|

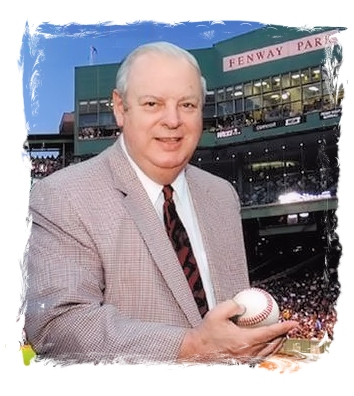

Lou Gorman was once described as “chubby, kinetic, rather trim … and affable and reasonable,” and one of the most common words used to depict him was “optimist.” He turned these qualities into a relatively successful tenure with the Red Sox. Unfortunately for Gorman, his GM job occurred in an organization with muddled and overlapping lines of authority, and he never proved particularly adept at managing through and around the hierarchy. James Gerald Gorman was born on February 18, 1929, in Providence, Rhode Island. He worked stocking shelves in a grocery store to help support the family. Mostly though, as a youth he loved sports. By the time he was in high school at LaSalle Academy, he had become one of the region’s top athletes in football, basketball, and baseball. One of his prep highlights was playing quarterback for LaSalle in a game in the Sugar Bowl in New Orleans against Holy Cross Prep School. As a first baseman on the baseball team, Gorman earned the enduring nickname Lou because his play reminded some of Lou Gehrig. After high school Gorman gave professional baseball a try, playing one season in 1948 with his hometown Providence Grays in the Class-B New England League. Unfortunately, Gorman struggled at the plate, which quickly ended his professional career. Instead, Gorman accepted a basketball scholarship to Stonehill College in Easton, Massachusetts, where he was also captain of the baseball team. After graduation in 1953 Gorman joined the Navy. When Gorman left the Navy eight years later, he decided he wanted a job in baseball. He took a two-week course at the Mitchell Mick Baseball School, learning to run a minor-league baseball operation, and headed off for the December 1961 winter meetings. Toward the end of the meetings, a chance introduction in the hotel bar landed him the general manager’s job for the Lakeland Giants, San Francisco’s Class-D affiliate in 1962. The next year Gorman advanced up the minor-league chain, accepting a position as the GM for Kinston in the Class-B Carolina League in the Pirates system. Gorman was slowly making a name for himself, and the Orioles farm hired him to be the assistant farm director in 1964. On its way to becoming baseball’s model organization, Baltimore was a perfect spot to learn the business of building a major-league team. At the time the team was instituting the “Oriole Way,” a blueprint to systematize scouting, training, and conduct throughout the organization. A couple of years later Lou became farm director. In this role he oversaw a number of well-respected future pennant-winning big-league managers in their minor-league apprenticeships. The four-team expansion for the 1969 season offered Lou an opportunity for a new opportunity and a significant pay raise. Kansas City brought Gorman in as director of minor league operations. He helped put together the Kansas City Royals Instructional Manual to highlight how each defensive play should be executed. With his background in the highly successful Oriole Way, Lou advocated consistent instruction throughout the Royals organization. Owner Ewing Kauffman also had him oversee his pet project, the Kansas City Baseball Academy. By 1973, however, while the Academy had produced several prospects, it had become too costly for its limited return and Kauffman reluctantly shut it down. For the next several years Gorman remained an important senior executive in the Royals front office. When the Seattle Mariners came calling in April 1976, offering him the opportunity to build his own team, he jumped at the chance. Seattle had just been awarded an expansion franchise. Building a major-league organization from scratch is a huge undertaking and Lou had thorough experience with the Royals in 1969 and had a good sense of the challenges he faced. But because of his owner’s lack of capital, he had to both build for the future and also make sure the team played well enough to keep the fan base captivated. True to his outline, Lou hired a solid, relatively large scouting staff. He continued to try to build an organization and stock it with capable players during the off-season. By early in the 1978 season, however, it became clear that all decisions were really being governed by their effect on the franchise’s constricted finances. In January 1979 Seattle changed top executives, further limiting Gorman’s scope of authority. He was now GM in little more than name only. When the New York Mets, called Lou to gauge his interest in becoming his key baseball lieutenant as VP of baseball operations, he happily accepted the opportunity. He relished