and held up at first instead. During the remainder of the summer, Doc had his typical

year: strong defense, swift running in the outfield (but woeful in consummating steals), plenty of hits, but no home runs. It was a game against Detroit on the second of June, which seemed to exemplify Doc’s year, and indeed his entire career, in a microcosm. In an 8-5 loss, Doc went a

perfect 5-for-5 at the plate, a pretty rare feat, and yet the next day’s Sox headline in the Globe lauded the team’s manager/shortstop, trumpeting the fact that CRONIN POLES 2. Like Rodney Dangerfield, Doc got no respect, and his singles hitting paled in the face of power hitting

every time. Although the Yankees pulled away from the Red Sox and clinched the pennant in September, Cramer continued to play hard in what became, at best, a race for second place. His devotion paid off as he finished the season with a .311 average, a truly impressive statistic given

his glacial start at the plate.

As the threat of World War II increased the Sox gathered for the ’40 campaign, and Doc batted .303, but the winds had shifted at Fenway, with the advent of another pretty slick outfielder named Dom DiMaggio. Fenway has always been friendly to power hitters but less enamored of singles

hitters, and as he grew older, the home park became less tolerant of Doc’s style. Cramer loved Boston and wanted to keep playing there, but after 1940 the Red Sox traded him to the Washington Senators for Gee Walker. Doc always felt that Cronin traded him out of spite, as the two

strong personalities never got on. The same day, the Red Sox packaged Walker with pitcher Jim Bagby and catcher Gene Desautels in a deal with the Cleveland Indians for catcher Frank Pytlak, infielder Odell Hale, and pitcher Joe Dobson. Without the luxury of batting in the same lineup with

Williams, Foxx, and Doerr, Cramer saw his offensive levels drop off and he never hit over .300 again (he did hit .300 on the nose in 1943).

After 1953, Cramer left major-league baseball, spending most of the rest of his life as a carpenter. A very popular and humble man, he constantly had old ballplayers like Jimmie Foxx over to his house. Babe Ruth was a frequent guest of the Cramers and the Babe often carried a flask of

alcohol with him in his shirt pocket. Once Doc asked him to visit a young local boy who had recently lost a leg, and Ruth drove over with Cramer to visit the thrilled youngster. Doc Cramer died on September 9, 1990, after honoring 12 mailed requests for his autograph, in his beloved

Manahawkin, where a street is named after him today.

|