|

|

1938-1944 |

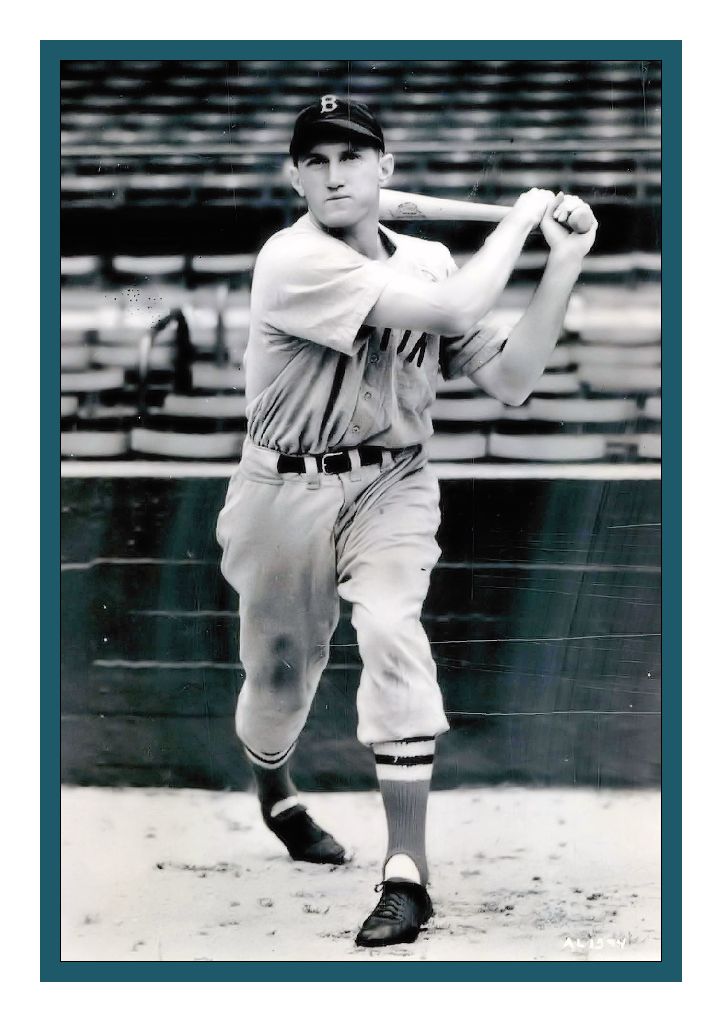

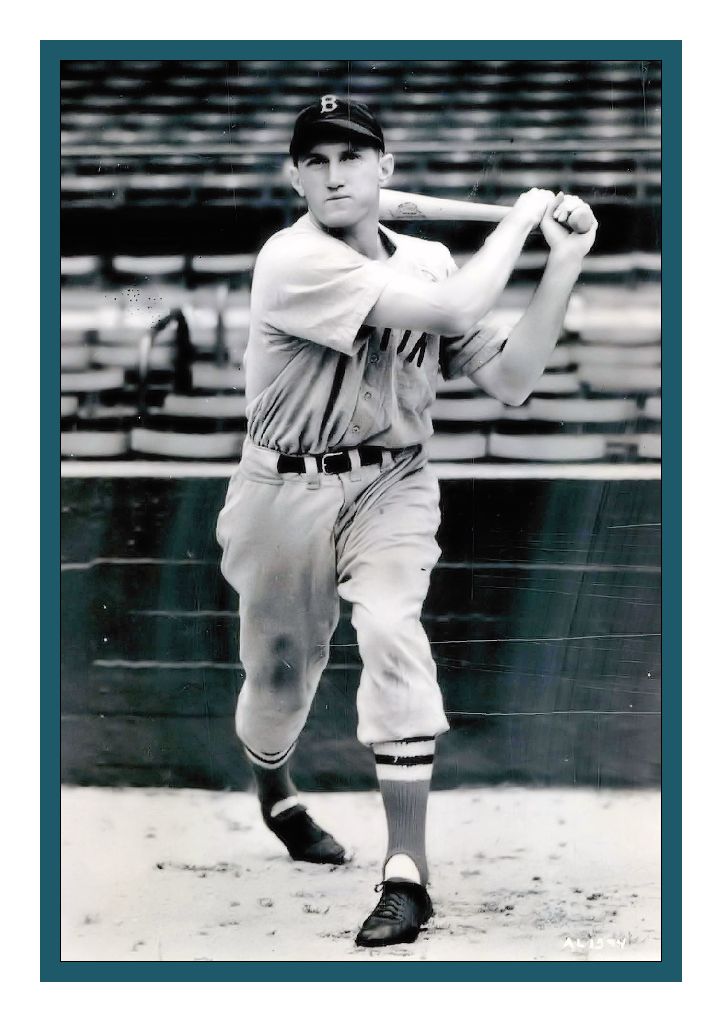

Jim “Rawhide” Tabor was a five-tool player before that phrase became part of the

baseball vernacular. He was 6-feet-2 and played at 175 to 185 pounds. Often

described as raw-boned and rangy, he hit from the right side for average and

with power. He had great speed, was Mercury-quick, and had a terrific throwing

arm. Tabor’s arm was the standard by which all other infielders’ arms were

measured in the 1940s. When Red Sox first baseman Jimmie Foxx was accused of

having an illegally reinforced glove, he pointed at third baseman Tabor as his

defense. “He throws the ball like a cannon shot,” Double-X asserted.

Unfortunately, cannon shot turned to scattershot all too often. Tabor wasn’t

always quite sure where the ball was going when he let loose.

Tabor earned his moniker with his hustle, his win-at-any-cost attitude, and his

toughness. “He’d slide into second and knock you on your ass,” said teammate

Tony Lupien. Catchers blocked the plate at their peril. He once collided so

violently with Detroit’s Joe Hoover that the unfortunate Tiger infielder passed

a kidney stone on the spot. Rawhide was not above upbraiding his

teammates. Early in Tabor’s career, Lefty Grove came over to third to berate

Tabor for an error the young third sacker had made. Tabor did not back down to

the veteran Grove. “You’re hired to pitch,” he said. “I’m hired to play third

base. Get out there and pitch.” Ol’ Mose went back to the hill. Tabor had to be

pulled off Minneapolis Millers teammate Ted Williams after one game in which

Williams chose not to go after balls hit to left field. Rawhide also earned his

nickname off the field. Tabor was suspended several times in his career and in

trouble countless other times. The usual reason given for suspension was