the challenge of turning around the Mets and believed he had been assured of the Mets GM job in the future. However, he was highly intrigued when his childhood favorite, the Boston Red Sox, approached him in December 1983. After some soul-searching, he accepted the position of VP of baseball operations with the understanding that current GM and part-owner Haywood Sullivan would move up to an executive role within a year, naming him the GM. And in fact that is what happened. In June 1984, as part of an overall conclusion to a long-running takeover battle for control of the team, Sullivan was promoted to CEO and Gorman to GM. The team Lou inherited had just finished 78-84 but had a number of positives heading into 1984. They had a good pitching staff led by young pitchers, and about to welcome Roger Clemens, one of the American League’s best players in When manager Ralph Houk retired after the 1984 season, he named John McNamara to replace him. After falling back to .500 in 1985, he became more aggressive. More significantly, in August 1986 during the pennant chase, Gorman made one his best trades, surrendering little and landing two key contributors, shortstop Spike Owen and outfielder Dave Henderson. In 1986, led by strong seasons from one of the decade’s best pitching seasons from Clemens, the Red Sox won the pennant, but lost to the Mets in the World Series. Not surprisingly, given that he was coming off a championship season and because of his seeming reluctance to make significant moves, he left his team pretty much intact for 1987. Haywood Sullivan had never really adjusted to player free agency and was generally loath to pay new-found market values. Sullivan’s attitude left Lou hamstrung in the pursuit of the best available free agents. Furthermore, Sullivan remained an active participant in the front office’s internal deliberations at the winter meetings every year, further constraining Lou's scope of action. Lou was also hampered in that he had extremely small baseball operations staff. The Red Sox ownership examined closely involved in contract negotiations with the players. As opposed to some franchises in which the GM is given a target budget and allowed to build a team, Sullivan and Harrington wanted review all significant contract proposals in advance. This became particularly exasperating when Clemens held out for a salary increase after the 1986 season. Lou took much of the heat for the dispute, and in the end Sullivan formally took over the negotiations for the Red Sox. He also began to experience the intensity and volatility of the Boston press, which the folksy Gorman never really adjusted to. The team fell back in 1987, and at the All-Star break in 1988, Jean Yawkey expressed her dissatisfaction over the performance of the team, telling Lou to replace John McNamara. With Yawkey’s approval, Gorman named coach Joe Morgan the new manager, technically on an interim basis. Under Morgan the club rebounded to capture the AL East Division title before falling to the Oakland A’s in the ALCS. The team remained competitive over the next three years, including one more division title in 1990. Lou smartly rode his nucleus while making a several lesser moves that benefited the team. But once again ownership decided to change managers. In 1991 the team had been within a half-game of first in late September, but finished 3-11 down the stretch, and there had developed “the perception that the club had gotten away from Morgan and that there was dissention on the ball-club. Once again Gorman was not part of or in this instance even aware of the decision to replace the manager. While he knew of their general discontent, he was as surprised as Joe Morgan when at a meeting with him and Morgan, the owners told the manager he was out. By 1992 many of the naturally occurring holes due to injuries and retirements were filled by journeymen. There was loosening of the purse strings by ownership. Clemens was re-signed for a record contract, Gorman spent liberally to land hurlers Frank Viola, Danny Darwin, and Matt Young. But The team also struggled to retain its stars in free agency. Hurst had left after the 1988 season, and the Sox lost both Boggs and Burks after the 1992 season. In 1993 the team again finished below .500 and John Harrington sacked Lou. Harrington kept Gorman with the Red Sox in an honorary role, one he retained for many years, even after the team was sold to a consortium led by John Henry. Well respected for his generosity and integrity, he remained an ambassador for the organization. Lou Gorman died, on April 1 2011 at 82 of congestive heart failure. |

|||||