|

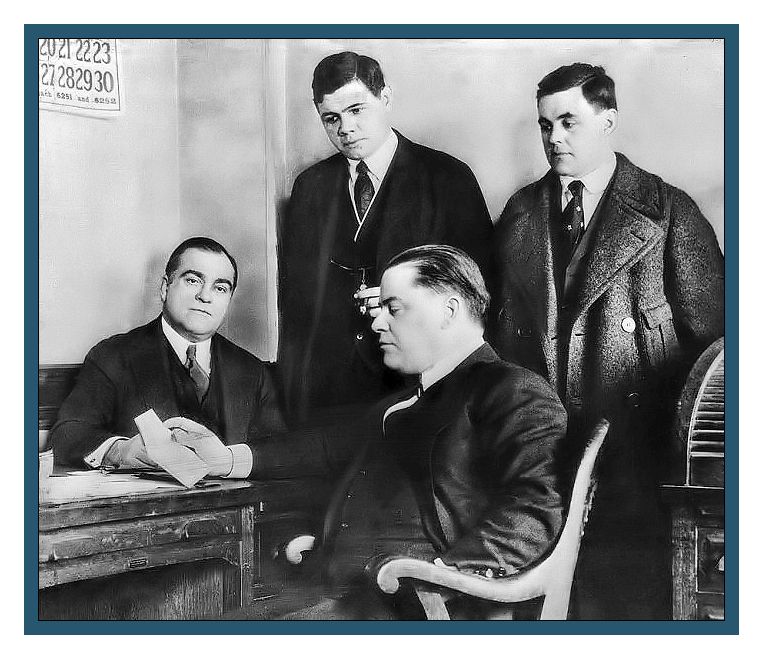

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||||

Most famous for his wildly successful tenure in the New York Yankees front office from 1920 through 1945, Ed Barrow left his mark on the Deadball Era as well. Though he never played a game of professional baseball, the ubiquitous Barrow was a key participant in the careers of countless players and a major actor in many of the era’s biggest controversies. The man who scouted Fred Clarke and Honus Wagner, moved Babe Ruth from the pitcher’s mound to the outfield, and managed the Red Sox to their last world championship of the 20th century also experimented with night baseball as early as 1896, helped Harry Stevens get his lucrative concessions business off the ground, and led an unsuccessful campaign to form a third major league with teams from the International League and American Association. In his official capacities, he served as field manager for both major and minor league teams, owned several minor league franchises, and served as league president for the Atlantic League (1897-1899) and the International League (1911-1917). Hot-tempered and autocratic, over the years Barrow crossed swords with Babe Ruth and Carl Mays, among many others. Harry Frazee, owner of the Red Sox during Barrow’s managerial tenure with the club, jokingly referred to his skipper as “Simon,” after Simon Legree, the infamous slave-driver from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. “Big, broad-shouldered, deep-chested, dark-haired and bushy-browed, [Barrow] had been through the rough-and-tumble days of baseball,” Frank Graham later wrote. “Forceful, outspoken, afraid of nobody, he had been called upon many times to fight, and the record is that nobody ever licked him.” Edward Grant Barrow was born on May 10, 1868, in Springfield, Illinois, the first of four sons of Effie Ann Vinson-Heller and John Barrow. John and Effie met in Ohio after the Civil War, and the young couple decided to head west for the greener land-grant pastures of Nebraska; Edward’s birth came during that arduous journey. A baseball enthusiast as well, Barrow pitched on a town team, but his playing career quickly ended when he critically injured his arm pitching in a cold rain. His baseball spirit remained intact, however, and he soon organized and promoted his own town teams. After accepting a more senior position at a newspaper, Barrow discovered future Hall of Fame outfielder Fred Clarke among his newsboys and recruited him for his ballclub. After a brief foray into the sale of cleaning products and time as a hotel clerk, in 1895 Barrow returned to baseball when he bought into the Wheeling franchise in the Inter-State League. At mid-season when the league collapsed Barrow moved his franchise into the Iron & Oil League. Baseball management now in his blood, Barrow acquired (with a partner) the Paterson, New Jersey franchise in the Atlantic League for 1896. Just after his acquisition of the Paterson club, Barrow signed the player he would later call the greatest of all-time, Honus Wagner. The following year, Barrow sold Wagner to the major league Louisville club for $2,100, a high price for the time. The contentious Atlantic League elected Barrow as president for 1897, and for the next three years until the league folded after the 1899 season, Barrow oversaw the inter-owner squabbles, dealt with numerous player disputes, and managed the umpires. As league president during the Spanish-American War, he championed a number of marketing gimmicks to help keep the fan's interest: he brought in a woman, Lizzie Stroud (she played under last name Arlington) to pitch and heavyweight champions John L. Sullivan and James Jeffries to umpire. Another heavyweight, Jim Corbett, often played first base in exhibitions, mostly in 1897. For 1900, Barrow purchased a one-quarter interest in the Toronto franchise in the Eastern League and became its manager. With little inherited talent, Barrow brought the club home fifth in his first year. Barrow acquired some better players for the next season, including hurler Nick Altrock, and finished second. Despite losing a number of players to the fledgling American League, Barrow's club captured the pennant in 1902. With the tragic suicide of new skipper Win Mercer in January 1903, Detroit Tigers owner Sam Angus hired Barrow as manager on the recommendation of AL president Ban Johnson. Bolstered by two contract jumpers from the NL, pitcher Bill Donovan