“breaking training rules.” Tabor liked the ladies, liked to smoke cigars (he

usually had the stub of a cigar in his mouth off the field), and he liked to

drink. Red Sox outfielder Doc Cramer said, “Jim Tabor was a twister. He would

drink, get drunk and be half-drunk when he came to the park.” The Red

Sox even hired two private detectives to follow Tabor in an effort to get him to

stop drinking. It didn’t work. Jim Tabor had great talent and an undeniable will

to win, but the wax melted quickly for this baseball Icarus.

James Reubin Tabor was born on a farm a mile south of Owens Cross Roads,

Alabama, on November 5, 1916, the second son of John H. and Amy Olene Tabor.

John Tabor was a schoolteacher who once had a contract to play in the Southern

League but gave it up to get married. John imparted his baseball knowledge to

all of his sons. The Tabor troupe played together on an amateur team in Owens

Cross Roads, playing surrounding town teams with “Pop” Tabor as the

manager-catcher and a Tabor boy on first, second, and third base. The third

baseman, Jim, was “the mightiest hitter ever seen down Owens Cross Roads way.”

Jim was also a standout baseball and basketball player at New Hope High School

in New Hope, Alabama. He attracted the attention of University of Alabama

basketball coach Hank Crisp. Tabor received a full four-year scholarship to play

for the Crimson Tide, the first incoming freshman to receive such an award. In

the summer of 1935, after high school graduation, Jim played for the Ozark,

Alabama, nine in the Dixie Amateur League, and soon impressed major-league

scouts. Tabor entered the university in the fall of 1935 and starred on the

freshman basketball team, but when the baseball coach learned he was an

accomplished baseball player, he made sure Tabor went out for baseball as well.

