|

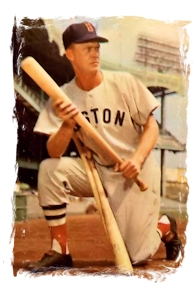

Walter "Hoot" Evers was born on February 8, 1921, in St. Louis. When Walter was a child, he loved to cheer for Hoot Gibson, the cowboy movie hero. On Saturday afternoons, he and his buddies would play Wild West games and he insisted on impersonating Hoot because he liked to win. Soon his buddies began calling him Hoot and the name stuck for the rest of his life. In high school, Hoot won local fame as Township High’s star athlete. He hurled the javelin farther than anyone else at track meets, was a triple-threat quarterback in football, excelled at basketball and became an all-state forward. He was also a very good tennis player. Even though his favorite sport was baseball, he couldn’t play, as Township had no baseball team. After graduating, he entered the University of Illinois and played baseball and basketball and threw the javelin for the track team. After the school year, he came to Detroit for a summer tryout and after he went back to school, he wanted to drop out and start his professional career. Barely out of his teens, he couldn’t wait to get his career started. The Tigers assigned him to their Texas League farm in Beaumont, where he spent just one week, batting .174, before moving to Winston-Salem in the Class B Piedmont League. He got a chance to play a game for the Tigers in September in Washington. The next year, 1942, Hoot rebounded to have an outstanding season for Beaumont, showing the Tigers brass just what kind of player he could be, improving his batting average to .322 After the season, with World War II raging, Hoot enlisted in the Army and was assigned to the Waco Army Air Field in Texas for training. He spent the next three years in the Army Air Force but never saw combat, instead playing baseball for the Waco Wolves service team. Hoot rapidly became a star for the club, which swept through tournament after tournament and his batting average over those three years was .467. He turned down a chance to attend officer candidate school, even though he had all the qualifications., because he simply wanted to play baseball for a living. With the war over, Hoot was discharged in time for the 1946 season. He showed the need for experience, of course, but he played like a guy who had been around the American League for several years. But soon the injury bug began to hit him and it would continue to do so for the rest of his career. He led the team in hitting, fielding, and baserunning in the first half of the Tigers’ exhibition schedule and had the center-field job all but sewn up. But in March, as he began a slide into second base, a relay throw hit him in the hand and fractured his thumb. In throwing up his hand, he failed to pull in his foot when he started his slide and his ankle snapped. With his thumb and ankle fractures, the doctors told him it would be two or three months before he could be back playing. When he came back, in a game in June in Washington, a low fly ball was hit to short center field. Hoot and second baseman Eddie Mayo collided. The two players were carried off the field on stretchers and taken to Georgetown University Hospital. Hoot suffered a compound fracture of the jaw, along with some internal injuries and doctors doubted whether he would ever play again. Surgeons wired his jaw and three weeks later, against the Yankees, he fooled everybody by returning to the lineup. The injuries had taken their toll, though. He had been one of the fastest outfielders in the game, but the fractured ankle had robbed him of some of his speed and the fractured right thumb had hurt his throwing ability. He hoped for better luck in 1947, but the injury jinx was still with him. In June, in a game at Detroit, he was hit in the left temple and was taken to a hospital, but he returned in 12 days and went on to hit .296. Healthy for the 1948 season, Hoot hit .314. and hit a homer in the 1948 All Star Game. In July he crashed into the left-field fence at Fenway Park for an impossible catch of a drive. He scraped an elbow and cut his left hand, but refused to be benched. It was another fine year for him, with a batting average of .303. Hoot had his greatest season in 1950. His 143 games were a career high, and he never came close to approaching that total again. He had a league-leading 11 triples, 21 home runs, and 103 RBIs. Coming off a great season, Hoot figured he would cash in with a nice raise, but in 1951 the injuries returned and he played in only 116 games. His batting average fell almost 100 points, to .224. He was determined to bounce back the following year and reported to spring training for the Tigers in 1952, feeling good and looking forward to getting back to his 1950 stats. But in an exhibition game against the Cincinnati Reds four days before the start of the season, he was hit by a pitch and his thumb was broken in two places. When he came back, after just one plate appearance with the Tigers, he was traded to the Boston Red Sox in June. With Ted Williams serving with the Marines in the Korean War, the Red Sox needed an outfielder and acquired Hoot as part of a nine-player deal. He hit .262 for the Red Sox and could still play a good outfield, and at 30, was young enough that Boston hoped he could regain his form. But in 1953, he played in just 99 games, and hitting .240. Hoot was no longer the same player as the injuries had finally caught up with him. He had just eight at-bats in 1954, when the Red Sox put him on waivers. The New York Giants claimed him off waivers. But after just 11 at-bats, with only one hit, he was waived by the Giants, only to be picked back up by his old team the Tigers. In January, Hoot was sold to the Baltimore Orioles. He was 34 now, but still wasn’t ready to hang up the spikes. Through the first half of the 1955 season, he was hitting .238 when he was traded to Cleveland. He batted .288 over the rest of the season for the Indians. The next season was his last, but he must have felt as if he were was inside a pinball machine. In May 1956, Hoot was traded from Cleveland back to Baltimore. He drew his final release in October and decided it was now time to stop playing the game he loved. The unemployment line never saw Hoot however. The Indians quickly hired him as a scout and in 1959 was made assistant farm director. Over the next three seasons, he was vice president, assistant to the president, acting general manager of the Indians at various times, before returning to scouting in 1967. In 1970, he returned to the diamond for one season as a coach. Then, in 1971, after 14 seasons with the Indians, he went back to his old team, the Tigers, as the director of player development. Hoot held his front-office position with the Tigers until 1978, when he became a special-assignment scout based in Houston. Hoot Evers passed away after a short illness, at age 69, on January 25, 1991, in Houston. |

|||||