|

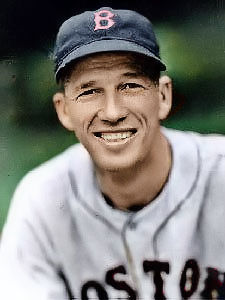

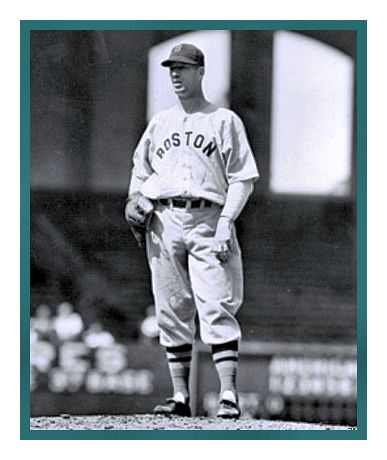

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||||

Robert "Lefty" Grove was grew up in Lonaconing, Maryland. In his spare time, he played a baseball using cork stoppers in wool socks wrapped in black tape, and fence pickets when bats weren’t available. He did not play with a genuine baseball until he was 17, nor genuinely organized baseball until he was 19. With his parents’ blessing, Lefty got a round-trip rail pass and was driven across the mountains in a large car supplied by the Midland baseball team to play. While he was throwing 60 strikeouts in 59 innings for them, word reached Jack Dunn, owner of the International League (Double-A) Baltimore Orioles, who bought Lefty to pitch for his team. In 1920-24, Lefty was 108-36 and struck out 1,108 batters for a minor-league record. By his last season in Baltimore, he went 26-6 and struck out 231 batters in 236 innings. Moreover, he routinely struck out between 10 and 14 major leaguers in exhibition games, including whiffing Babe Ruth in nine times in his eleven exhibition at-bats against him In 1924 Dunn sold Lefty to his old friend, Philadelphia owner/manager Connie Mack, for $100,600. The extra $600 supposedly made it a higher price than the Yankees had paid the Red Sox for Babe Ruth after the 1919 season. Lefty went 10-12 in 1925 and led the American League in both walks (131) and strikeouts (116). Nonetheless, Mack stuck with him. He was only somewhat better in 1926, but he led the league in strikeouts the next five years and won 20 or more games for the next seven. In 1929, the Athletics broke through and won the pennant. When Lefty returned to spring training in 1930 he was as confident as ever and led the league in wins (28), strikeouts (209), and ERA (2.54). In the World Series, the A’s faced the Cardinals and Lefty won the opener, while throwing 70 strikes and just 39 balls and finished 2-1 in the Series, with 10 strikeouts in 19 innings, and a 1.42 ERA. By August in 1931, he was 25-2 for the season and tied for the AL record with 16 straight wins. By year’s end, he was 31-4 with 175 strikeouts and was named the American League’s MVP. The Athletics won the pennant again, this time in a walk at 107-45. In his three World Series (1929 through 1931), Lefty was 4-2, with a 1.75 ERA, 36 strikeouts in 51 1/3 inning. In these same regular seasons, he was 79-15. Stung by poor attendance in the Depression however, Mack was going broke and began unloading his roster. He sold Jimmie Foxx and then Lefty to millionaire Tom Yawkey's cellar dwelling Red Sox. Lefty arrived at the 1934 Red Sox spring training camp, anointed as team savior. Unfortunately, he developed a sore arm in mid-March. In his first appearance in a Sox uniform, he walked the first batter, gave up three consecutive hits and walked the fourth batter, giving up five runs. The great lefty had nothing. He pitched injured throughout the year and went 8-8 with a 6.50 ERA, winning only two of his last five decisions. It was a sad year for a very proud man. At the end of his disappointing season, Connie Mack offered to give Yawkey his money back. Yet Lefty didn’t sour. As wily and ingenious as ever, he spent three weeks at Hot Springs, Arkansas during the offseason, played golf and exercised when it rained. In spring training he found that his arm hurt less when he threw curve balls rather than throwing a fastball. He had thrown the fastball so hard previously that when he threw the curve, it hadn't broke much. Now with a slower arm speed, the curve ball became a weapon. He also learned how to throw the forkball, and so, with a full arsenal of pitches, he proclaimed himself fully recovered for 1935. With his new approach of “curve and control,” Lefty went 20-12 with a league-leading 2.70 ERA. The curve became his major out pitch because he had lost his fastball. Lefty (17-12) pitched well in 1936, but