|

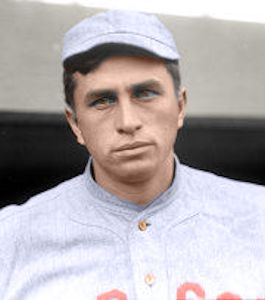

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||||

One of the best defensive right fielders in baseball history and one of the top leadoff hitters of the Deadball Era, Harry Hooper was also a team leader, superb practitioner of the inside game, and clutch hitter who played a key role in four Boston Red Sox world championships. As a product of rural California, but a college man who earned a degree in engineering, Hooper also symbolized baseball’s transition, ongoing during the Deadball Era, from a game rooted in the eastern cities and played by professionals who were largely uneducated and illiterate, to a game that broadened its geographical horizons and expanded its social appeal through players like Hooper. Although his play at times achieved the spectacular, Hooper eschewed flamboyance for simplicity, exaggeration for modesty. Possessing neither the crafted appeal of Christy Mathewson nor the raw excitement of Babe Ruth, Hooper practiced his profession quietly, skillfully, and confidently. More Everyman than Superman, he is a mirror of the game and its human touches in ways that his myth-encrusted contemporaries never can be. Though he never led the American League in any major statistical category, Hooper crafted a solid statistical resume that included 2,466 hits, 1,429 runs and 1,136 career walks, good for a lifetime .281 batting average and .368 on base percentage. In 92 career World Series at-bats, Hooper batted a solid .293; in the 1915 Fall Classic he batted .350 with two home runs. Hooper was considered the best defensive outfielder in the American League. Although the right field corner at Fenway Park was only 313 feet from home, the low fence that started at the corner merged with a higher wall and then headed toward a corner in right-center some 550 feet from home. There were odd angles at the bullpen and the joining of the two fences complicated plat for outfielders. Moreover, the tricky shadows and glare of the toughest sun field in the league, added to a rightfielder's adventures at Fenway Park. But nobody handled this better than Hooper. Hooper was the first man in the league to use flip-down sunglasses. He punched two holes in his cap for the string, which secure them under the bill of his cap. Harry claimed that he never lost a ball in the sun at Fenway Park and noone remembered otherwise. He also invented the sliding catch. He discovered he could best handle low line drives without losing his momentum or balance by sliding for the ball. He also retained complete freedom for his throwing arm and avoided any jarring contact with the ground that could knock a ball loose or cause an injury to his leg. He also thought sliding was a better way to stop grounders and always kept the play in front of him. But Harry's most lethal weapon was his arm. The power and accuracy of his throws was impressive and steady under pressure. He had the toughest throw to make in the Red Sox outfield because of the depth of Fenway's right field, which required him to make more long throws. He threw to all spots with amazing accuracy, and was able to throw strikes. Harry's outfield play earned him the respect of teammate and opponent alike. Harry Bartholomew Hooper was born on August 24, 1887 in California’s Santa Clara Valley, the fourth and youngest child of Joseph and Mary Katherine Keller Hooper. In 1876, Joseph had left Canada’s Prince Edward Island, slowly working his way westward through a series of jobs before landing in California. Growing up on the family ranch, Harry first honed his athletic skills by tossing fresh eggs against the side of the family’s barn. This merited little reaction from his parents, and Harry spent more time throwing various objects, challenging himself in distance and accuracy. His first formal exposure to nine-man-a-side baseball came during a trip East with his mother. While visiting her family in Central Pennsylvania, Harry watched with great interest the Lock Haven team play. He capped the trip with a visit to relatives living in New York City, and a chance to see his first Major League game. The Brooklyn Bridegrooms played the Louisville Colonels, and although the home team lost, Hooper’s dedication and love of the game solidified. Just before he and his mother began the long journey back to California, he received from his uncle something he later called “the best of all” his boyhood treasures: a bat, ball, and well-worn fielder’s glove. Harry Hooper’s formal baseball career began when he left the family’s farm in August, 1902, for the high school attached to Saint Mary’s College of California, then located in Oakland. Although Hooper originally arrived for a two-year secondary program, the Christian Brothers who ran the school quickly recognized his mathematical aptitude, and encouraged his parents to consider allowing him to complete the full baccalaureate program, which would stretch his time at the school from two years to five. Consistent with the emerging sense of education as a means to economic opportunity, Harry’s parents agreed to the school’s request. At roughly the same time, he earned a place on the secondary school’s new baseball team. Working his way up through the four teams at the school, Hooper earned a place as a starting pitcher on the junior varsity as a collegiate sophomore, but his stature—he stood slightly over five feet tall at the time—and pitching velocity limited his chance to earn a spot on the varsity squad. The top team’s head coach suggested a switch to an outfield position, which Hooper accepted. It assured