|

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||||

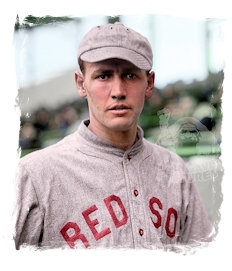

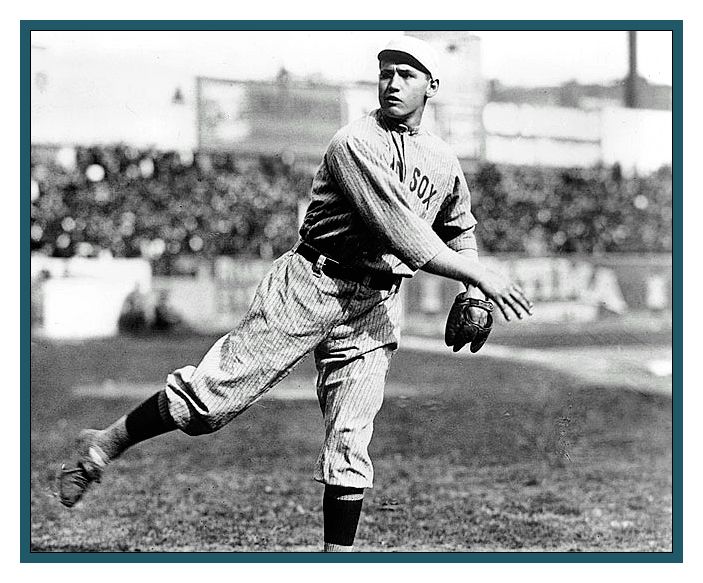

Joe Wood's reign as one of the most dominating pitchers in baseball history lasted a brief two seasons, but it left an indelible impression on those who witnessed his greatness first-hand. "Without a doubt," Ty Cobb later recalled, "Joe Wood was one of the best pitchers I ever faced throughout my entire career." In 1911 and 1912, Smoky Joe Wood won 57 games for the Boston Red Sox, including a no-hitter against the St. Louis Browns on July 29, 1911, and an American League record-tying 16 straight wins in the second half of the 1912 campaign. He was by no means large or overpowering, standing 5'11 3/4" and weighing in at 180 pounds, but concealed in his lanky frame was one of the most overpowering fastballs of the Deadball Era. Walter Johnson could only agree. "Can I throw harder than Joe Wood?" he asked a waiting reporter. "Listen, mister, no man alive can throw harder than Smoky Joe Wood." Howard Ellsworth Wood was born in Kansas City, Missouri, on October 25, 1889, the second son of John and Rebecca Stevens Wood. The nickname by which he would be known for the rest of his life came to Howard by way of two circus clowns named Petey and Joey. With Pete Wood preparing to enroll at the University of Kansas, Joe -- schooling now a thing of the past -- passed the time working odd jobs and playing ball. As the close of the 1906 season approached, baseball fans in Ness City learned from posters pasted on storefronts across town that the Ness City Nine was slated to take on an unusual opponent, the National Bloomer Girls out of Kansas City. Though they advertised themselves as an all-girls team, the popular bloomers outfit routinely augmented their strength by adding young boys, "toppers" as they were known, to the roster. Joe sparkled in a 23-2 trouncing of the visitors that afternoon, and at the close of the contest Bloomer owner Logan Galbraith offered him $21 a week to join the team for the duration of the summer. After he closed out the summer with the Bloomers, Joe signed on as an infielder with the Three-I League Cedar Rapids Rabbits, managed by one time Baltimore Oriole Belden Hill. Reportedly "all full up" with infielders, however, in the spring of 1907 Hill unceremoniously scratched Joe from his roster and handed his contract, free of charge, to his friend Jason "Doc" Andrews, manager of the Western Association Hutchinson White Sox. Joe started the season at infield, but weeks into the campaign, the pitching-starved White Sox dispatched Joe to the mound. By late September his uncanny speed caught the attention of numerous scouts, among them George Tebeau, owner of the American Association Kansas City Blues. Tebeau purchased Joe's contract for $3,500 and ordered him to Association Park in Kansas City in March of 1908. Joe's 7-12 record in 24 appearances with the mediocre Blues was nothing to gloat over, but his strong exhibition work against Joe Cantillon's Washington Senators back at spring training and a near perfect no-hitter in Milwaukee on the 21st of May were more than enough to attract big league interest. After a fair bit of contractual wrangling, Joe's contract was purchased by the Boston Red Sox, and on August 24th, 1908, the 18-year-old made his big league debut at the Huntington Avenue Grounds. Joe was bested by Doc White and the Chicago White Sox, 6-4. In the first instance of a pattern that would dog him for much of his career, in the spring of 1909 Joe suffered a foot injury during a hotel room wrestling match with his best friend, Tris Speaker, which knocked him out of action until mid-June. Joe pitched well on his return, notching 11 wins against 7 defeats, and his strong work continued through the first half of 1910. But, once again, injury intervened, this time courtesy of a Harry Hooper line drive to the ankle during batting practice. On a club rife with cliques and infighting, Joe Wood was as rugged as they came. "He talked out of the corner of his mouth and used language that would have made a steeple horse jockey blush," But for the underachieving 1910 Red Sox, Joe's rough demeanor off the field (not to mention his disappointing 12-13 finish) won him no praise among Red Sox brass. Exasperated by his club's disappointing 4th place finish, at the close of the summer Boston owner John I. Taylor announced he had drawn up a list of so-called "malcontents" among his players, and Joe Wood's name, word had it, stood unceremoniously at the top of his list. Weeks later, rumors swirled out of Boston that Taylor was on the verge of shipping Joe, along with battery mate Bill Carrigan, out of Boston permanently. Had Taylor traded Joe -- and given the Red Sox owner's dubious track record, there is no evidence to suggest he was not serious -- he would have single-handedly deprived Boston of one of the most electrifying