and outfielder Sam Crawford, Barrow brought the team in fifth, a 13-game improvement over the previous year. After the season, Angus sold the franchise to William Yawkey after first offering it to Barrow and Frank Navin. The latter, soon promoted to secretary-treasurer, ingratiated himself with Yawkey, becoming his right-hand man. Barrow continued his effort to improve the club by adding several players that would contribute to the Tigers pennant four years later. Not surprisingly, however, Navin and Barrow, both young and ambitious, could not co-exist; with the Tigers at 32-46 Navin gladly accepted Barrow's resignation. Following his stint in Detroit, Barrow began a two-year odyssey managing in the high minors. Montreal, in the Eastern League, recruited Barrow right after his resignation to come finish out the 1904 season as their manager. For 1905 he was hired by Indianapolis in the American Association, and 1906 found him back in Toronto. Disheartened with his baseball career after his first-ever last-place finish that year, Barrow left baseball to run Toronto's Windsor Hotel. Four years later in 1910, Montreal offered Barrow the manager's post and a chance to get back into baseball. Barrow happily accepted, and after the season he was elected league president. In recognition of the two Canadian franchises, Barrow persuaded the Eastern League to change its name to the International League (IL) prior to the 1912 season. When the Federal League (FL) challenged Organized Baseball as a self-declared major league in 1914, the most severe hardship fell upon the high minors, particularly Barrow's IL, which lost numerous players to the upstart league. The FL also placed teams in the IL's two largest markets, Buffalo and Baltimore, significantly affecting attendance. To better position the IL for the struggle, Barrow tried to obtain major league status for his league or some eight-team amalgamation of the IL and the other affected high minor league, the American Association. Not surprisingly, nothing ever came of these efforts. With the collapse of the FL after 1915, the IL received a brief respite in 1916. In 1917, however, America also entered the First World War, bringing financial hardship back to many of the beleaguered franchises. Barrow again battled to keep his league from folding, while at the same time striving to create a third major league of four IL and four AA franchises. After four extremely difficult years, a number of disagreements and bad feelings had developed between the authoritarian Barrow and several franchise owners, particularly those left out of the third major league scheme. When the owners voted to drastically cut his salary from $7,500 to $2,500, Barrow resigned. For 1918, he eagerly accepted the Boston Red Sox managerial post offered by owner Harry Frazee. The Red Sox were less affected by war losses than most teams, and Barrow successfully guided the club to the pennant despite a showdown with his star player Babe Ruth in July. Earlier in the year, on the advice of outfielder Harry Hooper, Barrow had shifted Ruth to the outfield to take full advantage of his offensive potential. But when hurler Dutch Leonard left the team due to the war, Barrow looked to Ruth to pitch. Ruth begged off due to a sore wrist. The tension between the two erupted in July when Barrow chastised Ruth after swinging at a pitch after being given the take sign. When Ruth snapped back, the argument escalated, and Ruth left the club and returned to Baltimore, threatening to join a shipbuilding team. Ruth of course soon realized he'd gone too far and wanted to come back. Hooper and Frazee helped mediate and appease the furious, stubborn Barrow. The chastened Ruth ended up pitching a number of games down the stretch. Owing to complications from the war, in mid-year the season was shortened and adjusted to end on Labor Day, at which point the Sox found themselves 2 1/2 games ahead of the Cleveland Indians. In the World Series, the Red Sox defeated the Chicago Cubs, four games to two. Falling attendance and much lower receipts than anticipated from the World Series put additional financial burdens on Frazee. He now became a seller rather than buyer and sent three players to the Yankees for $25,000 prior to the 1919 season. During the year, Barrow became embroiled in two player controversies. The Babe spent the start of the season living the high life in Ruthian fashion beyond even his own standard. One morning on a tip, Barrow burst into Ruth's