|

|

1923-1929 |

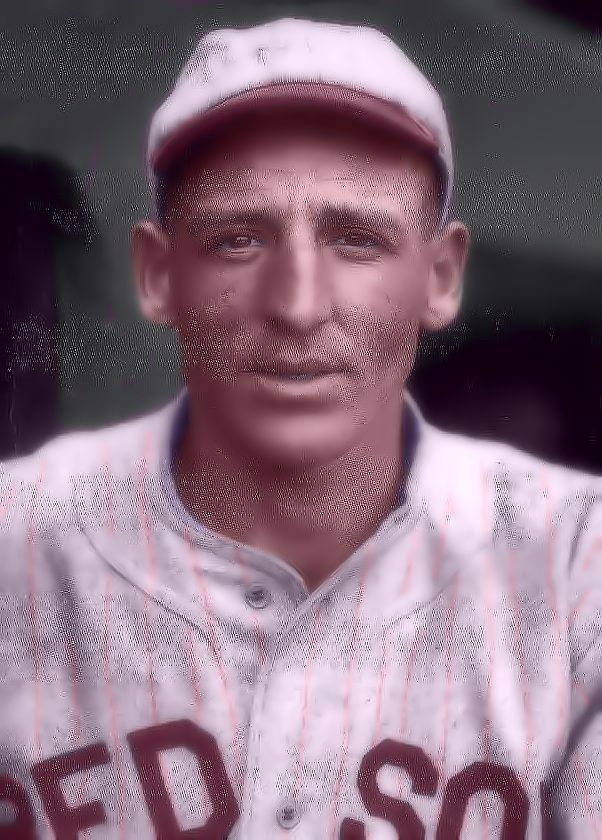

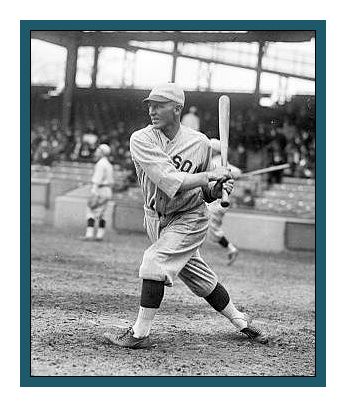

A boxer

turned ballplayer, Ira James “Pete” Flagstead became a 13-year

major-league outfielder who hit .290 over the course of his career, mostly

spent with the Detroit Tigers and Boston Red Sox from 1917 through 1930.

He was raised a long way from the major leagues of the day, in Olympia,

the capital of the state of Washington.

William Flagstead’s father, Thomas, worked aboard boats. Born in 1831, he

came to the United States in time to be included in the 1870 census, which

listed him as a fisherman in Muskegon, Michigan, a sizable city on Lake

Michigan. Ten years later, Thomas was a sailor. It was the profession that

William held in 1900, a sailor on the Great Lakes living in Muskegon with

his wife, Bella, young Ira, and two other sons, Willie (a couple of years

younger than Ira) and Harold, three years younger than Willie. A daughter,

Dorothy, was born after Willie. According to the 1910 census, Bella worked

as a servant for a private family.

In Muskegon, the family lived across the street from a baseball field and

it’s not surprising that by the age of 16, Ira was the catcher on the

Muskegon Independents town team. A degree of wanderlust took him west,

setting out with a suitcase but without a plan and he wound up in the

Northwest, working in a lumber mill in Littlerock, Washington. He later

moved to Olympia to work in a mill and then as a steamfitter.

In the Washington capital, Ira was the catcher for the Olympia Senators

beginning in 1913. He’d been offered a tryout with Seattle

but declined, since the pay was less than he was making.

Ira registered for the draft in World War I in May 1917. He was working at

the time for the Marlin Hardware Company in Olympia, as a steamfitter.

That same year, he began his baseball career. But it had been boxing that

first caught his fancy. He worked with a 20-pound sledge hammer in the

foundry and he was almost 25, feeling fit and tough. He’s listed as

5-feet-9 and weighing 165 pounds when he played baseball – stocky. But he

weighed a lot less as a teenager, and it was as a lightweight (130-135

pounds) that he first climbed into the ring at Lacey, Washington. Stepping

into the ring to fight him was a so-called “lightweight” who may have

weighed 175. According to an undated, unattributed news clipping found in

Flagstead’s player file at the Hall of Fame, it was at that moment that he

decided he was going to quit boxing. But first he had to fight:

The battle started. Ira shed his fist off the face of the opposing

“lightweight” so often that it looked as if it were raining boxing gloves.