summers of baseball on record. After nailing down 23 victories in 1911, in 1912 Wood rose to the very top of his game. Pitching in newly opened Fenway Park, he got off to a modest 3-2 start (twice defeated by Clark Griffith's Senators), but by the close of June his 16-3 mark placed him second in the AL to Philadelphia's Eddie Plank. Joe came up short, 4-3, against Plank on July 4th, but from there he was literally unbeatable. On August 28, he tied down his 12th straight win, bringing him to within four of Walter Johnson's record of 16. With the Red Sox bearing down on the pennant in early September, the stage was set for one of the most storied moments of the Deadball Era. "Up until that time Johnson had his sixteenth [straight win] and lost his seventeenth. I had about eleven [actually thirteen]," remembered Joe. "Well, old Foxy Clark Griffith comes in and says, 'Walter Johnson should have the right to defend his record of 16 straight', so he challenged Joe Wood to meet Walter Johnson." On September 6 a circus-like crowd estimated at 35,000 packed every crevice of Fenway Park -- filling the stands, outfield and even foul territory along the right- and left-field foul lines -- and cheered wildly with every strike Joe burned across. One boy, hit by a foul ball behind home plate, had to be carried from the field; another reportedly "fainted from excitement" and had to be escorted form the stands. In the end, Joe prevailed 1-0, a victory made possible when back-to-back fly balls by Tris Speaker and Duffy Lewis (that would have been playable under ordinary circumstances) fell harmlessly into the crowd and were ruled as doubles. Nine days later, Joe tied Johnson's record with a 2-1 victory over St. Louis. On September 20 in Detroit, an error by Red Sox shortstop Marty Krug (in addition to Wood's own mediocre pitching) deprived Joe of a 17th consecutive win, but he bounced back to win his final two starts of the summer to bring his record to 34-5, to go along with a 1.91 ERA and career-bests in innings (344), and strikeouts (258). He went on to win three more games against John McGraw's New York Giants in the World Series, capping his extraordinary summer with a 4-3 win in relief of Hugh Bedient in Game Eight on October 16. In the spring of 1913 Smoky Joe Wood stood atop the Majors. But, once again, he was vexed by injury. The first mishap occurred in Detroit on July 18, 1913, when Joe slipped on the wet grass fielding a Bobby Veach infield grounder along the 3rd base line, breaking his thumb and (with exception of one inning of relief in September) ending his season. Joe was confident about a healthy return to the majors in 1914, but days before he was scheduled to depart for spring training, he was struck by an appendicitis which sidelined him another two months. Wood went on to close out 1914 at a respectable 9-3, and in 1915 he led the AL with a career best 1.49 ERA, in just 157.1 innings of work. To onlookers it was obvious that something was wrong with the erstwhile phenom. Those fears were confirmed in early October when Joe was seen clinging to his shoulder in pain in his final start of the summer, a 3-1 loss to Walter Johnson. He did not factor into Boston's 4 games to 1 World Series victory over Philadelphia two weeks later. Refusing to accept a cut in pay, in 1916 Joe remained at home in Twin Lakes, Pennsylvania, working out at a New York University gymnasium while tending to his ailing arm under the care of New York Chiropractor A.A. Crucius. In February of 1917, his contract was sold to Cleveland for $15,000. At his debut in Cleveland on May 26th, he was shelled by the Yankees in eight innings of work, and three weeks later sportswriters revealed that, in all probability, he was through as a pitcher. The Deadball Era is replete with story upon story of pitchers whose careers were cut short by shoulders torn to shreds; rarely, if ever, did such men make or even contemplate a return to the diamond. Five months after leaving the Indians, however, Joe made the surprising announcement that he intended to attempt a return to the big leagues by converting himself from pitcher to outfielder. In the war-torn summer of 1918 he stepped into Cleveland's starting lineup, hitting a respectable .296 in 119 appearances. From 1919 to 1921 he was platooned with Elmer Smith (his best season coming in 1921 when he hit .366 in 66 games) He enjoyed another strong season with the Indians in 1922, hitting .296 in 142 games, but citing family obligations he opted not to return to baseball for 1923. Over the next quarter century, Joe looked on as his former teammates and adversaries, one by one, won induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, NY. Probably due to his frequent injuries and the fact that his record did not meet the Hall of Fame's requirement that a player's career be "outstanding for a long period of time," the Hall of Fame passed over Wood time and again.

|

|||||