room at 6 a.m. right after the latter had snuck back in and caught Ruth hiding under the covers with his clothes on. The next morning in the clubhouse, Ruth confronted and threatened to punch Barrow for popping into his room. Barrow, well tired of Ruth's shenanigans, ordered the rest of the players onto the field and challenged Ruth to back up his threat. Ruth backed down, put on his uniform, and trotted out with the others. Barrow and Ruth eventually reached an unconventional detente: Ruth would leave a note for Barrow any time he returned past curfew with the exact time he came in. The other hullabaloo began when star Boston pitcher Carl Mays refused to retake the mound after a throw by catcher Wally Schang to catch a base stealer grazed Mays' head. Barrow intended to suspend the dour Mays, until Frazee quickly quashed any suspension so as to possibly trade him. After listening to several offers, Frazee sold Mays to the Yankees for $40,000. AL President Johnson voided the sale and suspended Mays, arguing Frazee should have suspended him. The Yankee owners went to the courts, which upheld the sale. Boston finished the 1919 season tied for fifth, 20 1/2 games back. That off-season, when Frazee sold Ruth to the Yankees, Barrow grimly told him, “You ought to know you’re making a mistake.” Frazee tried to placate Barrow by promising him that he would get some players in return for Ruth, but Barrow snapped back, “There is nobody on that ball club that I want. This has to be a straight cash deal, and you’ll have to announce it that way.” Yankee owners Jacob Ruppert and Tillinghast L'Hommedieu Huston paid $100,000 and Ruppert agreed to personally lend Frazee $300,000 to be secured by a mortgage on Fenway Park. Frazee desperately needed the money. When Frazee purchased the Red Sox in 1916, he and his partner paid Joseph Lannin $400,000 down and assumed $600,000 in debt and preferred stock, including a $262,000 note from Lannin. With the Federal League war over, Frazee assumed he could pay the interest and principal out of the team's cash flow. Attendance, though, collapsed in 1917 and 1918, and Frazee could not afford to carry both his ball club and his theater productions. By the end of 1919, Frazee's financial situation had become particularly acute. The principal on Lannin's note was due, and Frazee was in the process of purchasing a theater in New York (the sale price of the theater is unavailable, but it cost $500,000 to build). Shortly after the Ruth sale, Frazee pleaded with the Yankee owners to help him borrow against the three $25,000 notes because he needed the money immediately. He further implored Ruppert to advance the funds from the promised mortgage loan quickly. With the money from the Ruth sale Frazee could meet his immediate financial obligations but showed little interest in reinvesting in his ball club. The death of Yankee business manager Harry Sparrow during the 1920 season created an opportunity for the two sparing Yankee owners to bring in a strong experienced baseball man to run the team and thus help alleviate the friction between them. After a third-place Yankee finish in 1920, Huston and Ruppert plucked Barrow from Boston to run the baseball operation, technically as business manager, but practically in a de facto general manager-type role. While not technically a promotion, Barrow must have been relieved to escape a deteriorating situation in Boston to join well-capitalized, competitive owners. Forceful and competitive, yet optimistic by nature, Barrow actively sought to solidify his new club. At first this mainly involved going back to his old boss Frazee with Ruppert's money and acquiring the rest of Boston's stars. Yankee co-owner Ruppert was willing to spend money to acquire players when many other owners were not, despite the threat to his livelihood as a brewer from Prohibition. With his owners' encouragement, Barrow spent more, and more wisely, to build the Yankee dynasty. Barrow officially retired in 1947 but remained fairly active in baseball. He participated in several ceremonial events and served on the Hall of Fame old-timers committee, the body responsible for inducting players passed over by the baseball writers or excluded from their purview. Barrow survived a heart attack during the 1943 World Series, but in December 1953 at age 85 Barrow passed away after several years at home in ill health, just three months after his election to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

|

|||||