|

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||||

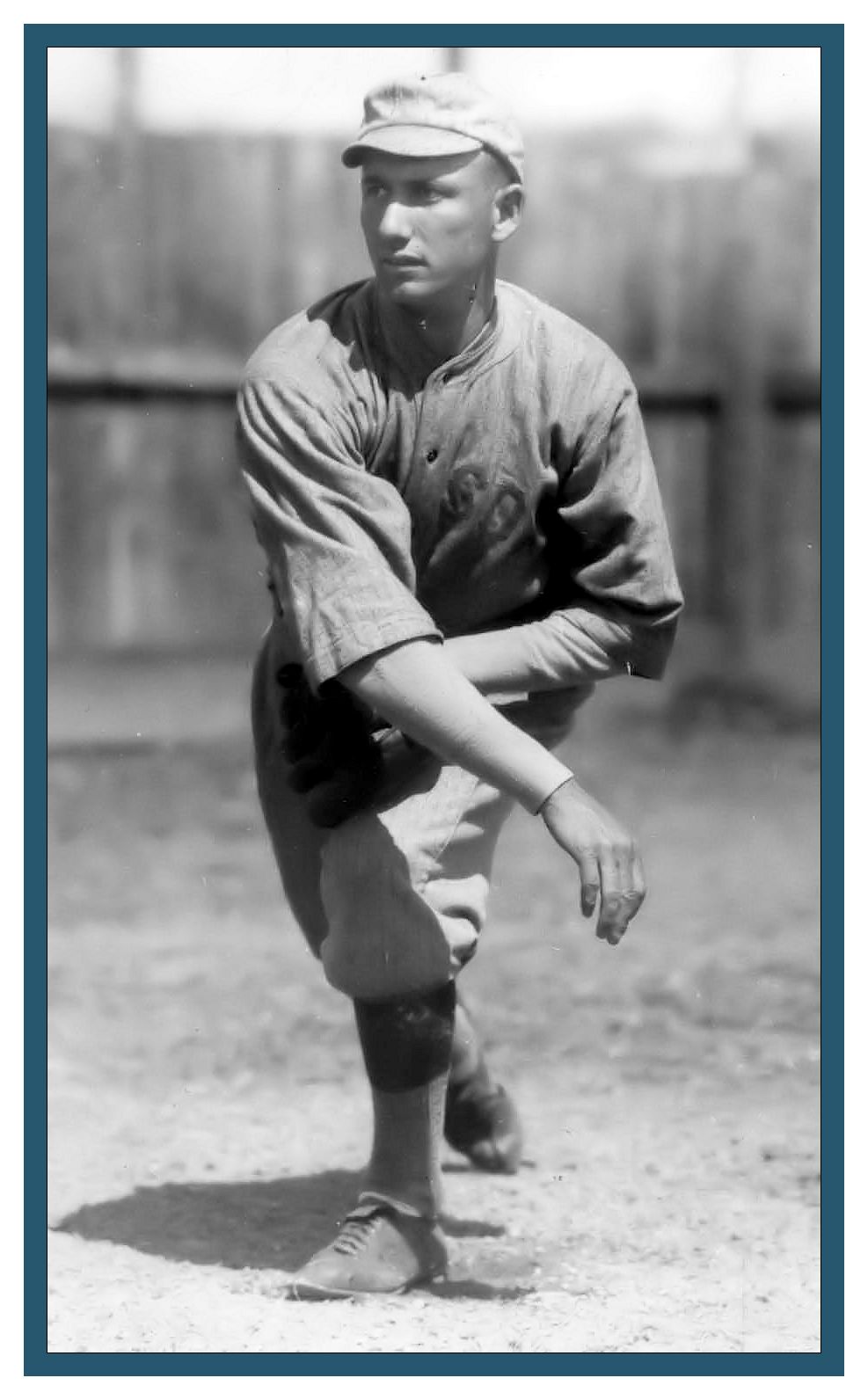

For a player so significant in Red Sox history, surprisingly little is known about Samuel Pond "Sad Sam" Jones. Despite his incredible contributions to the Red Sox World Series victory in 1918, the most often discussed thing about Jones is his curious nickname. Born July 26, 1892, in Woodsfield, Ohio, about 20 miles west of the West Virginia Panhandle, Sam developed his arm on his grandfather's farm by throwing potatoes across a field to his brother Robert. He pitched well in high school, but quit ball to take a full-time job at Schumacher's grocery store. Though he intimated to family that he preferred basketball, and would have played it professionally had there been a league at the time, he kept pitching in pickup games, and in 1913, he was asked to try out for Zanesville of the Inter-State League. That was where he first broke into professional baseball, winning two games and losing seven but also getting good experience including pitching in a June exhibition game against the New York Giants. During the offseason, Jones played semipro basketball, a sport he claimed to be better at than baseball, but in the spring of 1914, he returned to baseball, spending some time at the Bill Doyle baseball school in Portsmouth, Ohio. Later that summer, Jones left the school to sign with the Portsmouth team in the Ohio State League, where he posted a losing record (5-6) but showed some potential when it mattered. One day, with Cleveland Indians scout Bill Reedy watching the game, Jones pitched well enough to earn a victory and hit a triple and home run to help his own cause. Reedy was impressed and signed Jones for the Indians later that year. He spent most of the year pitching for Cleveland's American Association team (10-4 in 23 games, with a 2.44 ERA), earning a promotion to the big-league club for one game in the middle of the year. Jones debuted with the Indians on June 13, 1914. In 1915 he became a regular his first of 21 seasons pitching for six of the eight American League clubs. In his only full year with the Indians, Jones was 4-9 (3.65 ERA) and walked more (63) than he struck out (42). Jones batted .156 for the Indians. On April 12, 1916, the Indians traded Jones to the Red Sox with Fred Thomas and $55,000 for future Hall of Famer Tris Speaker. The Joseph Lannin-owned Red Sox were dumping Speaker and his high salary, to the distress of Red Sox fans. Thomas was the man Lannin wanted; Jones himself was an afterthought at best. The 1916 pitching staff was essentially the same one that had won the 1915 World Series; Vean Gregg who got most of the work the sore-armed Smoky Joe Wood had previously handled, while Jones threw only 27 innings, all in relief, losing his only decision. Jones was used even less in 1917, reprising his 0-1 record. The loss came in his only start of the year, in Cleveland on August 19. He was hammered for two runs in the first and two in the fourth. At the start of his tenure with the Red Sox, Jones hardly seemed a big part of the ballclub. The Boston Herald and Journal reported that Jones wasn't even sent a contract in 1918. The team was at Hot Springs when owner Harry Frazee got a letter from Sam along these lines: 'Forgotten me altogether? I'm not worth a contract of any sort? If I am through, let me in on it.' " Red Sox executives told the Globe that they thought he was at Camp Sherman in the Army and had placed him on the voluntarily retired list