|

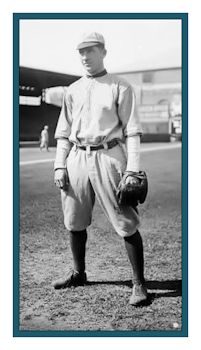

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||||

Del Pratt was arguably the second-best second baseman of the second decade of the 20th century. He was born into a well-off family on January 10, 1888, in Walhalla, South Carolina, near the Georgia-North Carolina border. Del was wild about baseball at a very early age. He started at Alabama Polytech (now Auburn University) and soon transferred to the University of Alabama, where he studied textile engineering. He earned varsity letters in both baseball and football in 1908 and 1909 for the “Thin Red Line” (the team’s nickname before the “Crimson Tide.” Del played shortstop and was team captain both years, including the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association champions of 1909, with a 19-3 record. He was elected to the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame in 1972, along with Satchel Paige and (posthumously) Heinie Manush. After graduating from Alabama in 1909, where Pratt studied law (but did not get a law degree), he entered professional baseball in 1910 with a Class A club, Montgomery (Alabama) of the Southern Association. He hit only .232 and was sent to Hattiesburg (Mississippi) of the Class D Cotton States League that same year. His .367 average in 20 games brought him back to Montgomery in 1911. Not only did Del continue his solid hitting (.316 in 139 games) but he also showed his speed with 36 stolen bases. He led the league in batting average, hits, and runs. He still found time to stay connected to football, coaching Southern University in Greensboro, in 1910. It was the first of more than a dozen years in a row that Pratt would coach college athletics in the off-season. The St. Louis Browns acquired Pratt for players and cash, along with a $250 signing bonus. He averaged 156 games a year, leading the league in games four of the five years. He hit between .283 and .302 four of the five years, with 26-35 doubles and 10-15 triples a year. He averaged 80 runs batted in and almost 70 runs a year, during the low-offense "Deadball Era", and averaged 80 runs batted in and almost 70 runs a year. Pratt had a sparkling rookie season with a .302 batting average with 26 doubles, 15 triples, and a .426 slugging average. He accomplished all this on very weak teams. Only in 1916 did the Browns have a winning record. That was the first full season of another Brownie and former college star, the University of Michigan’s George Sisler. In 1915, the two former college men were roommates on the road. Pratt also showed surprising power in his rookie season with five home runs. A year later, he ended Walter Johnson’s scoreless inning streak at 55-2/3, by driving in a run with a single. The numbers reflected the maturation of his glove skills. Del had tremendous range, leading the American League in chances and putouts five times, and double plays and assists three times. In the `teens, from 1913 to 1919, his chances per game were more than those of Eddie Collins, often by a large margin. In 1915, when Browns’ manager Branch Rickey made a recruiting trip, he put his young second baseman in charge of the team. In 1916, when Del’s batting average dropped to .267, he led the league in runs batted in with 103. 1917 was a difficult year for Pratt, as he was seriously hampered by injuries for the first time in his major league career. The Browns were a team ridden by factionalism at the time. They were a combination of the Federal League’s St. Louis Terriers as well as the Browns. In late October 1917, the New York Yankees fired manager Wild Bill Donovan after a disappointing sixth-place finish. The Yankees hired the bright skipper of the Cardinals, Miller Huggins. The deal was done, and the new manager, a second baseman himself in his playing days, was familiar with Pratt, and so New York went after him. They Yanks got a lot of production from Pratt. Besides his solid glove-work, Del averaged .295 the next three seasons, with both extra-base hitting and speed on the base paths. He continued to show his durability. Je played in all but one game in 1918-1919-1920. Then there was the Del Pratt off the diamond. The University of Alabama had offered Del a contract to coach their football team. In his defense, it was reported that the Yankees had offered him the same $5,000 salary he had in St. Louis in 1917. The Alabama offer enabled Del to keep his options open. The Yankees improved to fourth place in Huggins’ first season at the helm. The 1919 Yankees were in the pennant race well into the summer. Their pitching had been bolstered by the midseason acquisition of pitcher Carl Mays from the Red Sox in exchange for pitchers Allan Russell and Bob McGraw and $40,000. There were some newspaper reports that