After classes were over in 1936, Tabor played in the semipro Coastal Plain

League in North Carolina. His first assignment in that league did not last long.

Tabor and his manager did not get along and Tabor was dropped from the team. His

university came through with another assignment, Ayden, in the same league.

Tabor thrived there and impressed the major-league scouts again. The

Philadelphia Athletics were first to act, and scout Ira Thomas had Tabor all but

persuaded to join his team, having Connie Mack send a contract and a $3,500

bonus check to Tabor. In the meantime, either Alabama baseball coach Happy

Campbell or football coach Frank Thomas, or both, contacted people they knew in

the Red Sox organization. The Sox promptly dispatched Billy Evans, the head of

the Red Sox farm system, to Alabama with a blank check. Evans signed Tabor with

a $4,000 bonus and was savvy enough to get dad’s signature too (something the

Athletics failed to do). Later the Athletics protested the signing but

Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis ruled in favor of the Red Sox. The Red Sox deal

called for Jim to become a professional after he graduated from college, but

young Tabor couldn’t wait. He had difficulty focusing on his studies and by the

spring of 1937 he was on the phone with Billy Evans. Evans tried to persuade

Tabor to stay in school, but Jim would not be dissuaded. He prevailed and the

Red Sox assigned him to the Little Rock Travelers in the Southern Association.

The 1937 edition of the Little Rock club, managed by former Red Sox third

baseman Doc Prothro, was destined to finish in first place (97-55) and win the

league championship in the postseason playoffs. Tabor was a key ingredient in

the team’s success. Prothro thought the Southern Association too big a jump for

a kid with only a year of freshman ball under his belt, but Evans was sold on

Tabor, and Tabor’s enthusiasm swung Prothro around enough to get Tabor a look. Prothro

needn’t have worried. Tabor showed he belonged from the beginning. Possibly all

the questions were answered early when the Cleveland Indians came to Little Rock

for an exhibition game that spring. On the mound for the Tribe was 18-year-old

star-in-the-making Bob Feller. The first time Tabor faced Feller he struck out.

The next time, Tabor came up with the bases full. He timed one of Feller’s

storied fastballs and laced it for a home run to center field. Jim enjoyed

national publicity for his grand slam off the future Hall-of-Famer.

Tabor stayed with Little Rock all season and was hitting above .300 for most of

the year before finishing at .295. He impressed with his 94 RBIs, 93 runs, 25

doubles, 10 triples, 4 home runs, and 12 stolen bases. The once reluctant Doc

Prothro was now a true believer. He predicted major-league stardom for Tabor.

For his efforts, Tabor was invited to Red Sox spring training in 1938. Tabor

arrived late to camp and did not have much of an opportunity to show his skills.

Once he arrived and started to play a little, he pushed Red Sox third baseman

Pinky Higgins into raising his game. Though Tabor had a good spring, it was

clear he needed more experience. Tabor made the team’s decision easier by

breaking training rules. On April 1 he was optioned to Minneapolis of the top

tier American Association.

Tabor had an excellent year for the sixth-place Millers. He started off quickly,

hitting .452 in early series against Indianapolis, Louisville, Columbus, and

Toledo. He was the early league leader in triples by “combining a ground-eating

stride with a penchant for belting liners to left and right center.” He drove in

six runs in a game in the early going and by June 9, he had already hit two

game-winning homers.

