|

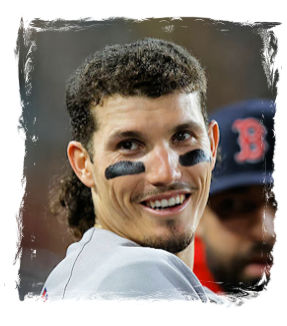

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||

Jarren Duran was born September 5, 1996 in Corona, California, and attended Cypress High School in Cypress, California. He went on to play three seasons of college baseball at California State University, Long Beach, where he was primarily a second baseman. In the summer of 2017, he played collegiate summer baseball for the Wareham Gatemen of the Cape Cod Baseball League. The Boston Red Sox selected Duran in the seventh round of the 2018 MLB Draft. He began his professional career in 2018 with the Lowell Spinners and Greenville Drive, batting a combined .357 across both levels. In 2019, he opened the season with the High-A Salem Red Sox before being promoted to the Double-A Portland Sea Dogs on June 3rd. That year, he was added to Baseball America’s Top 100 prospects list, ranked No. 99, and was selected to the 2019 All-Star Futures Game. He was named High-A "Player of the Year" by Baseball America and Red Sox Minor League"Baserunner of the Year" in 2019. Across 132 games between Salem and Portland, he hit .303 with five home runs, 38 RBIs, and 46 stolen bases. He was invited to major league spring training in 2020, but the minor league season was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic, so he played winter ball for Criollos de Caguas in Puerto Rico that offseason and was named MVP of the final series, helping the team win the league championship. Jarren began the 2021 season with the Triple-A Worcester Red Sox and was promoted to the major leagues on July 16th. He debuted the next day against the New York Yankees, recording a hit in his first at-bat off Gerrit Cole. Three days later, he hit his first MLB home run against Ross Stripling of the Toronto Blue Jays. He appeared in 33 games n 2021, hitting .215 with two home runs and 10 RBIs. In 60 games with Worcester, he hit .258 with 16 home runs and 36 RBIs. Jarren split time between Worcester and Boston during the 2022 season. He appeared in 58 major league games, batting .221 with three home runs, 17 RBIs, and seven stolen bases. Despite flashes of his speed and potential, his season was marked by inconsistency and a few high-profile mistakes, including losing a fly ball in Fenway Park that resulted in an inside-the-park grand slam against Toronto on July 22nd. He also spent time on the restricted list due to vaccination requirements and was later vaccinated to rejoin the team in Toronto in September. He began the 2023 season in Worcester but was called up on April 17th following an injury to Adam Duvall. He quickly became an everyday player, ranking among MLB leaders in doubles and stolen bases. Over 102 games, Jarren hit .295 with eight home runs, 40 RBIs, 24 stolen bases, and 34 doubles (seventh in MLB at the time). His season ended prematurely after suffering an injury on August 22nd, requiring surgery and landing him on the 60-day injured list. Before the 2024 season, manager Alex Cora named Duran the team’s leadoff hitter, a role in which he thrived. He was selected to the 2024 MLB All-Star Game and earned All-Star Game MVP honors after hitting a go-ahead home run that secured the American League’s victory. Duran delivered a career-best season, leading MLB in plate appearances (735) and at-bats (675). He also led the majors with 48 doubles, tied for the lead with 14 triples, and posted a .285 BA with 24 home runs, 75 RBIs, 111 runs scored, and 24 stolen bases. He finished 8th in American League MVP voting. |

|||