in error. They wired Jones to come quickly, and told the newspaper they expected him to get a fair amount of work. Fortunately for Jones, the Red Sox were right. The new manager for 1918, Ed Barrow, saw that Jones had a "most baffling delivery" and nurtured him into a pitcher who delivered 16 victories against only five losses (2.25 ERA). Though Barrow would later say that he was equally as proud of turning Babe Ruth into an outfielder as he was of turning Jones into a great pitcher, Jones and his manager had a contentious relationship at best. On May 23, 1918, Jones had his first start of the season and pitched extremely well against Cleveland--though he was on the short end of a 1-0 decision. Jones's next two starts were brilliant. He outpitched Walter Johnson, his childhood hero, on May 29, winning a 3-0, five-hit shutout, and followed that with a 1-0 shutout of Cleveland on June 6, again allowing just five hits, but this time in 10 innings. After allowing just one run in three starts, Sam Jones had cemented himself in as part of the starting rotation. In the first 29 innings he threw against his former ballclub, Jones allowed Cleveland just one run. It seemed to take him a while to harness his pitches (he walked more than he struck out in each of his first five full seasons in the majors), but Jones maintained that during a five-year stretch he only once threw over to first base to hold back a runner, believing that "there are only so many throws in an arm," something future Hall of Famer Eddie Plank had told him. When Ernie Shore left for the Navy, Dutch Leonard took a shipyard job, and Babe Ruth cut back a bit on pitching, Joe Bush and Sam Jones got the opportunity to pitch in 1918. Bush won 15, Jones won 16, and Carl Mays won 21. It was a terrific year, and Jones led the league in winning percentage as the Red Sox advanced to the World Series. Though Jones lost his start in Game Five, 3-0, the Sox won the Series--it would be their last world championship for 86 years. The next year, 1919, wasn't as kind to Jones as 1918, and Sad Sam finished the season 12-20 with an inflated 3.75 ERA. The team itself had a losing record, and several headlines mentioned Jones' wildness and wobbling. Jones got more work than anyone else on the staff, but others pitched better. He did dominate Washington, throwing three shutouts in a row before losing in the last matchup. In 1920, Jones's workload increased to 274 innings but he again had a losing record (13-16, with an ERA that grew to 3.94.) He often pitched very well indeed, but was inconsistent and also often suffered from poor run support, though he perhaps single-handedly denied the pennant to the White Sox. Chicago finished two games behind the Indians, and Jones beat them six times. Only once in the first five of those wins did Jones give up as many as two runs. There were, though, the losses: On June 12, he gave up six runs to the St. Louis Browns in the first inning, left the game, and lost. Trying again the very next day, he was left in to pitch the full game and lost again, 11-5. It took until 1921 for Jones to turn it around again. Even though the team again had a losing record (as it did throughout the 1920s), Jones became a 20-game winner (23-16, 3.22 ERA), making himself an attractive target for the acquisitive New York Yankees. Five days before Christmas 1921, Harry Frazee traded Jones, and Bullet Joe Bush (between them, the two pitchers had accounted for 39 of Boston's 75 wins in 1921) and threw in eight-year veteran