When Pinky Higgins injured his knee in late July, Tabor, who was hitting .330

with 13 home runs and 72 RBIs in 103 games with the Millers, was called up to

Boston. Tabor made his major-league debut in Cleveland on August 2, going

2-for-4 with two doubles, both off Denny Galehouse. By August 8, the Red Sox

coaching staff was predicting Tabor would be better than the Indians’

sensational third baseman, Ken Keltner. Joe Cronin, who claimed he

was not that impressed with Tabor in spring training, said he couldn’t believe

how much the rookie had improved. Cronin favorably compared Tabor’s defense at

third base to that of his old Pittsburgh teammate Pie Traynor. Expectations were

high, but Tabor did not disappoint. On August 9, the Red Sox were at Shibe Park

in Philadelphia for a three-game series. Athletics starter Nels Potter was

perfect through six innings and had a 3-0 lead, but the Red Sox exploded for

seven runs in the seventh. The big blow was a grand slam by Tabor, his first

major-league home run. Higgins soon recovered from his injury and Tabor was to

be sent back to Minneapolis, but American Association rules prohibited the move.

Consequently, Tabor remained with the Red Sox through the end of the season. He

was relegated to pinch-hitting and the occasional start. His teammates voted him

a half-share of the 1938 second-place money. Overall, Tabor got into 19 games

for the Red Sox in 1938 and hit .316 with one home run and eight RBIs. He showed

well enough to cause a “problem” for Joe Cronin.

The problem was a “good” problem. The Red Sox had two good third basemen, Tabor

and Higgins. The incumbent, Higgins, 29, was coming off two successful years

with the Red Sox. He had been a consistent run producer since 1930, when he was

with the Athletics. Tabor was only 21 at the end of the 1938 season with just

two years of professional baseball on his résumé. It seemed risky to many Red

Sox fans and the media to trade Higgins, but that is exactly what the Red Sox

did.

Citing the dire need for pitching, on December 15, 1938, the Red Sox traded

Higgins and pitcher Archie McKain to Detroit for pitchers Elden Auker and Jake

Wade and outfielder Chet Morgan.

Tabor was impressive in spring training. The confidence he gained from knowing

the third-base job was his must have been palpable. Time and again, his arm was

described as the strongest in baseball, often with the “erratic” qualifier. He

was enthusiastic about baseball regardless of the conditions. Many baseball

experts predicted Tabor would eventually take his place among the great third

basemen of the time. By the time the 1939 season started, there were few who

thought Tabor was a gamble.

The Red Sox opened the 1939 season on the road at Yankee Stadium. The game

matched future Hall of Famers Red Ruffing and Lefty Grove. Tabor, batting fifth,

went 1-for-4 with a double in his first game as the Red Sox regular third

baseman and played errorless ball as the Yankees won, 2-0. Tabor went 4-for-5 on

April 24 against Washington. On the 25th, he singled to knock in Jimmie Foxx in

the ninth to tie the game, and Foxx homered in the 11th to win it. On

May 16, Tabor went 3-for-5 with five RBIs, and three days later he had a 4-for-4

day. On May 21, he went 2-for-3 with two runs scored and an RBI. While certainly

not perfect, Tabor was more than holding his own in the early going.

By the end of June, however, Joe Cronin suspended Tabor for three days. Tabor

“foolishly broke training much after the fashion of a high school boy who wanted

to show off.” Tabor was back in the lineup against Philadelphia on June 29. On

July 1 against the Yankees, he went 2-for-3 with a run scored and two stolen

bases. He had a “mad plunge for a run in the third” and spiked Yankee catcher

Buddy Rosar, who was blocking the plate. Rosar had to leave the game and was

admitted to a hospital.

Tabor had the game of his life on July 4 in Shibe Park. The Red Sox swept the

A’s in the holiday twin bill by scores of 17-7 and 18-12. Tabor was just getting

warm in the opening game when he went 3-for-5 with a home run, a double, and two

RBIs. In the nightcap, Jim Tabor had a record-tying performance. He came up with

the bases loaded in the third facing A’s starter George Caster. Tabor, who had a

grand slam in Philadelphia the previous August, enjoyed Shibe Park one more time

with a long ball off Caster. In the sixth, the bases were full again for Tabor

and he hit an inside-the-park grand slam off Lynn Nelson. He touched Nelson

again for a solo shot in the eighth to top off his nine-RBI game. Tabor was only

the second major-league player to

hit two grand slams in a single game.

