|

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||||

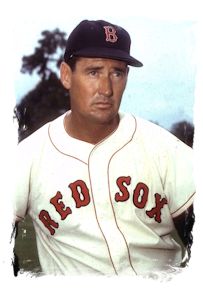

Any argument as to the greatest hitter of all time always involves Ted Williams. It’s an argument that can never be definitively answered, but that it always involves him says a lot. If the name of the game is getting on base, no one ranks above him. At age 20, he said, “All I want out of life is that when I walk down the street folks will say, ‘There goes the greatest hitter that ever lived.’” Born in San Diego on August 30, 1918, by the time Ted reached high school, he was an exceptional player who attracted the attention. It was his bat that first caught scout's eyes, but Ted excelled as a pitcher for the Hoover High Cardinals. He often struck out a dozen or more batters in a game, but he hit well, too, and found a place in the lineup for every game. Even while still a high school player, Ted signed his first professional contract with the locally-based San Diego Padres, of the Pacific Coast League. With the Padres, He got his feet wet in 1936, hitting a modest .271. He completed high school and then played for the Padres again in 1937, upping his average to .291 and showing some power with 23 homers. Boston Red Sox general manager Eddie Collins had spotted Ted while looking over a couple of Padres players and shook hands with owner on an option to sign the young player, which he exercised in time for Ted to go to the big league training camp in Florida in the spring of 1938. Ted was a brash and cocky young kid who was deemed to need a full year in the minors and he was assigned to the Minneapolis Millers, where he proceeded to win the American Association Triple Crown with a .366 average, 43 home runs, and 142 RBIs. There was no question that he would be with the Red Sox in 1939, and the buildup in Boston’s newspapers was unprecedented. The "Kid" was all that had been promised, and then some. Playing right field, he hit 31 home runs and batted .327. Not only did he lead the league in extra-base hits and total bases, he also led the league in runs batted in in his rookie year with 145, setting a major league rookie record that has never been beaten. His fresh and evident love of the game won the hearts of many Boston fans. The following year, 1940, he switched permanently to left field and improved his average to .344, though he dipped a bit in home runs (23) and RBIs (113). He placed first in both on-base percentage and runs scored. It was the first of 12 seasons that he led the league in on-base percentage; remarkably, he led in OBP every year through 1958 in which he was eligible. From his very first trip across country to spring training in 1938, Ted became known for his relentless questioning of other players about situational baseball. He seemed to live and breathe baseball and it rang true when he later acquired the nickname “Teddy Ballgame.” After a brief honeymoon with the press in the highly competitive newspaper town that was Boston, the critical stories began to come out. Taking on Ted sold newspapers, and writers could get under Ted’s skin, sometimes provoking a story where none had existed before. He was easy to mock, taking imaginary swings out in the field and letting a fly ball drop in. He was so cocksure that he turned off some of the crusty ink-stained wretches, and a little sanctimonious -- declining an interview with one of the deans of the press corps. Some of the writers had it in for Ted, and let him have it. There commenced a feud with the writers that lasted Ted’s whole career, and beyond. He enjoyed barring the scribes from the Boston clubhouse, sniffing the air distastefully as one walked by, and more than once spit toward the press box in contempt. There were fans who enjoyed egging Ted on, too, and during this second season he turned against the fickle fans. He later admitted he had “rabbit’s ears” and could hear the one loud detractor over the hundreds of cheering fans, and he let it get to him. He admitted he was never very coy, never very diplomatic. He blew up and would get so damned mad, throw bats, kick the columns in the dugout so that sparks flew, tear out the plumbing, and knock out the lights. One thing he determined never to do was tip his cap to the fans; even though there were days that he truly wanted to, he just couldn’t bring himself to do so. He was a complicated man and yet, despite all the tumult and turmoil, he never showed up an umpire by arguing a call and never got tossed from a game. And, though he preferred to keep to himself, he got along fine with other ballplayers, both on his own team and on opposing teams. It was in 1941 that The "Kid" had a season for the ages, batting .406 despite the sacrifice fly counting