|

1939-1942,

1944-1945 |

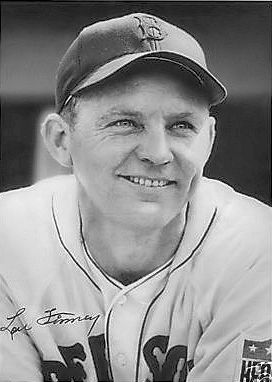

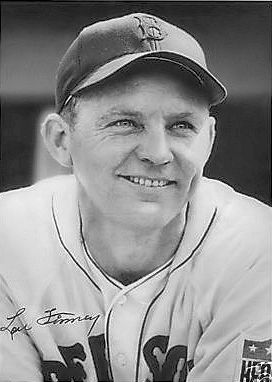

Lou

Finney was a tough man to strike out. A fast, feisty left-handed hitter

with line-drive power, Finney made contact often enough and was versatile

enough in the field to play an important role first for Connie Mack's

Depression-era Philadelphia Athletics and later for Joe Cronin's World War

II-era Boston Red Sox.

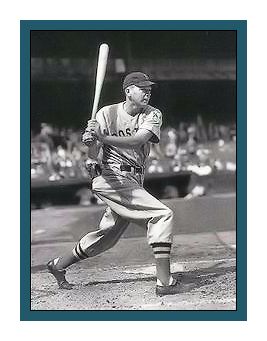

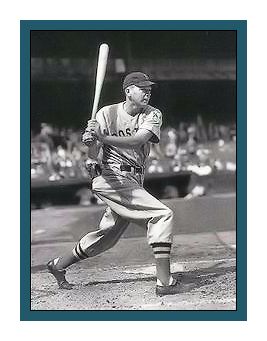

A scrappy, curly-haired Alabaman who spoke with a Southern drawl, Finney

stood 6 feet tall and weighed 180 pounds; batted from the left side; and

threw from the right. He spent 15 years in the major leagues between 1931

and 1947, and fanned just 186 times in 4,631 at-bats, or only once for

every 24.9 official turns, one of the 50 best ratios in major-league

history. A .287 career hitter who hustled whenever he was on the field,

the fiery Finney slugged just 31 big-league home runs, but hit 203 doubles

and 85 triples.

At his best in his natural position, right field, Finney also played first base

for Mack and Cronin. Most often a reserve, Finney still appeared in 100 or more

big-league games in seven seasons. He was highly competitive and loved to needle

opponents.

A fine

all-around athlete "who never has any winter weight to melt," Finney continued

his career as a passionate player-manager in the minors when his major-league

career ended. Later, he returned home to Alabama to run a small business with

his older brother, Hal, a former National League catcher.

Louis Klopsche Finney was born on August 13, 1910. Lou left high school to

follow his brothers to Birmingham Southern, but quit after he fractured both

legs in a football game. He returned home and earned his diploma from Five

Points High, where he starred as a third baseman for the baseball team and

lettered in football and basketball.

Finney played semipro baseball at Akron, Ohio, in 1929, but when the 1930 Census

reached the Five Points Hamburg Region of Chambers County in April, “Lewis” was

back on the family farm and at work at a rubber plant. Legend suggests that he

was seated behind two mules in late June 1930, when a neighbor informed him that

the Carrollton (Georgia) Champs of the Class D Georgia-Alabama League needed an

outfielder. Finney answered the call. Just 19 years old, he launched a barrage

on the league in his first season in organized baseball. He batted .389 with 17

doubles and 7 home runs before Carrollton and Talladega, the league's cellar

dwellers, disbanded on August 14.

By that time, he had been spotted by Ira Thomas, a scout for Connie Mack’s

Athletics. Philadelphia purchased Finney's contract after the 1930 season and

assigned him to the Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Senators of the Class B New

York-Pennsylvania League for 1931. However, he failed to impress the Harrisburg

manager and was transferred to the York (Pennsylvania) White Roses in the same

league. At York, he resumed his assault on minor-league pitchers. He batted .347

for manager Jack Bentley and earned

The Sporting News’ All-NYP

honors.

Mack purchased the young Alabaman's contract for the season's final weeks. Just

a month past his 21st birthday, Finney made his big-league debut for

the Tall Tactician on September 12, 1931, against the St. Louis Browns. The

Athletics were in the midst of a 19-game home stand, and Finney appeared in nine

games and rapped out nine hits, including a triple, in 24 at-bats. He scored

seven runs and drove in three in his three-week stint.

Finney spent the 1932 season with the Portland Beavers of the highly competitive

Pacific Coast League. Often called the Third Major League, the PCL boasted a

number of future and former major leaguers. Two of the best in 1932 were Finney

and fellow Philadelphia farmhand Michael Franklin "Pinky" Higgins, both of whom

made The

Sporting News’ All-PCL team. One or the other was among the league

leaders in every offensive category to propel Portland to the PCL pennant with a

111-78 record. Finney finished third in the league's Most Valuable Player

voting.