Boston would get another player as part of the deal. On August 1st, it was reported that Pratt would be that man. There never was another player sent to the Red Sox in that deal, nor was there any further explanation. In late March of 1920, a controversy erupted in the Yankee clubhouse over the distribution of third place money among the team members. Del led the protesters’ charge and even suggested that the players would strike over the matter. Press reports quickly surfaced that the Yankees were unhappy with him and might trade him. 1920 was the Yankees high point in wins, with 95, but the Cleveland Indians were the team that won their first pennant, with 98 victories. The Yankees were in the race until the end of the season, occupying first place as late as mid-September. Pratt usually batted cleanup or fifth, right behind the newest Yankee, Babe Ruth. It was also Pratt’s finest season so far in his nine-year career: highs in batting, on-base, and slugging averages (.314, .372, .427), and highs in hits and doubles (180 and 37). On August 23, 1920 Del had perhaps his finest game at the plate. He knocked in seven runs with five hits, including a double and a home run. The 1920 season was also the high-water mark of anti-Huggins sentiment in the press and plotting in the clubhouse. While the Yankees improved their record in each of his first three years in New York, there were constant rumors swirling that Huggins would be replaced. He had few supporters, as much because of his introspective personality as because of his small size, which translated into stature in that era. Moreover, expectations were very high in 1920, after the team had acquired Babe Ruth that January. Some of the Yankees were pushing Roger Peckinpaugh, who had run the team late in the 1914 season, as his replacement. Pratt was one of the anti-Huggins agitators (though Peckinpaugh was not), and he certainly did not discourage suggestions that Del would make a good successor to the little skipper. His relations with Miller Huggins strained to the breaking point, Del began to consider career alternatives that summer, even though he was only 32 years old. The coaching staff University of Michigan was in transition at the time. Pratt wrote the AD that after he met with the “two owners” of the Yankees, he came to the conclusion that it was every man for himself. On August 7, 1920, he signed a three-year contract to become the coach of the Michigan baseball team and the assistant coach of the school’s football and basketball teams $4,750 a year. He had been making $6,500 with the Yankees. The Yankees then traded Pratt as part of a blockbuster deal with the Red Sox. Del, young catcher Muddy Ruel, and two others went to Boston for a temperamental yet talented young pitcher named Waite Hoyt, veteran catcher Wally Schang, and two others. The Boston press was quite positive in evaluating the 1920 Pratt trade. This comment from the Boston Globe was typical: “Schang and Pratt are the two big players in the deal, with Hoyt something of a speculation, and unless the latter should develop into a great pitcher, it looks as if the Yankees were stung.” There were also reports that Boston’s fine shortstop, Everett Scott, had been clamoring for the team to get Pratt for some time. Burt Whitman of the Boston Herald gushed that the deal must have been “conscience money” from the Yankees for the Babe Ruth deal “for surely the Sox get the cream of the talent.” And so Del Pratt was sent from the Yankees, just as they were about to embark on a decade of dominance, to the Red Sox, a team entering a decade of despair. For a while, it seemed that Del would not report to the Red Sox and would retire from baseball. The day after he was traded to the Red Sox, the Michigan athletic director, P.J. Bartelme, was emphatic that Del was under contract to his school. Red Sox owner Harry Frazee said that he’d offer Pratt far more money to stay in baseball. In late February 1921, Pratt wrote Frazee that “it is impossible for me to resign but if you as an outsider can make it possible for me to leave with a clean slate,” he’d like to play for the Red Sox. Frazee wrote Bartelme that his situation needing Pratt was desperate. Only the cellar-dwelling Philadelphia Athletics had a lower batting average in the American League. Pratt told Bartelme he would never think of quitting and would honor the contract, but that the Boston offer was a good opportunity for his family. Del said the two-year offer would amount to $25,000 including bonuses. A clipping in his file at the University of Alabama archives noted that Boston had sent Del a blank contract and let him fill in the salary amount. He inserted $11,500 a year for two years, which would have been one of baseball’s higher salaries at the time. Del offered