|

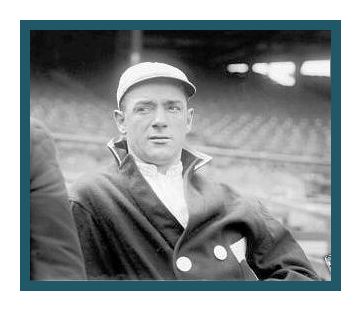

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||||||

Although never regarded as especially fast, the longtime Red Sox shortstop and coach made a name for himself for covering wide territory from deep short and occasionally slipping his oversized feet in front of opposing base runners to trip them up as they headed for third. On and off the field, his quiet leadership, dogged loyalty and wry humor earned him the respect of teammates, adversaries, and fans in Boston for over two decades. His nickname, “Heinie,” was a lifelong reminder of his German ancestry, but Charles Francis Wagner, son of German-born John Wagner and American-born Catherine Siedle, born in New York City on September 23, 1880, was as American as they came. As a boy, Wagner mastered the inside game in gritty fashion, playing barefoot on the rough-and-tumble side streets and vacant sandlots of Harlem. His first experience on the baseball diamond took place on the streets of Manhattan, and by the age of 17 he was among the most prominent amateurs on the island. Believing there was no better way to “gather in easier money than in baseball,” after graduating from high school in 1898 Wagner landed his first regular paying work on the New York semipro circuit, earning a dollar a game for the Murray Hills nine. In the spring of 1902, after a brief jump to Waverly in the New York State League, Wagner signed on to play short with the Columbus Senators, the smallest by population of the six charter cities in the newly re-formed American Association. Wagner’s break into the big leagues came in Columbus at midseason of 1902. Desperate to fill the spikes of ailing Joe Bean at shortstop, in late June John McGraw offered Wagner a shot with the Giants in New York. Wagner made 17 appearances over the next two weeks, hitting .214 in 56 at-bats, but McGraw – perhaps mistaking Wagner’s mellow demeanor as a lack of competitive fire – was unimpressed. He handed Heinie his unconditional release on July 17. The following spring, Heinie signed on with Walt Burnham’s Newark Sailors in the Eastern League (today’s International League). He never hit better than .241 in his four years with the club, but his deft fielding and deadly accurate arm solidified his reputation as a premier middle infielder. His contract was picked up by the New York Americans. Almost overnight, and amid little fanfare, the Highlanders turned him over to owner John I. Taylor and the Boston Americans. On September 26 in Chicago, Heinie Wagner appeared in the first of the 805 games he would eventually play in a Boston uniform. He committed an error to open the contest but went on to nail out two clean hits to win accolades from the press. “Wagner played a great game,” the Boston Globe wrote the next day. “He has all the earmarks of a real find.” A “real find” was exactly what the beleaguered 1906 Boston team needed that summer. Only two years away from championship glory, Taylor’s club had inexplicably sputtered and spiraled their way from first to dead last in the American League. Taylor, hoping to infuse his aging club with young guns, made Wagner and rugged Holy Cross catcher Bill Carrigan the first installments of a team Taylor vowed would be rebuilt on youth, power, and, above all else, speed. Wagner’s work in late 1906 was more than enough to earn him an invitation to train with Boston the following spring, and on March 1 he dutifully joined his teammates aboard the 9:50 A.M. train out of New York bound for Little Rock. It was a taxing summer from the outset. After enduring five weeks of camp as a rookie newcomer, on the eve of opening day Wagner and his teammates were rocked by the horrifying suicide of enormously popular manager, Chick Stahl. For Wagner, the season only went downhill from there. Playing under no fewer than four managers over the next five months, Wagner fought bitter battles with disgruntled Freddy Parent, who was none too pleased to be dumped from his regular position at short to make way for the upstart Wagner. In October, John I. Taylor put an end to the conflict by sending Parent to Chicago. Wagner etched steady work for himself with the newly christened Red Sox, club president Taylor followed up on his earlier promise and, one by one, assembled one of the youngest, swiftest squads in baseball: Eddie Cicotte, Harry Lord, and Tris Speaker; Joe Wood, Larry Gardner, and Ray Collins; Harry Hooper and Duffy Lewis. Off the field, they were cliquish and at times their own best enemies, divided – like most of America at the time – along the seemingly impenetrable lines of religion and ethnicity. But on the field it was a different matter. Clubhouse tensions centered on ongoing ill-will between Catholics Lewis, Wagner, and Carrigan and High Mason Tris Speaker, and flared into open warfare more than once. In early August of 1910 things came to a head once again, this time over disgruntled team captain Harry Lord. On April 20, 1912, Heinie Wagner went 1-for-5 and stole a base in Boston’s 7-6, 11-inning victory over New York to officially open Boston’s new ball field, Fenway Park. The player-manager of any baseball team of the time also functioned as the captain of the team, but this was not the way the Red Sox were organized in 1912. Jake Stahl managed the team and also played first base, but Heinie Wagner was the Red Sox captain. What manager Stahl said before the game was law, but once the game started, and Jake covered the first base bag, Heinie Wagner took over control on the field, and the manager became just another player who took orders from Wagner over at shortstop. The system worked well, much to the astonishment of baseball purists of the time. Wagner would not come close to his work at the plate in 1913, as the season before, hitting a disappointing .227, but in the field he turned out the finest defensive effort of his