against the hitter’s average. Few players had achieved the .400 mark, and no one has done so since. He led the American League in runs and home runs. Two months after the season ended, Japanese warplanes attacked Pearl Harbor. Ted was exempt but that didn’t prevent some from questioning his courage when he chose to play baseball in 1942. He had already achieved national stature as a star baseball player at a time when baseball was unrivaled by any other sport. This made him a convenient target for criticism, but servicemen attending ball games cheered for him. Once he’d made his point, he signed up in the Navy’s V-5 program to begin training as a naval aviator when the season was over. In his fourth year of major league ball, Ted hit for the Triple Crown in the major leagues, leading both leagues, as it happened, with a .356 average, 36 home runs and 137 RBIs. And then it was off to serve. For the second year in a row, he came in second in MVP voting. He spent three prime years training and becoming a Navy and then Marine Corps pilot. He became so good at flight and gunnery that he was made an instructor and served the war training other pilots. He kept active to some extent, playing a little baseball on base teams but only as time permitted given his primary duties. Lt. T.S. Williams ended his stretch at Pearl Harbor and never saw combat. After the war, in 1946, Ted returned to the Red Sox and received his first MVP award from the baseball writers, helping lead Boston into its first World Series since 1918. He led the league in OBP, total bases, and runs, but an injury to his elbow while playing in an exhibition game to keep loose for the upcoming Series hampered his ability to compete effectively in the fall classic. The Red Sox lost to the Cardinals in seven games, and Ted’s weak hitting helped cost them the championship. In 1947, Ted had his second Triple Crown year, leading the A.L. with a .343 BA, 32 HRs, and 114 RBIs. The Red Sox didn’t come close to the Yankees that year, and in each of the next two years, they lost the pennant on the final day of the season. In 1949, he earned his second Most Valuable Player award and only missed an unprecedented third Triple Crown by the narrowest of margins. He led in homers and RBIs, but George Kell edged him by one ten-thousandth of a point in batting average. The year 1950 might have been his best ever. He had already hit 25 homers and driven in 83 runs when he shattered his elbow crashing into the wall during the All-Star Game. He missed most of the rest of the season, and said he never fully recovered as a hitter. In 1951, he led the league once more in OBP and slugging. Come 1952, as the war in Korea mounted, the Marines recalled a number of pilots to active duty. Among them was the less-than-pleased T.S. Williams, now a captain in the Reserve. When it was clear there was no choice but to comply, Ted determined to do his best. He requested training on jets and was ultimately assigned to Marine Corps squadron VMF-311 which flew dive bombing missions out of base K-3 in South Korea. Capt. Williams flew some 39 combat missions, though he barely escaped with his life on the third one when his Panther jet was hit and had to crash-land. The plane burned to an irretrievable crisp but Ted was up on another mission at 8:08 the next morning. It truly was an elite squadron to which he was assigned; on more than half a dozen missions, he served as wingman to squadron mate John Glenn. A series of ear infections consigned him to sick bay for two stretches and when it was obvious the war would be over in a matter of weeks, he was sent back Stateside and mustered out in time to be an honored guest at the 1953 All-Star Game. He threw himself into preparation to play and he got in 91 at-bats before the season was over, batting .407 in the process. Ted broke his collarbone in spring training in 1954 and missed so many games at the start of the season that come season’s end, he fell 14 at-bats short of having the requisite 400 to qualify for the batting crown he would have otherwise won with his .345 average. After the 1954 season, he “retired” and did not make a start in the 1955 season until May. He completed the year with 320 at-bats, but hadn’t lost his touch as indicated by his .356 average and 83 RBIs in the two-thirds of a season he played. In 1956, he had what by his standards seemed like a pedestrian, even somewhat lackluster year, accumulating an even 400 at-bats with 24 homers, but still hit at a .345 clip. A.L. pitchers were no fools; he drew over 100 walks and led the league in on-base percentage. The year 1957 is what was arguably the year in which Ted proved what a great hitter he truly was. He might have been “splendid” but