to refund half the salary he had received up to March 1st to the university. He also offered to return each off-season for the next three years to assist in coaching the school’s football and basketball teams. On April 21, 1921, the Board of Control of Athletics at the university considered the Pratt case and accepted his proposal. Del maintained a close relationship with the University of Michigan. He helped football coach Yost during the baseball season for a few years and also coached the freshman basketball team. He was such a favorite of the school that when the Red Sox first visited Detroit during the 1921 season in mid-May, the Tigers had a "Del Pratt Day", with a section of seats set aside for Wolverines fans. Del was even honored one evening that week at a university banquet. He had a terrific season in 1921, with career high marks in batting, on-base, and slugging averages (.324, .378, .461). His eye was better than ever andhe struck out only ten times in 521 at bats. While he was slowing down on the basepaths, with only eight steals, his glove-work still sparkled. He teamed with shortstop Scott for 90 double plays. Del had another strong year in 1922, with career highs in hits, doubles, and total bases (183, 44, 259). Only now the Red Sox were a last-place team, after finishing in fifth place the year before. Gone were pitchers Sam Jones and Joe Bush, who had won more than half of the team’s games in 1922. Gone also was Everett Scott, and in midseason, third baseman Joe Dugan. All four had been traded to the Yankees. On October 30, 1922, Del was traded to the Detroit Tigers in another multi-player deal. The key man the Red Sox got was pitcher Howard Ehmke. Ty Cobb had long admired his hitting skills and durability. After leading the league in late July and being only a half-game back in mid-August, they finished six games out of first place. While Del’s bat was as potent as ever, hitting over .300 both seasons, it was not a good trade for the Tigers. Del turned 35 shortly after the trade and missed 86 games in 1923-1924. The worst part of the deal from the Tigers’ standpoint was that they gave up on an excellent pitcher. Howard Ehmke won 39 games in 1923-24, an incredible 30 percent of the Red Sox victories. In 1924, as in 1915 and 1916, the Tigers might have been just one starting pitcher away from the AL pennant. Despite hitting above .300 for five straight seasons (in which he averaged almost 500 at bats), Del was released by the Tigers after the 1924 season and waived out of the league. He had slowed down significantly in the field, as reflected in his lower Chances per Game numbers. He finished his major league career with just under 2,000 hits, of which 20 percent were doubles and 25 percent were doubles and triples. Del was one of the few men who played regularly (more than 120 games) and hit over .300 in both his first and last major league seasons. He was also one of a handful of players who appeared in all of his team’s games over three seasons for three different teams (Browns, 1913, 1915, 1916; Yankees, 1918, 1920; Red Sox, 1922). Another player who started in St. Louis, Rogers Hornsby, matched that mark, with the Cardinals, Giants, and Cubs. So Del embarked on a career as player-manager for the Waco Cubs of the Texas League. At the age of 39, Del put together one of the great seasons a player-manager in the high minors ever had. He won the Texas League Triple Crown: a .386 batting average with 32 home runs and 140 runs batted in. In 1931, when Texas League ball moved back to Galveston (from Waco), Del went along as manager of the Galveston Buccaneers for two seasons. In 1931, he watched a couple of future St. Louis stars excel with Houston: Dizzy Dean and Joe Medwick. And the following year, former Browns teammates Hank Severeid and George Sisler (the latter for just part of the season) were fellow Texas League managers. In 1932, Del had his last plate appearances at the age of 44, when he hit .293 in 41 at bats. In 1933 Del was out of baseball, while he operated a bowling alley in Galveston. He returned as manager and business manager of the Fort Worth Cats the following year for his final season managing baseball. Three years later, he was one of 403 retired players who received lifetime passes from major league baseball. He continued to live in Galveston for the rest of his life. For many years he owned a gas station at 31st and Boulevard. In a rich baseball career of more than two decades, including thirteen years in the bigs, Del Pratt was part of a lot of baseball history. He lived for more than 40 years after leaving the Detroit Tigers. When he was inducted into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame in 1972 at the age of 84. Del died on September 30, 1977 at age 89.

|

|||||