The four home runs in a doubleheader also tied a record. The next day, Tabor hit

another home run against A’s pitching for his fifth home run in three games.

Rookie Jim Tabor had a good year at the plate. He finished at .289 with 33

doubles, 8 triples, and 14 home runs in 149 games, while leading the Red Sox

with 16 stolen bases. His 95 RBIs nearly replaced the 106 produced by Pinky

Higgins the previous year. Tabor’s power/speed number was fifth in the league.

His fielding was more of a mixed bag. He had 40 errors, the most by any third

baseman in the major leagues that season, though tempered by his 338 assists,

also the most in either league. He was making more errors, mostly throwing, but

he was getting to more grounders than anyone else.

Tabor started the 1940 season slowly, but broke out of his slump after about a

dozen games. On May 3, he hit two home runs against the St. Louis Browns; the

second tied the game in the ninth. In the 10th, Tabor singled with

the bases loaded for the walk-off win. On June 1, Tabor knocked himself out in

batting practice. He hit down on a ball that bounced back and hit him in the

eye, cutting him badly enough for him to need two stitches. Rawhide missed the

game that day but he was back the next.

On Sunday, July 14, the Red Sox had a doubleheader at home against the Browns.

Tabor played in both games and went 4-for-8 with a double, three RBIs, and a

stolen base. The Sox won both games. Some time after the second game, James

Tabor married Bostonian Irene Bryan at St. Augustine’s Church in Boston.

Teammate Joe Heving was the best man. Shortly after the wedding, Tabor went on a

home-run tear, hitting four in three games between July 23 and July 26. (He hit

another on July 28.) Tabor had eight RBIs in the three games, going 6-for-12. He

had six hits in six plate appearances over the course of two games, July 25 and

26.

While opposing pitchers couldn’t stop Tabor, his appendix did. Before a game

against Cleveland at Fenway Park on August 21, Tabor collapsed on the field and

was taken to the hospital for an emergency appendectomy. He was expected to be

out a month. On September 21, precisely one month later, Tabor was back in the

lineup and went 3-for-4 with an RBI. The Red Sox were 12-16 with Tabor out of

the lineup and were eliminated from the pennant race. Tabor, part of a

power-hitting infield that hit 103 home runs, had career highs that season in

home runs (21) and slugging percentage (.510). He hit .285 in 120 games with 28

doubles, 6 triples, and 14 stolen bases. He was second only to the Yankees’ Joe

Gordon in the power/speed category. He also improved in the field. He still had

the most errors (33) in the American League, but his range factor35

was the best in the league, up from third best the previous year.

Tabor, who had no lasting effects from the appendectomy, put on 10 pounds in the

offseason and told

The Sporting

News he wanted to add five more (Joe Cronin had been trying to get

Tabor to put on weight for at least the last two seasons). The new, bulkier

Tabor got into trouble with Cronin early in spring training of 1941.

On March 21, 1941, the

New York

Herald

Tribune reported that Tabor had been suspended indefinitely for

repeated violation of training rules. Tabor did not let the spring training

problems faze him, however (or maybe the suspension got his attention), because

he had a great first half of the season. By July, he was hitting 30 points

higher than any other AL third baseman. By year’s end, Tabor’s average had

dropped off to .279, but he had a career high in RBIs with 101 in just 125 games

(injuries curtailed his playing time). He also had a career-high 17 stolen

bases, fifth best in the league. Tabor had 16 homers, 29 doubles, and 3 triples

for the second-place Red Sox. After a few weeks in the South, Tabor spent the

winter in the Boston area working for the Gillette Safety Razor Company.