him the starting left-field spot on the College’s varsity nine at the start of the 1907 season, a team regarded by many as one of collegiate baseball’s finest in the pre-World War I era. The team that completed a 27 game season with a perfect record. Among that year’s victims were Stanford University, the University of California, a Pacific Coast League all-star team, and the Chicago White Sox who the Phoenix faced in an exhibition game prior to the start of the major league season. Hitting for a .371 average during his senior season, Hooper drew the attention of several organized ball representatives, and signed his first contract—for 10 days—to play with the Alameda club of the California League, where he teamed with Duffy Lewis for the first time; the two had been schoolmates but not teammates at St. Mary’s. Ironically, the short length of the contract was Hooper’s idea. Focused primarily on his engineering career, he agreed to play only for the time between the end of the Phoenix’s season and his graduation date. His strong play during the short stretch earned Hooper a contract with the Sacramento club, which he agreed to accept with the proviso that Sacramento’s owner arrange a surveying position for him, which was done. Late in the 1908 season, after hitting .347, scoring 39 runs, and stealing 34 bases in 68 games, Hooper earned the tag, “Ty Cobb of the State League,” and an offer from his manager, Charlie Graham, who also served as a scout for the Boston Red Sox. Initially when approached about the possibility Hooper recalled saying he thought baseball “was a sideline to engineering to make enough money for a living.” Graham persisted and Hooper agreed to meet with Red Sox owner John Taylor, who soon would be in the area to observe several prospects for his team. At their meeting at a Sacramento saloon, the two agreed to a contract that would pay the 21-year-old Hooper $2,800 for the 1909 season, approximately $1,000 more than he would have made combined through his California baseball play and his job with the Western Pacific Railroad. Harry Hooper’s career with the Boston Red Sox began on March 4, 1909 when he arrived in Hot Springs, Arkansas for the team’s training camp. The Red Sox of 1909 represented a team in transition. Following the demise of the championship clubs of 1903 and 1904, owner Taylor aspired to build a pennant contender with young pitchers, power hitting, and speed on the bases. The rotation included Joe Wood, Eddie Cicotte, and Frank Arellanes. Other than Heinie Wagner (shortstop), no member of the squad had two complete seasons with the team. Harry Hooper’s major league debut came on April 16, in Washington, D.C., during the team’s second series of the season. Called upon to start in left field and bat seventh, Hooper lined a single in his first at-bat that also notched his first RBI. That day he went 2-for-3 at the plate, with “a clever steal in the ninth,” three flies caught including “a superb running back catch” that saved a triple, and one assist when he threw out Gabby Street at home. During the first month of the season, he played occasionally, always fielding well. A natural right-handed hitter and fielder while at Saint Mary’s, the 5’-10” 168-pound Hooper experimented with switch hitting. Playing in an era when manufacturing runs one at a time mattered more than sheer power, Hooper decided to take advantage of his abilities and reduce one step from the batter’s box to first base by making the move to full-time left-handed hitting. His hard work and dependable play, especially in the field, made personnel decisions easier for the club’s management. By the season’s midpoint, Hooper firmly held the fourth outfield position, and often entered games in the late innings because of his defensive skills. The squad finished the year in third place, 9˝ games behind Detroit, but also 25 games over .500. Hooper recorded a .282 average in 81 games, while completing the transition from one side of the plate to the other. The Red Sox that assembled in Hot Springs, Arkansas in March, 1910 had reason to be optimistic about the coming season. Most of the lineup returned, with Hooper virtually assured one outfield spot. With Tris Speaker secure in center, the only question was whether it would be right or left on a day-to-day basis. The arrival of another veteran of the Saint Mary’s Phoenix in camp, George “Duffy” Lewis, largely settled the issue. The outfield trio of Tris Speaker, Harry Hooper in right, and Duffy Lewis in left made its debut on April 27. Through the course of that season—when they hit a combined .296—and the next five, the “Million Dollar Outfield” played more than 90 percent of Boston’s games. After batting .267 in 1910, Hooper improved to an impressive .311 average in 1911, scored 93 runs, and posted a .399 on-base percentage. The club, however, failed to finish better than fourth in either season. Despite his .242 batting average, Hooper was an integral piece of the 1912 pennant-winners, ranking second on the team with 98 runs scored, 66 walks, 29 stolen bases, and 12 triples. In that year’s World Series against the New York Giants, Hooper elevated his play, batting .290 for the Series and making several crucial plays at bat and in the field. In Game One, Hooper rapped a game-tying double in the seventh inning to secure a 4-3 Boston victory. After taking a three-games-to-one lead in the Series, the Red Sox saw the Giants even things at three games each. There was one tie game. Despite numerous baserunners for both teams, the Giants held a slim 1-0 lead in the seventh inning of the