He bounced ’em off the body of this giant so fast that it sounded like

the rataplan of gunplay. But the lummox was big. He was tough. He cast off

punches like a duck shakes water. He stayed through the entire 15 rounds.

Then the referee, who resembled justice only in that he was blind, said

‘draw.’

Flagstead turned instead to baseball and became a catcher on the foundry

ball team. “Flaggy” was good, and he came to the attention of Frank

Raymond, the manager of the Tacoma Tigers, a Class B team in the

Northwestern League. It was May 1917. He started out batting so well that

another ballclub took immediate notice: the Detroit Tigers. It was former

White Sox catcher Billy Sullivan who signed him. Sullivan was working for

Detroit and had come to scout Herm Pillette. He saw Tacoma beat Seattle in

14-inning game, 2-1, with Flagstead driving in both runs. Sullivan paid

$750 for his contract and reported to Detroit on July 17.

Flagstead debuted with the Tigers on July 20, coming into the game to hit

for right-fielder George Harper in the seventh and playing through the

ninth (a 3-1 loss to the Yankees), having two at-bats but no hits. He

appeared in four games in 1917, collecting four at-bats without a hit and

striking out once. He played in parts of two games in the field, but

handled no chances. It was back to Tacoma and by the end of the year he

had played in 56 games for Tacoma as an outfielder, hitting an impressive

.376, fourth best in the league. He was eagerly anticipated in

Chattanooga.

In 1918, Flagstead started the season playing first base and batting third

for the Chattanooga Lookouts in the Southern Association, doubling and

scoring in the ninth inning of the opener, against the Atlanta Crackers.

The season was more of the same

� a league-leading .379 average,

although only in 49 games in this war-shortened season. Contemporary

sources say he hit .381. He joined the artillery at Camp Custer, Michigan,

rising to the rank of sergeant first class. His unit was due to deploy

overseas when the armistice was signed. He was discharged on January 27,

1919

In 1919, Flagstead joined Detroit for the season. The Tigers had enough

catching, so he was tagged for outfield work by manager Hughie Jennings.

It was thought that he might have a very good season, and he didn’t

disappoint, starting off with two singles and a double in his first game,

on April 26.

Flagstead came batted .331 and walking 35 times (plus getting hit seven

times) for an on-base percentage of .416. He had a little power, better

than average for the era, with five home runs. His .331 average was fifth

in the American League as was his on-base percentage (ranking above him in

the league’s top five were Ty Cobb and Bobby Veach.) His slugging

percentage placed him sixth. As early as the turn of the year, news

stories began to mention that Red Sox owner Harry Frazee had his eyes on

Ira. (See, for instance, the

Boston

Globe of January 9, 1920.)

He experienced the proverbial sophomore slum in 1920, his average

plummeting to .235. Detroit added a proper shortstop in Topper Rigney, who

also hit .300, and another reserve outfielder in Bob Fothergill.

Consequently, Flagstead played only half as much in 1922 as he had in

1921, just 44 games, and hit .308. The Tigers just had so many superb

ballplayers, particularly in the outfield slots, that they had a .300

hitter as a utility player. Flagstead did have the opportunity to play a

pretty full year in 1923, but it was mostly for the Boston Red Sox. He’d

gotten in one pinch-hit at-bat with the Tigers on April 24, four days

before he was traded. When the trade happened, on April 28, it was

Flagstead for Ed Goebel, also an outfielder, who never appeared in a game

for either Boston or Detroit.

For Boston, manager Frank Chance had Flagstead take over the lion’s share

of the work as the team’s regular right fielder (filling in a lot for

Shano Collins), and Ira hit .312 in 109 games with a career-high eight

home runs. Only left-fielder Joe Harris hit more. It was the first of six

full seasons he played for the Red Sox, some of the worst seasons in Red

Sox history. The team was so deep in the cellar that it hardly ever saw

the light of day. Yet Flagstead averaged .295 in 2,941 Boston at-bats and

drove in 299 runs.

He made a good impression from the start, hitting a home run in his debut

on May 10, but the White Sox beat the Red Sox, 9-7. One of the bigger RBIs

came on September 14, in the game in which Red Sox first baseman George

Burns pulled off an unassisted triple play. Flagstead made “several

wonderful catches” in right field, and the hard-fought game with the

Indians went into extra innings tied 2-2. Cleveland took a 3-2 lead in the

top of the 12th, but Flagstead came up with the bases loaded in the bottom

of the 12th and hit a “sizzling drive” to left field which scored the

tying and winning runs.

