|

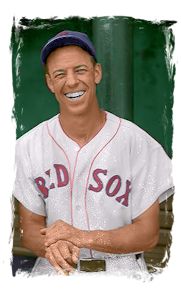

Bill Werber was born on June 20, 1908 in Berwyn, Maryland. After starring in baseball and basketball at Tech High School in Washington, D.C., he was awarded a partial athletic scholarship to Duke University, where he became Duke’s first basketball All-American. He also starred on the baseball team, quickly catching the attention of the New York Yankees. In the spring of 1927, after Bill's freshman year, the Yankees signed him to a handshake deal, with a five-figure bonus and a promise to finance the rest of his college education. After he graduated from Duke in June 1930, he reported directly to the Yankees, just as promised in his handshake agreement. He played in four games for the Yankees, before the Yankees sent him to the Albany Senators in the Eastern League so that he could play every day. After the season, he enrolled in the Georgetown University School of Law in Washington with designs on joining an uncle’s law firm. The Yankees, however, made it clear that if he wanted to pursue a baseball career, he would need to report to spring training in March, and so after one semester, Bill dropped out of law school. In 1931 he reported to the Toledo Mud Hens. In midseason, with the Mud Hens having trouble making their payroll, the Yankees transferred him to the Newark Bears of the International League. For 1932 the Yankees assigned the still 23-year-old to the Buffalo Bisons, also of the International League. Her had a .289 average for a third-place team. But his performance resulted in an invitation to the 1933 Yankees’ spring training in St. Petersburg, Florida. He had a strong spring at the plate, however, batting .345 and running the bases aggressively, but his erratic throws to first base gave the Yankees pause about whether he could be the everyday shortstop. The Yankees ultimately decided to go with Frankie Crosetti, who would hold down the position for more than a decade and play in seven World Series. Although Bill played a few regular-season games with the Yankees, in May the team sold him to the woebegone Boston Red Sox, who had finished dead last in 1932. Bill, however, played regularly for an improved Red Sox club and began the transition to his more natural position at third base. For his first full year, he hit batted .258 and swiped 15 bases to tie for fifth in the league. His 39 errors, many on throws, were still a cause for concern. In 1934 he was on his way to the MVP award, and the team still jumped from seventh in 1933 to fourth place. He again led the league in stolen bases. In July he tied an American League record with four doubles in one game. He improved to .275 in 145 games in 1936 as the Red Sox slipped to sixth place. After the season the club traded him to the Philadelphia Athletics for Mike Higgins in a straight swap of third basemen. In 1937, Bill hit .292 and tied for the league lead in stolen bases. He declined to a .259 average in 1938 as the A’s won the race to the bottom of the American League by two games over the St. Louis Browns, finishing dead last. Bill found himself sold to the Cincinnati Reds on March, 1939. The Reds swept to the pennant by 4½ games over the St. Louis Cardinals and Bill batted .289 leading off and led the league in runs scored with 115. His cocky and aggressive nature got him into several fights or near fights during his career. He had a memorable run-in with legendary New York sportswriter Red Smith during the 1939 Series. Smith, who was admittedly put off by Bill’s cocky and sometimes arrogant manner, had over the years written some columns critical of him. In 1935 Babe Dahlgren was a rookie first baseman with the Red Sox and Bill took loud exception at the end of an inning to a sloppy play by Dahlgren on a ball hit to him at first. The two exchanged punches before teammates separated them. In 1940, Bill had another strong year in the leadoff slot, hitting .277, finishing third in the league in runs scored with 105, and fourth in steals with 16. In the 1940 World Series the Reds met the Detroit Tigers, who had broken the Yankees’ string of four straight pennants. Going into 1940, Bill had fully expected to retire from baseball after the season. His sore toe from his unfortunate bucket kick in 1933 still plagued him and caused pain in the back of both legs. But the success of 1940, coupled with the prospect of a nice raise, compelled him to change his mind and sign on for 1941. The 1941 Reds were still a good club, but they were aging and plagued with injuries. They finished in third place, 12 games behind the pennant-winning Dodgers. Bill slipped to a .239 average, and his errors increased to 30 in 109 games. In 1942, the Reds sold him to the New York Giants. He reported to the Giants’ spring training camp in Coral Gables, Florida, in March. Bill created a good deal of controversy when he published an article in the Saturday Evening Post titled “Ballplayer Boos Back.” In his typical outspoken manner, the article details the difficulty and pressure of playing baseball at the major-league level and is critical of the lack of understanding of sportswriters and fans. Of course, the’s provocative title was designed to garner attention, and it did. It also helped cement his reputation as a malcontent. He struggled in 1942, with his average hovering around the .200 mark. His toe became increasingly painful and at one point he entered New York’s Presbyterian Hospital to have the sciatic nerve in his right leg stretched. Finally, with about two weeks left in the season, he retired and left the team. Although Bill was through with baseball, it was not yet through with him. He returned to Washington to work in the insurance business, but shortly was contacted by Clark Griffith, the owner of the Washington Senators. World War II was in full force and major- league baseball was losing ballplayers to the military in droves. Griffith has lost his third baseman, Buddy Lewis, to the Army Air Corps, and offered Bill the then princely sum of $13,500 to play for the Senators in 1943. He turned the offer down, telling Griffith that it would cost him more than $10,000 to leave his insurance business. He later reported that he had been correct: He earned $100,000 in commissions on almost $2 million worth of life insurance policies in 1943. After his retirement from baseball, he continued to run, very successfully, the family insurance business until he retired in 1972. In retirement Bill became a scratch golfer and competed well in amateur tournaments along the East Coast. He continued to be an avid bird hunter and wrote a self-published book, "Hunting is for the Birds", about his bird-hunting experiences. He referred to baseball as not a career, but a job that enabled to him to support his family in a comfortable manner, and nothing more. In 1978 ,he wrote a self-published memoir of his life titled "Circling the Bases", which emphasized his baseball career. Bill Werber lived a long and satisfying life and was, for a time, the oldest living former major-league player. For many years, her suffered from diabetes and gave himself insulin shots several times a day. When he was in his 90s he lost a leg to the disease. The occasion of his 100th birthday on June 20, 2008, brought him national press attention and a large party in his honor in Charlotte, North Carolina, where he spent his last years. He died on January 22, 2009, at age 100. |

|||||