deciding Game Eight, which would have been greater if not for Hooper’s catch of Larry Doyle’s drive to the right-field fence, robbing him of a home run. The game was tied 1-1 after nine. In the 10th inning, after Clyde Engle reached second when Fred Snodgrass muffed a fly ball, Hooper followed with “a sure triple” that Snodgrass caught, but it advanced Engle to third. After a walk to Yerkes, Speaker singled in Engle with the tying run. Yerkes took third on the play, Speaker took second on the throw home, and Larry Gardner's sacrifice fly won the World Series for the Red Sox. Hooper’s “paralyzing catch” in the final game earned him accolades in the press, but John McGraw paid an even higher compliment when he labeled the Californian, “one of the most dangerous hitters in a pinch the game has ever known.” In the next day’s Boston Globe, Speaker called Hooper’s catch “the greatest, I believe, that I ever saw.” Coming off the championship year, Hooper remained dedicated to his off-season training. Although the Red Sox struggled as a team in 1913 and 1914, Hooper personally improved his offensive output, hitting .288 in 1913 and scoring 100 runs, and batting .258 with 85 runs scored in 1914. On May 30, 1913, Hooper hit home runs to lead off both games of a double-header, a feat not equaled until Rickey Henderson did it 80 years later. In 1915 the Red Sox returned to championship form and began a stretch of success where the team played the best, and most consistent, baseball in the major leagues. Between 1915 and 1917, the team won at least 90 games each season, and likely would have done so again in 1918 if World War I had not shortened the season. The successes came through the team’s effective use of the strategies of the era. Rather than power hitting and home runs, the Red Sox won by manufacturing runs, playing strong defense, and, most of all, getting solid pitching. In fact, during the four-year stretch, the team never featured more than one hitter with an average of .300 or higher. In 1915, Hooper’s average dipped to .235, but he compensated by collecting 89 walks, fifth best in the league, and posting a respectable .342 on-base percentage. Once again, he saved his best work for the World Series, when he helped Boston finish off Philadelphia in five games with a .350 batting average and two home runs, both of which came in the final game of the Series, making Hooper only the second player in World Series history to homer twice in the same game. (Both homers bounced into Baker Bowl’s temporary stands; today they would be considered ground-rule doubles.) After another championship in 1916, and a disappointing second-place finish nine games behind the Chicago White Sox the following year, Hooper’s Red Sox entered the 1918 season in a tenuous position. Although Boston’s roster suffered fewer losses to the military and war-related industries than other teams, the lineup managed a woeful team average of .249, the second-worst in the American League; Hooper posted a .289 average and a .405 slugging percentage (second on the team to Babe Ruth in both categories). He also helped the team to another pennant in a war-shortened season (126 games) that ended with a dramatic labor challenge during the World Series. During the Fall Classic against the Chicago Cubs, Hooper demonstrated his clear thinking and effective leadership, representing his fellow players’ concerns in a manner that preserved the integrity of baseball, while also exposing some of the inherent weaknesses of baseball’s ruling system. Due to wartime travel restrictions, the teams played the Series in a 3-4 format, with the first games in Chicago (ironically at Comiskey Park). The rest of the games took place at Fenway. The Red Sox returned home enjoying a 2-1 lead, but all was not well. For several war-related reasons, attendance and gate receipts during the regular season and World Series in 1918 fell well below pre-war levels. However, at this time the players’ postseason bonuses came from gate receipts and the owners would not guarantee a minimum payment. The two teams, traveling on the same train, appointed four representatives, including Hooper, to speak to the governing National Commission and press their case. With Boston leading three games to one, the players delayed the start of the fifth game by more than one hour in an attempt to secure concessions from the Commission. Although Hooper negotiated an end to the strike, and secured a verbal promise from Ban Johnson of no reprisals, he forever regretted not securing the guarantee in writing. After Boston won the Series 4-2, its last for 86 years, the players received the smallest financial awards in World Series history. After a .312 season in 1920, Harry Hooper’s career with the Boston Red Sox ended on March 4, 1921, when Boston owner Harry Frazee thwarted a holdout by trading him to the Chicago White Sox for Shano Collins and Nemo Liebold. Hooper posted some of the best offensive seasons of his career during his five years with the White Sox. In 1921 he batted .327; the following year he notched career highs in runs scored (111), home runs (11) and RBIs (80). In 1924, he posted a career-best .328 batting average and .413 on-base percentage. In 1925, his last major league season, Hooper batted .265. Playing in his final major league game on October 4, 1925, Hooper went 1-for-4 with a double. Upon his retirement, Hooper served as postmaster of Capitola for over 20 years. His greatest honor came in 1971, when the Veteran’s Committee elected him to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

|

|||||