Everett Scott, for four New York players: Roger Peckinpaugh, Rip Collins, Bill Piercy, and Jack Quinn. The three pitchers Frazee picked up each improved their win totals in 1922, and initially, the trade seemed like a very smart move. Sam was 13-13 with the Yankees his first year, but went to the World Series again. It was back to the Series again in 1923, Sam's 21-8 and Herb Pennock's 19-6 pacing the Yankees during the season. Jones entered 1924 with a sore right elbow that lasted two months and contributed to a disappointing 9-6 record. In 1925, he pitched a full year again but the Yankees collapsed all the way to seventh place. Jones spent five years pitching in New York, but it didn't change him as a man. Jones was, according to those who knew him, a homebody. He hated leaving his Woodsfield hometown for spring training, and minutes after the season, he would hustle his belongings, his wife, Edith, and their sons, George and Paul, into their LaSalle automobile and drive straight to Woodsfield. In early February 1927, Sam was swapped to the St. Louis Browns for Cedric Durst and Joe Giard. In his one season with St. Louis, Jones was 8-14 with a 4.32 ERA. Right after baseball wrapped up postseason play, St. Louis sent Sam and Milt Gaston to Washington for Dick Coffman and Earl McNeely. Sad Sam pitched four years for Washington, rebounding nicely with a 17-7 (2.84) in 1928. After a 9-9 year in 1928, his hopes for another strong season in 1929 were dashed when he sprained his back on May 22. Owner Clark Griffith signed him again for 1930, but to a "bonus contract" based on incentives. In 1931, Jones was 9-10, and in December the Senators traded him and Irving "Bump" Hadley to the White Sox for Carl Reynolds and Johnny Kerr. Sam Jones won 10 games for the White Sox in 1932 and again in 1933, but was under .500 each year. In 1934, he celebrated his 42nd birthday with a five-hit, 9-0 shutout of Washington. In November 1935, after he had posted a winning 8-7 record, the White Sox gave Sam Jones his unconditional release at age 43. His 22-year career was finally over. He kept busy, teaching kids in Woodsfield how to play ball. Sam spent four summers coaching the Woodsfield Junior Merchants. In 1939, a brief INS wire story reported on a "married men vs. single men" ballgame from the prior summer, in which a batter drove a liner back to the mound and broke Sam's finger. In December, he signed on as a coach-player with the International League Toronto Maple Leafs, where he worked under manager Tony Lazzeri, a former teammate with the Yankees. Jones' last season as a professional came in 1940, after four years out of the game. He appeared in eight games for the Maple Leafs, for a total of 12 innings, with a winning 1-0 record and a somewhat meaningless 2.25 ERA. Soon after his 48th birthday he was released by the Maple Leafs. In his final appearance, he'd thrown one inning without giving up a hit or a run. Two years later, he briefly dipped back into baseball when he was hired by a factory in Springfield, Vermont, to coach its team in the city league. His son Paul played for the team, and lived in Springfield after Sam had moved back to Woodsfield. In the years after baseball, Jones prospered in his hometown as president of the board of directors of the Woodsfield Savings and Loan Co., and was active in Presbyterian Church and Masonic circles. Sam suffered an illness that lingered and then took his life on July 20, 1966, just 20 days before his 50th wedding anniversary.

|

|||||