|

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||

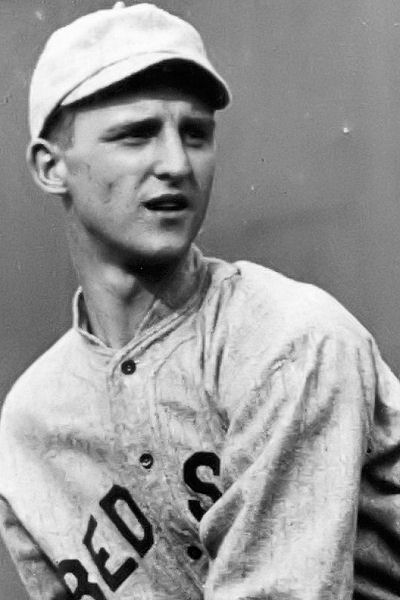

Herbert Pennock was born February 10, 1894, in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania. He was the fourth and last child of Theodore Pennock and the former Mary Louise Sharp, were of Scots-Irish ancestry with Quaker roots going back to William Penn. In 1909 for the local Friends' School and then the Cedarcroft Boarding School, Pennock was a weak-hitting first baseman cursed with a frail arm that curved everything he threw. His Cedarcroft coach, acting on the advice of team first baseman Albert Aloe, who insisted that Pennock was a natural pitcher, placed Pennock on the mound one day when the team's regular pitcher failed to show. Reportedly, Pennock struck out nineteen. Pennock began dominating as a pitcher and at the age of seventeen got a call from Connie Mack. Mack, manager of the World Champion Philadelphia A's, placed him with his Atlantic City Collegian team in the Seashore League for $100 a month. Pennock's father demanded Pennock protect his college eligibility and only let his son sign under an alias. When Pennock no-hit the St. Louis Stars, a respected traveling black team, Mack promised a 1912 call-up. While Herb was pitching for the Wenonah, New Jersey, Military Academy that spring, Mack offered Pennock a spot on his bench. Pennock accepted and on his second day at the park made his debut against the White Sox, Tuesday, May 14. He gave up one hit in four innings. The A's of this period, three-time World Champions, deserved their reputation as the smartest team of their generation. As a coveted apprentice of Mack's, Pennock learned from Chief Bender, who taught him the screwball, and ex-major league catcher Mike Grady, a Kennett Square neighbor who made Pennock his personal project. Pennock was ill at home in Kennett Square for most of 1913 but ended 1914 with five straight wins and three scoreless innings in the World Series. When Mack let his superstars go in 1915, Pennock became the ace of one of the most misguided youth movements in baseball history. Then on May 23, in Detroit, Pennock allowed two hits and two walks in the first inning throwing with his usual nonchalance. A panic-stricken Mack, still convinced that the A¹s were a great team, concluded Pennock "lacked ambition," yanked him from the mound, and summarily released him as a scapegoat. Boston, against whom Pennock had nearly thrown a no-hitter, eagerly scooped him up at the waiver price. Until he died, Mack referred to the release of Herb Pennock as his greatest mistake. In Boston Pennock was the seventh pitcher on a staff seven-deep and did not see much action. Loaned to Providence at the end of 1915, and then to Buffalo at the end of 1916, Pennock went 11-9 in twenty-two International League starts. In 1917, Pennock won three straight starts for Boston, including a Fourth of July win over the A's that helped the Red Sox tie Chicago for first place July 6. But with the pennant race nip-and-tuck manager Jack Barry kept Pennock on the bench the rest of the year. Frustrated by six partial seasons, Pennock joined the Navy in 1918, and actually steered clear of the Navy baseball team until dispatched to Gibraltar in late June. Navy officials, gearing up for a game against the Army in the 40,000-seat Chelsea Stadium, found out Pennock was mid-Atlantic and had the ship diverted to Portsmouth so he could pitch. He beat the Army in ten innings, 2-1, in front of the King of England on the Fourth of July. When Ed Barrow sent him a Boston contract after the war, Pennock held out until Barrow promised to use him regularly. Pennock started once in April and once in May 1919, while the team was giving George Dumont, Bill James, and sore-armed Joe Bush a chance. In late May, Pennock reminded Barrow of his promise to use him regularly and threatened to quit the team. On Memorial Day in Philadelphia, Pennock started and did well in a no-decision. Then on June 6, Pennock was given another chance and pitched a six-hit, 3-1 victory over Detroit, also getting the game winning hit in the seventh inning to bump Boston into the first division. With continued regular work he posted a 14-4 record after the Fourth of July. Over the next three seasons Pennock was a .470 pitcher on a .450 team as Boston's championship franchise faded away. On May 1, 1920, he gave up a home run to Babe Ruth, an old Boston buddy of his whom he often helped read fan mail. It was Ruth's first home run as a Yankee. Pennock gained a reputation for needing four days of rest between starts. He could win if called on to pitch sooner, but in subsequent starts his curveball lost its fine edge. Boston's ace only in 1920, Pennock was more commonly the team's third starter. Yet even in 1920 the Boston Herald said, "Pennock does give the impression that he is a little on the don-care order." Furthermore, the "August breakdown" was becoming a Pennock specialty. His career record for the first ten days of August was 8-17. Pennock was traded to the Yankees on January 30, 1923, for