he only struck out 25 batters in his first five complete games. He won his first nine starts, four of them with shutouts, but just couldn't get the breaks to win consistently. The following year, he had another strong season and posted a 17–9 record along with 153 strikeouts. In July of 1938, Lefty fielded a grounder and threw off-balance to first base. A couple of innings later, he had lost the feeling in his fingers and left the game. He was sent to the hospital where the doctors could not get a pulse in his left arm. The doctors decided it was a circulation issue and told him to rest it for a few weeks. He came back and pitched two innings in mid-August at Philadelphia, left with a dead arm and threw his glove against the wall in the dugout. His season was over. He was 7-0 at Fenway Park, but was 14-4 overall. His 3.08 ERA led the team, but his future was in question. Lefty had rested over the winter, returning home to hunt and fish. The doctors had told him that he had to stop using nicotine because it hinders the blood circulation. So he gave up his daily regimen of seven cigars and a can of chewing tobacco. On opening day of 1939, pitching for the first time in a regular season game since last summer, allowed seven hits and only one earned run in a strong eight innings, but lost 2 to 0. The Baseball Museum and Hall of Fame was dedicated followed by a pick-up game that showcased American League and National League stars to dedicate Doubleday Field in June. Lefty pitched to a young catcher named Moe Berg, for the first two innings. In September, Lefty pitched his best game of the season when he four-hit the Detroit Tigers, winning 1 to 0. With runners on second and third and one out in the ninth inning, instead of walking him to load the bases to set up a force play, he pitched to and struck out slugger Hank Greenberg. Lefty had achieved god-like status in Boston. Resurrected from the dead on many occasions, he made 23 appearances with a 15-4 record, leading the league with a 2.54 ERA. It was his ninth ERA title in fifteen seasons. He was their only dependable pitcher but he needed a week before starts. He opened the 1940 season with a two-hit 1-0 shutout in Washington. In June, there was a pregame presentation to honor him at Fenway Park. His tributes began with a dramatized radio program entitled "Highlights in the life of Lefty Grove". Then his family, along with Boston mayor, Maurice Tobin, and Will Harridge, President of the American League, were there to honor him. At night he was honored by all his teammates with a banquet at the Copley-Plaza hotel. Lefty was injured most of the season and his effectiveness was near an end, but with a team best 3.99 ERA and a 7-6 record, he ended the season with 293 wins and no one doubted he’d reach 300 next season. Before the season started, Tom Yawkey had invited Lefty to come down to his estate in South Carolina on their annual hunting trip. With his car packed and ready to head home, Yawkey asked him about his unsigned contract for the upcoming season. Lefty didn't care and signed a blank contract, telling Yawkey to pay him whatever he wished. In 1941, all of baseball was watching Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak before seeing Ted Williams hit .406. In early July, Lefty pitched well but lost 2 to 0 to the Tigers and remained stuck on 299. He gave it another try in Chicago the day after Joe's streak was halted. He should have gotten the win, but the Red Sox defense, let him down. Quietly, he finally became a 300-game winner on July 25th, had earned his place in history and decided to retire. Lefty Grove was one of baseball’s greatest all-time pitchers. No one matched his nine ERA titles. After winning 111 games in a minor-league career, he led the American League in strikeouts his first seven years and starred in three World Series. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1947, his first year of eligibility.

|

|||||