he was no splinter. He’d filled out his physique, gone through war and divorce, suffered broken bones and pneumonia. Despite all the accumulated adversity, Ted hit .388 (just six more hits would have given him .400 again, hits that a younger man might have legged out) and led the league by 23 points over Mickey Mantle. His .526 OBP was the second highest of his career and so was his .731 slugging average. So, too, were the 38 home runs he hit. It was truly a golden year. His final three seasons saw a decline, though batting .328 as he did in 1958 would for almost any other player be spectacular. In fact, it was enough to win Ted the batting championship even if it was some 16 points below his ultimate .344 lifetime average. The batting title was his seventh, not counting 1954 as per the rules of the day. 1959 was his one really bad year as he developed a very troublesome stiff neck during spring training that saw him wear a neck brace and have a very difficult time trying to overcome it. He never truly got on track and batted a disappointing .254 with only 10 homers and 43 RBIs in 272 at-bats. It was sentiment alone that placed him on the All-Star squad, one of 18 times he was accorded the honor. Everyone expected him to retire, even Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey, with whom he had a good if distant relationship, suggested it might be time. Ted didn’t want to leave with a season like 1959 wrapping up his career. He came back for a swan song season, but insisted that he be given a 30 percent pay cut because of his underperformance in 1959. He felt he hadn’t earned the money he was being paid, at the time. I was just about the highest salary in all of baseball, understood to be around $125,000. He had hard work in 1960 but he produced, batting .316 with 29 home runs -- the last of which was hit in what had been announced as his very last at-bat in the major leagues. In his latter years, Ted had played for a Red Sox team that offered him little support in the lineup, had not much in the way of pitching, and didn’t draw many fans. Even Ted’s final home game drew just over 10,000 fans to Fenway Park. Leaving on such a high note, he couldn’t resist a final shot at the Boston press corps with whom he had so frequently feuded since his second year with the Red Sox. The “knights of the keyboard” wouldn’t have him to kick around anymore. And he left town, though in lieu of any farewell dinners he quietly, and without publicity, stopped to pay a visit to a dying child stricken with leukemia. Teddy Ballgame, as he was known, had been the leading spokesman for Boston’s “Jimmy Fund” for many years. Ted had appeared on behalf of Dr. Sidney Farber’s children’s cancer research efforts since the late 1940s, in fact since before Dr. Farber (the “father of chemotherapy”) first achieved remission in leukemia. Today, over 85 percent of children with leukemia are cured. After leaving full-time employment in baseball for good, Ted served for years and years as a “special assignment instructor” with the Red Sox. Typically, this meant he would show up at spring training for a few weeks and look over the younger hitters, occasionally taking a player aside later in the year as well. After the requisite five years following his playing career, he was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. When he was inducted in the summer of 1966, he wrote out his speech by hand the evening before (the original is in the Hall of Fame) and after thanking those who helped him on his way, he devoted part of the core of his speech to an impassioned plea that the Hall of Fame recognize the many Negro League ballplayers who had not been allowed to play in the segregated major leagues prior to 1947. For the last several years of his life, Ted became active in the memorabilia market, attracting very large sums to appear for occasional signings at industry shows. His son, John-Henry Williams, took over management of the marketing of his father with mixed success. Many criticized John-Henry for being too zealous in his father’s behalf and for some of his business schemes, but there was no doubt that Ted very much loved his son and was prepared to turn a blind eye to any faults. Ted suffered a stroke and a subsequent heart operation sapped his health, and he entered a period of decline that ended with his passing on July 5, 2002 at age 83. In death, as in life, controversy swirled around him as two of his three children had his body cryonically frozen for the possibility of some later revival if science someday learns a way to restore life to those who have been so preserved. Finally, an outpouring of more than 20,000 people attended a memorial at Boston’s Fenway Park in July 2002. |

|

|