Still 22 years old, Finney rejoined the Athletics and his Portland teammate

Higgins, who was Philadelphia's third baseman in 1933. Finney enjoyed a splendid

spring training and was viewed as a replacement for Al Simmons, one of

baseball's all-time great outfielders, whom Mack had traded to Chicago before

the season. When the regular season started, Finney was hot. But he was nervous

and quickly cooled off, and Mack sold his contract with the right to recall the

outfielder on 24 hours’ notice, to Montreal of the Double A International

League. There, Finney hit .298 with 23 extra-base hits in 65 games. His second

home run for the Royals came on his last at-bat, on August 15, after Mack

notified Montreal to return Finney to Philly. The sudden recall derailed the

Royals’ playoff hopes and created friction between Montreal and Mack. Back in

Philadelphia, Finney continued to hit well.

Between

seasons, there were rumors that Mack would trade the youngster to Boston, but

when the 1934 season opened; he was Philadelphia's fourth outfielder behind

Indian Bob Johnson, Doc Cramer, and Ed Coleman, and sometimes spelled slugger

Jimmie Foxx at first base, roles he reprised the next year. Finney played in 201

games in 1934 and 1935, batted .276, and though he hit just one homer in the two

seasons, he smacked 22 doubles.

The

Alabaman was a valuable stopgap for Mack in those two seasons. When Higgins was

hurt in 1934, Foxx moved to third and Finney held down first, and when rookie

Wally Moses crashed into a fence and was injured in 1935, Finney moved back to

the outfield. In 1935, Mack sent Foxx behind the plate 26 times and played

Finney at first, but a spate of Athletics injuries nixed the experiment.

Mack

continued to feel the effects of the Depression and declining attendance at

Shibe Park, and dealt the powerful Foxx to Boston before the 1936 season for

players and cash. Rookie Alfred “Chubby” Dean (77 games) shared the first-base

duties with Finney, who also played the outfield in 73 games. Despite Finney’s

fine season, he and Dean split the first base duties in 1937. (Dean, a lifetime

.274 hitter, later unwisely moved to the mound and compiled a 30-46 record and a

5.08 ERA as pitcher.) Finney did play 50 games at first in 1937, made the only

appearance of his career at second base, where he recorded an assist, and played

39 games in the outfield. Bouncing around the lineup and battling an ailment he

picked up in Mexico in spring training, a hernia, a chronic sinus infection, and

later, appendicitis, he saw his average slip to .251. He hit another

round-tripper, again inside the park, his sixth home run in six major-league

seasons. With 10 days left in the regular season, Finney, with Mack's consent,

returned home to Alabama and underwent surgery on his sinuses, had a hernia

repaired, had the inflamed appendix that had bothered him for months extracted,

and had his tonsils removed.

Healthy in 1938, the 27-year-old “Alabama Assassin” enjoyed a power surge when

he slugged 10 home runs – with nine of them clearing the fences. In 1939 Siebert

started at first base and Finney batted just .136 in nine games before Mack sold

him to Boston on May 9. The Alabaman enjoyed great success as a pinch-hitter –

he led the AL with 13 pinch hits in 40 at-bats -- then finished the season at

first base after Foxx underwent an appendectomy.

For the Red Sox, Finney flourished under manager Joe Cronin and veteran scout

and hitting instructor Hugh Duffy. He credited Duffy, the legendary New

Englander, for teaching him to snap his wrist. The results were

immediate. Finney batted .325 in 249 at-bats in his 95 games with Boston, with

22 extra-base hits, including a pinch-hit home run at Sportsman’s Park. The next

spring, he praised Duffy to the

Boston

Traveler’s John Drohan, among others: “I was with the Red Sox for a

week or so when Hughie Duffy, who led the National League in batting way back in

1894, asked me if I were willing to take some advice from a 76-year-old man

(Duffy was actually 72 at the time). As I realized I was not going anywhere, I

told him I was more than willing. Consequently, Hughie, who was one of the Red

Sox coaches and batted grounders in the infield practice despite his age,

converted me from a choke hitter into a batsman who grabbed his bat way down at

the end and swung from the hip. He also changed my stance in the batter’s box,

spreading my feet a trifle further apart. He also told me to put more wrist into

my swing like Ted Williams. Well, I was not hitting my weight when I left the

Athletics and I wound up the 1939 season with a mark of .310, the best I ever

had.” The Red Sox posted an 89-62 record and finished second to the Joe

DiMaggio-led Yankees, who methodically captured their fourth straight AL pennant

despite the loss of Lou Gehrig to the illness that would tragically cut short

his life.