Though the Red Sox improved to 93 wins in 1942, Tabor’s hitting and fielding

dropped off. He was benched for a time because of a prolonged slump. He hit just

.252 in 139 games, and all his power numbers were down: 12 home runs, 18

doubles, 2 triples, and 75 RBIs. He had just six stolen bases and was caught 13

times. In the field, he had 33 errors to lead all American League third sackers;

his range, which had been a strength, was now diminishing. It appeared his hard

living was catching up to him. Tabor spent the winter in Boston again. He and

his wife purchased a home in East Milton and Jim worked as a riveter at the Fore

River Ship Yard in Quincy. Tabor was able to work out at Tufts University often

in the winter and reported early for spring training there (wartime travel

restrictions barred spring training in the South).

Tabor started the 1943 season poorly, hitting just .158 through April 29. By May

he was benched for poor hitting, and he hit just .243 through June 24. The

season proved to be difficult for the Red Sox. Jimmie Foxx had retired and

Williams, DiMaggio, and Pesky were in the military. The Red Sox finished

seventh. Tabor finished the season at .242 in 137 games, his lowest average as a

professional. His slugging average was just .299. Tabor committed 26 errors, a

career low, in 133 games at third, but still high enough to lead the league for

the fifth consecutive year.

The Red Sox held spring training at Tufts again in 1944. Manager Cronin told

players who lived in warm-weather states to stay home and train on their own.

Consequently, Tabor, who had again spent the winter in Boston working at the

shipyard, was one of only four players to attend early spring training. His

batting average and the Red Sox’ fortunes bounced back a bit in 1944. Tabor was

hitting .296 as late as July 27. On August 10, he passed his military

pre-induction exam, making him eligible for call-up to the Army at any time. He

was allowed to finish the season. Tabor finished the year with a .285 average in

116 games. He had 25 doubles, 3 triples, 13 home runs, and 72 RBIs. On October

26, Tabor got the call from Uncle Sam. He entered the Army at Fort Devens,

Massachusetts. He spent the remainder of 1944 and most of 1945 at Fort Devens,

then at Camp Croft, South Carolina.

Tabor was given a dependency discharge from the Army on December 14, 1945, and

was ready to rejoin the Red Sox for the spring of 1946. The Red Sox looked like

serious contenders for the American League pennant with Williams, DiMaggio,

Pesky, Doerr, and Tabor set to return to their lineup. The Red Sox did win the

1946 flag, but Jim Tabor was not part of the team. Joe Cronin and general

manager, Eddie Collins thought Louisville third baseman Ernie Andres was ready

for the big time and thought Tabor expendable. On January 22, 1946, after he

cleared military waivers, the Red Sox sold Tabor’s contract to the Philadelphia

Phillies for a reported $25,000. In 806 games with the Red Sox, Tabor had hit

.273 with 90 home runs and 517 RBIs. Sportswriter Burt Whitman had these parting

comments: “[H]e looked like a sure-fire big league star. He was very fast, had

power at bat and while erratic of throwing arm, appeared to be about ready to

blossom into stardom at any time. Annually, he failed to live up to this

promise.”

Tabor’s health and perhaps his fitness were becoming a concern. In late October

or early November, Tabor visited the Lahey Clinic in Boston for an unspecified

ailment. There were more injuries, specified and otherwise, during the spring

and summer of 1947. He had sore ankles in spring training and was in Temple

University Hospital for X-rays and “further probing of his tonsils.” He had a

bad spine bruise between the shoulder blades caused by an overly exuberant

trainer. He injured his hip sliding into a base.

On December 11, 1947, the Phillies traded for outfielder-first baseman Bert Haas

of the Cincinnati Reds. In early January 1948, they announced Haas would be

their third baseman for the coming season. In late January it looked as though

Tabor might be dealt to another team. When he wasn’t, it appeared doubtful he

would be invited to the Phillies’ camp in Florida. In the end, Herb Pennock left

it up to manager Ben Chapman. The former Red Sox outfielder allowed Tabor to

come to camp to compete for the position. Tabor did not earn the job, however,

and was given his unconditional release on March 2.

On August 17, 1953, Tabor suffered a heart attack. He remained unconscious and

in an oxygen tent until August 22, when he succumbed to congestive heart

failure. Jim “Rawhide” Tabor was just 36 years old.

|