career. One of his specialties was covering second base on steals. He could take the catcher’s throw on a run, often one-handed, and apply the tag just in the nick of time. Ty Cobb admitted that Wagner caught him far more often than did any other infielder in the American League. Injuries dogged the veteran players and ultimately doomed the team to fourth place. Wagner dealt with episodes of infection from spike injuries, blood poisoning, and shoulder and arm pain that relegated him to the sidelines on several occasions, allowing greater opportunities for Harold Janvrin to preside over the shortstop position. And when spring training rolled around in March 1914, it looked as though Heinie Wagner’s days in Boston might well be at an end. Over the winter, fans in Boston read that Wagner would likely be bumped to second base to make room for the enormously promising Everett Scott, who was already drawing a hefty salary from the franchise. When he arrived in Hot Springs with Carrigan in March, Heinie appeared sickly and thin. He did not bother donning his uniform, limiting his workout to solo walks through the Hot Springs hills, and reporters looked on in disgust as he relied on teammates to cut his meat at the hotel dining room. Days later, accompanying sports scribes revealed that he had suffered an attack of rheumatism over the winter and was being shipped back north for treatment. In late June Bill Carrigan called Wagner back to Boston to serve as his third base coach and “all around right eye.” Wagner and Carrigan collaborated on strategy as well. They were inseparable friends and celebrated their accomplishments together. Rumors about Wagner’s future in Boston continued to percolate over the winter of 1914-15. One was that he was negotiating a jump to the Federal League; another had it that he was to take over as manager of the Eastern League Providence Grays. However, when the first day of training rolled around at Hot Springs in March, a surprisingly healthy Heinie Wagner was in uniform and ready to play. Now largely a utility infielder, he hit a modest .240 in 84 games in 1915 as the Red Sox won the pennant and spent his nonplaying time coaching at third. Wagner also found himself saddled with an additional, unforeseen duty on the road: overseeing the off-the-field shenanigans of a raw rookie from Baltimore, Babe Ruth. Heinie was included on the eligible players list, but he did not make an appearance during the Series, and instead collaborated with Bill Carrigan on strategy. Under the duo of Carrigan and Wagner and armed with a new generation of young guns on the mound, the Red Sox put their differences aside and again clawed their way to World Series victory, this time whipping Grover Cleveland Alexander and the Philadelphia Phillies, four games to one. Fresh from victory, in January of 1916 the Red Sox released Wagner unconditionally, the franchise revealing only that he “might obtain a berth as a manager in one of the minor leagues.” Carrigan, on June 28 once again called him back to Boston. The Red Sox were on their way to a second straight AL pennant by September, when Carrigan surprised Hub rooters by confirming his intention to retire when the season was out. Even the sweetness of a second straight World Series pin and promises of more money could not sway the resolute Carrigan, who over the winter affirmed that he was through. Wagner’s name was mentioned prominently as a possible replacement for Carrigan, but in January Red Sox owner Harry Frazee announced captain and second baseman Jack Barry as the “logical choice” to manage the club in 1917. With Heinie again at third, Boston rolled up 90 wins to finish second in the AL, nine games back of pennant-winning Chicago. At the close of 1917, Harry Frazee assured Wagner that he would be back with Boston in 1918, and over the winter Wagner received a copy of his contract in the mail as usual. When Frazee hired Ed Barrow to replace Jack Barry at the helm of the team, however, the Red Sox owner did an about-face, announcing that he was dumping Wagner at third in favor of former Chicago Cub Johnny Evers. The Evers experiment was doomed almost from the start. On the return trip from Hot Springs, weeks of tension between the sharp-tongued Evers and the explosive Barrow collapsed into all- out war. On opening day, April 15, Barrow issued a terse statement that Evers had been released and Wagner called back to Boston. With Evers awkwardly looking on from the Fenway Park grandstand, that afternoon Heinie was again in uniform and standing at his old post at third. Once again, it seems, the Red Sox needed Heinie Wagner far more than he needed them. Still, as he had done for a dozen years now, Heinie Wagner served his team with loyalty and dedication. He did his level best to keep an eye on an increasingly cantankerous Babe Ruth, and it was Wagner who was ordered to Baltimore to retrieve the slugging pitcher when he bolted the club in early July. In February 1919, Wagner was out again as part of the Red Sox club. There was a player limit imposed on teams, and non-essential personnel were cut. Wagner got his release once again. In April, he and Bill Carrigan teamed up again and looked into purchasing the rights to the Portland club of the New England League. Wagner would return to the Red Sox in 1927, brought out retirement by his old pal Carrigan to resume work at third base, but manager Carrigan had been handed little material to work with, and neither he nor Wagner was able to rekindle the magic of the previous decade. When Carrigan had seen enough at the close of the 1929 campaign, Heinie took up duties as manager but with no more luck. After piloting the woeful 1930 Sox (52-102) to a last place finish in the American League (a whopping 50 games back of pennant-winning Philadelphia) to no one’s surprise Heinie resigned the day after the season ended.

|

|||||||