In spite of a broken finger in spring training, courtesy of Cincinnati's Johnny

Vander Meer, and a nagging cold, Finney enjoyed another fine season in Boston in

1940. He played in the outfield in place of the injured Dom DiMaggio, and hit so

well that the Red Sox postponed DiMaggio’s return, before Finney himself

suffered a leg injury. When he came back, he moved to first when Foxx injured

his knee in a collision. When Double-X returned, Cronin asked his team captain

to play catcher for the injured Gene Desautels, which allowed the Boston manager

to keep both Finney and DiMaggio in the lineup. In either position, Finney hit

well. He was the first major-league player to record 100 hits that season,

ranked among the league batting leaders through the summer, and finished with a

.320 average, ninth best in the AL. Finney and New York's Charlie "King Kong"

Keller tied for second in the league with 15 triples, four behind league leader

Barney McCosky of Detroit. The 15 triples were a career best for Finney, who

also achieved personal highs with 31 doubles and 73 runs batted in. He scored 73

times and was the AL’s toughest man to strike out, fanning just once per 41.1

at-bats, well ahead of runner-up Charlie Gehringer of Detroit, who struck out

once every 30.2 AB’s

In July,

Finney made his only All-Star Game appearance, and coaxed a walk from Carl

Hubbell in the NL's 4-0 win. On May 11, he hit one of his two career grand

slams, off Marius Russo at Yankee Stadium, to help Boston send New York to a

defeat, the Bronx Bombers’ eighth straight. Though never again an All-Star, he

continued to provide valuable depth for the Red Sox the next two years. In 1941,

Finney banged out 24 more doubles and 4 home runs, and batted .288. In 1942, he

hit .285 in 113 games for the Red Sox at the age of 31. He was particularly

adept in night games, collecting 14 hits in 35 after-dark at-bats between 1939

and 1941 -- a .400 average, even better than the .324 mark Williams posted in 34

at-bats.

By 1942, World War II was changing the face of baseball. Players began to leave

the game to enter the military or to work in industries vital to the war. After

the season, Williams entered the Navy, where he served as a fighter

pilot. Finney, who had applied for a chief specialist rating in the Navy at one

point, returned home to the 171-acre cotton farm near White Plains, Alabama,

that he and his wife, the former Margie Griffin, owned in Chambers

County. Finney, who was 32 years old and had no children, had received his draft

notice, and had to choose between entering military service and staying on his

farm to grow food, an occupation deemed critical to the war effort. On January

11, 1943, the

New York

World

Telegram reported, “Lou Finney, Red Sox outfielder, was told by his

Alabama draft board to remain on his farm or be inducted.” He voluntarily

retired from the game and sat out the entire 1943 season and the first months of

the 1944 campaign. In June, two weeks after the Allies invaded France on D-Day,

Finney left Alabama and returned to baseball and Boston, though

The

Sporting

News noted he weighed a hefty 225 pounds when he reported. After a

week of conditioning, Finney was activated on June 25, and batted a respectable

.287 in 68 games. At the end of the season, his teammates voted him a full

share, $241.87, of their fourth-place money.

However, his Alabama draft board tracked Finney to Boston in August, and

delivered notice that he had been called to active duty and was required to

report for a medical examination. Again Finney returned to his farm. While

Finney farmed through the first half of the 1945 season, the Allied nations

subdued Germany in May, and moved closer to victory in the Pacific over

Japan. Once again, Finney journeyed north to rejoin the Red Sox.

Cronin,

who broke a leg on April 19 and hadn’t played since, inactivated himself to open

a roster spot for Finney on July 15, but used the Alabaman just twice, both

times as a pinch hitter, before the Red Sox sold his contract to the defending

American League champion St. Louis Browns on July 27, 1945.

At 35, he returned to the Browns at the start of the 1946 season. But the war

had ended the previous year, and many of the veterans had started to return to

organized baseball. And though Finney collected nine singles in 30 at-bats, a

.300 average, the Browns released him on May 29.

That summer, Finney returned to his roots and played 45 games at first base and

in the outfield for the last place Opelika Owls and later the second-place

Valley Rebels, who represented the tri-city area of Valley and Lanett, Alabama,

and West Point, Georgia, in the Georgia-Alabama League. He batted .299 and

clubbed six home runs for the two teams.

Finney took one more shot at the brass ring when he pinch-hit unsuccessfully

four times for the Philadelphia Phillies, his only at-bats in the National

League, before the Phillies released him on May 13, 1947, at the age of 36.

Less than a week later, with his major-league career done, Finney returned to

the minors, this time with St. Petersburg in the Class C Florida International

League. With the Saints floundering in last place and 17 games behind in the

standings, his old teammate Jimmie Foxx was fired on May 17. Finney took over a

few days later as a player-manager and guided St. Pete to a 71-80 record, good

for fifth in the eight-team league.

Lou ran

the family firm for the remainder of his life with Hal. Like Lou, Hal broke into

the major leagues in 1931. That year he played 10 games; six at catcher and four

as a pinch-hitter, for the Pirates. He played 31 games the next year, and 56 in

1933, when he hit his lone homer and drove in 18 runs. He played in five games

in 1934, spent the rest of that season in the minors with the Albany (New York)

Senators in the International League, missed the 1935 season because of a

fractured skull and an eye injury suffered in a tractor accident and started the

1936 season without a hit in 35 at-bats before the Pirates released him. The

brothers worked together in Chambers County until April 22, 1966, when Lou, at

the age of 55, suffered a coronary thrombosis, a blockage of a coronary artery,

and died at the Chambers County Hospital in La Fayette.

|