Except

for 1923, Flagstead played center field almost exclusively from that point

on. There was one disappointing day, when his errant ninth-inning throw on June

5 cost the Red Sox the ballgame. But his 31 outfield assists led the league in

1923, as did his 24 in 1925. He was a bit of a reckless outfielder, it seems,

crashing into walls. A bit of hyperbole, of course, but none other than Babe

Ruth claimed that Flagstead deprived him of as many as 10 home runs a year.

Flagstead was living in Littlerock, Washington, as 1924 began, and made his way

to San Antonio for Red Sox spring training, arriving on the evening of March 14

and reporting to manager Lee Fohl. His place in center field was secure and he

did nothing to jeopardize the status. He played in 149 games in 1924, hitting

.307 (with a .401 on-base average), tapped as Boston’s leadoff hitter. He drove

in 43 runs, but scored 106, by far tops on the team. August 20 was his best day;

his four hits (including a double and triple) figured in three runs of Boston’s

5-4 win over the Indians, as did at least one sensational shoestring catch in

the field.

During

the offseason, back in Washington state, Flagstead had one of his brothers pitch

to him using cheap, nonregulation baseballs – because they were a bit smaller

and therefore trained his eye better. He was reported in good physical shape

just one day after arriving at spring training, and it paid off: he appeared in

148 games, though he tailed off in average (.280, after five straight seasons

hitting above .300). He drove in 18 more runs than in

�24 but

scored 22 fewer. His eye was in fine shape on May 8, however, when he was

1-for-1 in a game but scored five runs (he walked five times.) Part of the

problem with his average followed Flagstead’s being beaned by Benny Karr of the

Indians on May 14. He was hitting .323 at the time and missed only a few games,

but he rarely hit as high as .300 again.

Flaggy set a record on April 19, 1926, in the second game of the Patriot’s Day

doubleheader against the visiting Athletics, by taking part in three double

plays in one game, all from center field. July was not a good month, though. He

was suspended indefinitely on July 12 for something he’d said in a prior game to

Umpire Harry Geisel (he was back by the 15th, however), and then he suffered a

broken collarbone on July 31 making a diving catch of a low liner, and was out

for the rest of the season. He’d hit .299 and was on track for his fourth year

in a row of solid baseball.

Flagstead reached base 37.4 percent of the time in 1927, batting .285, and hit

.290 in 1928, playing in 131 and 140 games respectively. He was reliable and

steady, though at age 33 and 34, his average had tailed off.

He was a popular player in Boston at a time when the team offered little to

attract fans. A July 26, 1928, column in

The Sporting

News persuasively made the case: “He is one of the reasons why the

fans here have always been so patient with the Red Sox. It is not so easy to

razz and rough ride a ball club which has the hustling, sincere Pete Flagstead

playing center field.” Fans had held a “day” for Flaggy on July 21, and he was

presented with $1,000 in gold and an automobile. “Harry Hooper was never more

popular than Flaggy in Boston, and that’s saying quite a mouthful because there

have been few players anywhere who have such a degree of popularity as Hooper

enjoyed here for years.” The car came in handy, given Flagstead’s residence in

the Northwest and his love of driving. He also enjoyed sightseeing in the cities

he visited, often taking tour buses and visiting sights like the Bronx Zoo and

the Smithsonian.

In 1929, the Red Sox were ready to go with Jack Rothrock in center field and so

floated the 35-year-old Flaggy on waivers early in the season (even though he

was hitting over .300 at the time). He was claimed by the Washington Senators on

May 25.

There was one more year of baseball in Flagstead’s future, though. He played in

the Pacific Coast League for Seattle and Portland in 1931, hitting .231 in 68

games. It was time to move on. Flagstead returned to Washington, where he and

his wife Reita enjoyed fishing and raised game roosters and English call ducks.

He played more leisurely ball in Olympia, and had the talent to help land his

Timber League team in the playoffs three years in a row. He was recognized by

both his birth state (in the Muskegon Area Sports Hall of Fame) and his adopted

state (Washington Sports Hall of Fame).

Flagstead took ill in August 1939 and died in his sleep the following March 13

at the very young age of 46.

|