Camp Skinner, Norm McMillan, George Murray and fifty thousand Broadway-bound dollars. He came into his own at Yankee Stadium. Pennock may have been the greatest "non-ace" in baseball history and soon developed a reputation of winning "the big game." He also showed off an encyclopedic knowledge of the weaknesses of opposing hitters, a habit gained from the bench of the old A's. In his first year with New York he went 19-6, leading the league in winning percentage and helping the Yankees to their first world's championship. In his first six seasons with New York his average record was 19-9, helping New York to three straight pennants in 1926, 1927 and 1928. At the age of thirty-five Pennock did not return to peak form. He hung on as a fifth or sixth starter until 1932 and then moved to the bullpen. He struggled through his 1929 comeback with eleven, appropriately, as his newly issued uniform number and became the third left-hander in major league history to win 200 games. Pennock's gracious manner and taste were old-fashioned to the extreme, yet to describe him as a man was to speak of contrasts.Cool and impossible to fluster on the mound, Pennock was intense and introverted in the clubhouse before a start. He was a Quaker who wore thousand-dollar rings; a ballplayer who led fox hunts in the off-season. His family was independently wealthy from the sale of their road and farm equipment business late in the nineteenth century, yet he never hesitated to stretch out contract negotiations and became one of the highest paid players in the mid-twenties with a salary just over twenty thousand dollars a season. He invested his first New York World Series bonus in a fox pelt farm in New Brunswick (which he moved to Longwood, Pennsylvania in 1925), built chrysanthemum greenhouses on his Kennett Square property, and collected antique furniture. These hobbies, so unique for a ballplayer, along with the fact that he never swore and never drank, gave him the appearance of royalty. His nickname, The Squire of Kennett Square, summed up his persona. Posthumously he was more often referred to as The Knight of Kennett Square. Yankee manager Joe McCarthy allowed Pennock to "pick his own spots" in his final years as his career waned. New York released Pennock on January 6 after a testimonial dinner. Pennock had developed a lifelong friendship with Eddie Collins while on the A's, and when Collins became general manager of the Red Sox he brought Pennock over for one more season in 1934. This was the year Fenway got a new generation of star players and its modern green-paint look. It was a joyous farewell season for Pennock. Fenway Park was crammed with 44,631 Boston fans on April 22, but the Yanks beat the Sox, 8-1. Pennock's appearance in the ninth inning was the highlight as Ruth and Gehrig were due up. In a circus-like atmosphere, he allowed back-to-back doubles. On June 1, with Lefty Grove scheduled to start, the Red Sox scored nine runs in the top of the first inning at Washington and Pennock (who had batted in the top of the first) was put on the mound. He finished with a complete game, nine-hitter, his final career win, by a score of 13-1. He logged innings as a reliever in out-of-reach losses throughout the summer and was given one last start, August 27, against Cleveland before the team went on its last road trip. Pennock always had bad luck against Cleveland, so much so that Miller Huggins often avoided pitching him against them. In his final major league appearance the best Pennock could do was a no-decision against Lloyd Brown. Pennock retired to his horses and silver fox furriery at Kennett Square in 1935 when new Red Sox manager Joe Cronin brought along his Washington coaching staff. From 1936 to 1938 he was Boston's first base coach and pitching coach and moved to Assistant Supervisor of Boston farm teams under ex-umpire Billy Evans for 1939. Late in 1940 he replaced Evans as Director of Minor League Operations for the Red Sox. In December of 1943 Bob Carpenter bought the Phillies and sought the advice of Connie Mack in picking a general manager. Here Mack made amends to the left-hander he once released and recommended Pennock. Carpenter and Pennock hit it off; Pennock was hired "for life" and given a big, sun-filled, corner office on the 19th floor of the Packard Building in Philadelphia. When Carpenter was drafted into World War II in 1944, Pennock temporarily filled the offices of President and GM. Pennock spent over a million dollars on players that would make up most of the pennant- winning 1950 Whiz Kids. But he never saw them play. Attending a league meeting in New York on January 30, 1948, Pennock collapsed into Carpenter's arms after passing through the revolving doors to the lobby of the Waldorf-Astoria hotel. He died two hours later of a stroke at the age of 53. Emotion carried over into Hall of Fame elections that year. Pennock was elected to the International League Hall of Fame in February and to Cooperstown with 82 percent of the vote despite weak Cooperstown election showings dating back to 1937.

|

|||