|

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||||

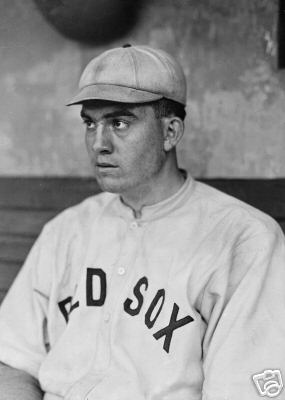

Ray Collins might have been on his way to the Hall of Fame but for an abrupt and mysterious end to his career after only seven seasons. In 1913-14 he won a combined 39 games for the Red Sox, and his lifetime 2.51 ERA is impressive even for his low-scoring era. Collins was a good hitting pitcher and an outstanding fielder, but the key to his success was his remarkable control. He consistently ranked among the league leaders in fewest walks allowed per nine innings, finishing third in the American League in 1912 (1.90), second in 1913 (1.35), and fourth in 1914 (1.85). Though big for his time (6-feet-1, 185 pounds), the Colchester farmboy did not throw hard. Ray received offers from eight of the 16 major-league teams. He decided to follow in Gardner’s footsteps and went down to Boston and came to terms with Red Sox president John Taylor. On July 19, 1909 with the Red Sox down 4-0 to Cy Young after three innings at Cleveland, Boston manager Fred Lake figured it was as good a time as any to test out his acclaimed rookie. In five strong innings of relief, Ray yielded two unearned runs and even singled in his first big-league at-bat. This game is best remembered as the one in which Cleveland shortstop Neal Ball made the first unassisted triple play in major-league history. Four days later, on the 23rd, Ray was the starting pitcher against the hard-hitting Detroit Tigers. Though he lost 4-2, he twice struck out the dangerous Ty Cobb. Collins was given a second chance to beat the Tigers on July 25, 1909. Pitching on only one day’s rest, Ray tossed the first of his 19 shutouts in the majors. It was a three-hitter, and all three of the hits were made by Hall of Famer Sam Crawford. Collins pitched only sporadically during the rest of the 1909 season, going 4-3 with an ERA of 2.81, but he had proved that he was capable of competing in the majors without any minor-league apprenticeship. As if to prove the point, after the regular season Ray matched up against the great Christy Mathewson on October 13 and defeated him, 2-0, in an exhibition game against the New York Giants. Collins became a regular in the Boston rotation in 1910. In his first full season in the majors, the 23-year-old pitched a one-hitter against the Chicago White Sox and compiled a 13-11 record, making him the second-winningest pitcher on the Red Sox. His ERA of 1.62 was sixth best in the American League. He became a fan favorite at the Huntington Avenue Grounds. He was 3-6 at one point in the 1911 season, prompting rumors that he was soon to be released. Ray was noticeably overweight when he reported for spring training at Hot Springs, Arkansas in 1912, and his problems were compounded when a spike wound resulted in an abscess on his knee. Collins missed the first two months of the 1912 season, during which time the Red Sox christened their new stadium, Fenway Park. Ray did not start a game until June 7, nor win one until June 22, but from that point on he was nearly invincible. A half-century later, Ray’s fondest memory of that season was pitching the first-place Red Sox to two victories in three days over the second-place Athletics at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park. When he defeated the A’s 7-2 on July 3, the headline in the next day’s paper, over Ray’s photograph, read, “SURPRISED ATHLETICS, RED SOX AND PROBABLY HIMSELF.” Then on July 5 he surprised the A’s again, 5-3. Collins finished fifth in the American League in shutouts in 1912, but all four of them came in the second half of the season. By October his record stood at 13-8 and his ERA at 2.53, fifth-best in the American League. The team’s only left-hander, Collins was considered the second best pitcher on the staff behind Smoky Joe Wood (34-5) as the Red Sox walked away with the American League pennant. Ray started Game Two of the World Series against New York Giants ace Christy Mathewson and led 4-2 after seven innings. Then in the eighth Collins was pulled with only one out after the Giants rallied for three runs. The game was called on account of darkness after 11 innings with the score tied 6-6 (which is why the Series went eight games). The Red Sox led the Series three games to one by the time it was Collins’s turn to pitch again in Game Six, but player-manager Jake Stahl surprised everyone by starting fireballer Buck O'Brien. O’Brien was no slouch, coming off a 20-13 season, but the Giants shelled him for five runs in the first inning. Collins took over in the second and pitched shutout ball for seven innings, but the Red Sox lost 5-2. Game Six turned out to be Ray’s last appearance in a World Series, and though he ended up with no decisions, he did not walk a single batter in 14 innings – quite possibly a World Series record. Collins had his best season yet in 1913, finishing at 19-8, his .714 winning percentage the second-highest in the A.L. A highlight was his performance on July 9, when he pitched a four-hitter and hit a home run in a 9-0 drubbing of the St. Louis Browns. Another characteristic outing was July 26 against the Chicago White Sox, when Collins pitched a five-hitter and hit a bases-loaded triple to give Boston a 4-1 victory. On August 29 Collins pitched scoreless ball for 11 innings to defeat Walter Johnson, who entered with a 14-game winning streak. It was one of three times that Ray went head-to-head against the Big Train in 1913; each game was decided by a score of 1-0, with the Vermonter winning two of them. Coming off a fine season in 1913, Ray Collins expected his $3,600 salary to increase substantially for the 1914 season, and was sorely disappointed when the contract the Red Sox sent out on January 16 called for only $4,500. On January 23 he returned it unsigned to new Red Sox owner Joseph Lannin. In a typical year Collins would have had no choice but to accept Lannin’s terms, but 1914 was no typical year. That winter the Federal League was waging its war for baseball supremacy; players had options for the first time in years. Collins did report to Hot Springs. Newspapers reported that the Federal League had offered Collins a three-year contract at $5,000 per year, with a signing bonus of $7,500, and that he was slated to pitch for the Brooklyn Tip-Tops. That same day Lannin arrived at Hot Springs, issuing a proclamation that Collins had 24 hours to sign with Boston or leave the team. Ray met with Lannin and Bill Carrigan for an hour before dinner, and when they emerged they announced that Ray had signed a two-year contract. Though he refused to disclose exact terms, one Boston paper was probably correct in reporting that the contract called for $5,400 per year. Ray’s signing was a tough blow for the Federal League. With the illness of Smoky Joe Wood, the Red Sox expected Ray Collins to step up and become the ace of their pitching staff in 1914, and that is exactly what he did. His six shutouts ranked fourth in the American League that season, and he was one of only three A.L. pitchers to reach the 20-win plateau. He picked up his 19th and 20th victories on September 22, 1914, by pitching complete games in both ends of a doubleheader at Detroit’s Navin Field. Collins won the first game, 5-3, and the nightcap, 5-0. In 1915, because the Boston Red Sox were in the enviable position of having too many good pitchers, Collins was relegated to the bullpen. As early as June, newspapers began speculating that he was soon to retire; one even printed a false rumor that he had purchased a hotel in Rutland. Starting only nine games, the fewest since his rookie year, Ray finished at 4-7 with an abysmal 4.30 ERA. Collins did not pitch a single inning in the 1915 World Series as Boston defeated the Philadelphia Phillies four games to one. After the season the Red Sox expected him to take a cut in pay to $3,500. Rather than suffer that humiliation, on January 3, 1916, Collins announced his retirement from professional baseball, stating simply that he was “discouraged by his failure to show old-time form.” He was only 29 years old.

|

|||||