|

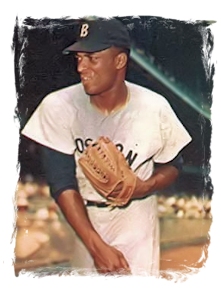

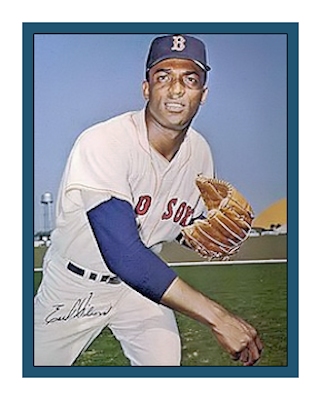

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||

Ponchatoula, Louisiana, in the 1930s was a small town that had suffered a number

of lumber mills closing in the previous decade. It was into this area that on October

2, 1934, Earl Wilson was born. He grew up loving sports and went to Hammond Colored High School, where he

played varsity basketball. His passion, however, was baseball and he played

whenever and wherever he could get the chance. He played at Athletic Park in

Ponchatoula for as many community teams as he could.

He began playing as an outfielder but soon switched to catching. He was

always a strong hitter. In 1953, because of his strong arm, he was

changed into a pitcher. He went he went 4–5 with a 3.81 ERA for the Bisbee-Douglas Copper Kings of the Arizona-Texas

League.

It was during this 1953 season that the Boston Red Sox began to notice the young ballplayer. That year the Red Sox signed him and he was the first African American to sign with the Bosox because Pumpsie Green, wasn’t signed until 1956.

Earl was then drafted into the Marines in 1957. In July, 1959,

Pumpsie made his debut becoming the first African American to play for

the Red Sox and one week later, Earl made his first Red Sox appearance.

During the remainder of that season, Earl appeared in nine games and compiled

a modest 1–1 record with a 6.08 ERA. Besides his pitching, he also showed his bat was a serious weapon.

In the 1960 season, he appeared in 13 games and lowered

his ERA to 4.71, also lowering his walk to strikeout ratio as well. His control at

this early stage of his career was always a concern. In spite of what appeared

like good progress hewould not make a major league start in 1961.

The following season, 1962, saw him come back to stay. It did not take long

for him to distinguish himself. On June 26 of that year, he took the mound

against the Los Angeles Angels and Bo

Belinsky in front of 14,002 fans in Fenway Park and hurled a no-hitter, pitching the Sox to a 2–0

win. He also helped his own cause by hitting a home run, which proved to be the

game-winning run. He faced 31 Angels hitters, gave up four base on balls, struck

out five, had eight ground-ball outs and 14 fly-ball outs. Tom Yawkey gave Wilson a $1,000 bonus for his achievement, The victory was his sixth of the season and he went on to finish the year with a 12–8 won-lost record with a 3.90 ERA. And for the first time his strikeouts outnumbered his walks (137–111).

It was also in 1962 that he became one of the first professional athletes to have an agent represent

him in contract negotiations. It occurred as a result of a minor accident in

which he was involved. He was referred to a young lawyer by the name of Bob Woolf

and his association with Earl marked the start of Woolf’s career

as a sports agent. It worked out well for both parties, as besides being involved

in contract discussions for Earl, Woolf also achieved several endorsement deals

for the player.

Earls next few seasons saw his won-lost record reflect the overall ineptitude of

the Red Sox. In 1963, he earned 11 victories and 16 defeats. Still, he lowered

his ERA to 3.76.

The 1964 season saw him compile an 11–12 record with a 4.49 ERA. In the 1965 season Earl had 13 wins to

lead the Red Sox. He also had 14 losses with an ERA of 3.98.

Early 1966 saw an event occur that had a monumental effect on the rest of

Earl's life. During spring training, while in Lakeland, Florida, he and a couple of his

teammates, Dennis

Bennett and Dave

Morehead,

decided to go to a local bar named the Cloud 9 for a drink after a day at the

park. The bartender

asked Morehead and Bennett what we wanted and then turned to Earl and said, `We don’t

serve niggers in here.’ They all got up and left the place and Earl was upset

because he had never been refused service before.

In June, the Red Sox acquired two black players, John Wyatt

Jose Tartabull. The next morning manager Billy

Herman informed

Earl that that he and a black outfielder, Joe Christopher, had been

traded to Detroit. Earl at the time had appeared in 15 games with the Sox that season

and had a 5–5 record. His ERA was 3.84. Although upset at first, Earl finished

the year with 18 wins overall and a sparkling Tigers ERA of 2.59.

For Earl, 1967 was without doubt his finest season. He had 22 wins against just 11 defeats

and also racked up

184 strikeouts. Detroit finished the season just one game behind the “Impossible

Dream” Red Sox.

In 1969, Earl had his last winning season as a pitcher and finished with a

12–10 record and a 3.31 ERA. The 1970 season was his final one in

the majors. He was sold to the San Diego Padres in July, and they finished

the year. Earl was subsequently released by the Padres in January 1971, at which

time he promptly retired from baseball.

In 11 seasons in the big leagues, Earl had a 121–109 record with a lifetime ERA

of 3.69. He had 35 home

runs in 740 at bats.

Upon his retirement, he decided to move back to Detroit for several reasons.

Detroit was one of the few areas that he had been where blacks actually owned

businesses rather than being employees. His greatest success as a major leaguer

happened there and the area had a large number of successful middle-class

blacks, many of whom were also entrepreneurs.

The world lost Earl Wilson on April 23, 2005, to a heart attack at his home in Southfield, Michigan, at age 70.

|

|||