|

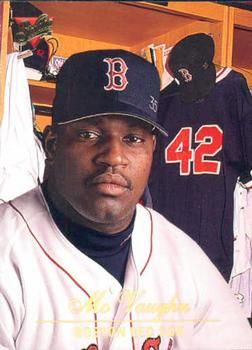

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||||

Maurice (Mo) Vaughn, the 6'1" 240 lb. first baseman for the Boston Red Sox, was named the American League's Most Valuable Player in 1995. Born on December 15, 1967 in Norwalk, Connecticut, Vaughn's hometown is Easton, Massachusetts. He is the son of Leroy Vaughn, a former high school principal and football coach, and Shirley Vaughn, an elementary school teacher. Mo's mother taught him to play baseball when he was only three-years-old. As his mother did, Mo hits left, while throwing right. Mo attributes his competitive nature to his mother, though both of his parents encouraged acceptable schoolwork in exchange for his playing sports. Mo learned charitable ways as a child and his entire family gave gifts to the homeless at Christmas time. This may account in part for Mo's highly charitable nature today. For, in addition to newspaper and magazine clippings detailing Mo's on-field victories, his press file is filled with an equal number of stories detailing his charitable off-field accomplishments. Vaughn received the nickname "Mo" from a high school athletic director when he was in the ninth grade. The director couldn't say Maurice fast enough, so he shortened it to Mo. Vaughn's very first baseball game was played when he was nine-years-old in Norwalk, Connecticut and he played third base. By age 12, Mo had accumulated around 30 homeruns in a 13-game season and by age 16 he was hitting balls out of the park in his first Senior Babe Ruth League game. Mo attributes his current success to the fact that he always played baseball with older kids and practiced daily. As a child, however, football was Mo's favorite sport. Vaughn attended the rural New York preparatory school Trinity-Pawling during high school and spent another three years at Seton Hall College where he broke the career record of home runs by a Seton Hall player when he was a freshman, with 28 long balls. During his three-year career with Seton Hall's Pirates, Mo held a .417 batting average, hit 57 home runs, drove in 218 RBIs and was named to the All-America team each season. Acquired by the Boston Red Sox during the first draft round in 1989, Mo spent 1990 in Pawtucket, Boston's top farm club, where he hit .295, 22 home runs and 78 RBIs in only 108 games. In 1991, after 14 home runs and 50 RBIs at Pawtucket, Mo made his major league debut on June 27, 1991 in the majors, where he batted .260 with four homers and 32 RBIS. The 23-year-old Vaughn, having never played a day of major league baseball before 1991, had fans eager for him to perform. However, unaffected by the crowd's praise, Vaughn told a Sports Illustrated reporter that "... the Boston Red Sox will be good whether I make the team or not. The attention doesn't bother me. You only play this game for ten years. To be a good man, a good person, that's what people remember." Mo's sophomore season with the Red Sox in 1992, however, proved to be a difficult beginning, with his averaging .185 for the first 23 games and dropping to two homeruns. During the season at Fenway Park, Vaughn struggled between Boston and minor league affiliation with Pawtucket, ending the season with a dismal .234 batting average and only 13 homers. During this time, Mo did a short stint at Pawtucket, returning to the lineup in June. Vaughn felt extremely bad about this and said to a Sports Illustrated reporter, "It was like I was a bad person or something. I had to make sure that wasn't the case. See, in Boston they want success right away. You can't afford to have any problems." Hence, Vaughn did something about it. Angry and confused, he was saved by the gifted hitting coach Mike Easler, who knew how to handle Vaughn. Easler helped Vaughn work on his stance, swing, preparation, and confidence. Under the tutelage of Easler, known in his playing days as the "Hit Man," Vaughn made a formidable comeback. Vaughn states that Easler saved his career. Upon Vaughn's return to Boston after his six weeks at Pawtucket, he came back hitting the ball harder than anyone in baseball. Vaughn (who wears number 42 in honor of Jackie Robinson) was a terrific success from 1993's Opening Day onward, thanks in no small part to Easler. Mo was hitting .331, the fifth best in the American League, and leading Boston with seven homers and 31 RBIs. On May 23, 1993 the 25-year-old Vaughn hit two homers against the Yankees from veteran pitcher Jimmy Key, known to have given only five homers to left-handed batters during the decade. The Boston Red Sox, in fifth place by June 21, 1993, made an impossible comeback, similar to the 1967 season which began slowly and ended with the American League pennant. By August, they were in a three-way tie for first place with the New York Yankees and the Toronto Blue Jays, having won their tenth straight game in a row, winning 25 out of the last 30 games. The 10th straight Red Sox victory was 8-1 against the Oakland A's, a team that once regularly beat them, featuring a grand slam by "Hit Dog" Vaughn. By this time, Vaughn had chalked up 14 homeruns, with an average of .324 and nearly double his RBIs from the start of the season at 64, wielding his 36-inch, 36-oz. black bat. While the Boston Red Sox had not won a world championship since Babe Ruth was traded away, everyone in Boston was excited about the team. In spite of a baseball strike in 1994 it was Vaughn's best season yet. Mo batted a .297 average, with 29 homers and 101 RBIs, being named the Most Valuable Player by the Boston Writers Association. Vaughn led the Sox in nearly every batting category. The then 26-year-old slugger was the brightest star for the Red Sox, helping them to become contenders in the American League. Vaughn exhibited poise, dedication, hard work and devotion to his community. In March of 1994 Vaughn hit a home run in Anaheim, California for 11-year-old Jason Leader, a Boston cancer patient. At that time Mo told Forbes reporter, ".... all I was doing was a little bit for a young man. I hope it gave him just a little more strength to push on, to keep going." Vaughn feels that this is where the real heroism lies, not in a breathtaking homerun. In 1995 Vaughn played a large part in the Sox's winning the Eastern Division Championship, as did the newly acquired Jose Canseco even though it was reported in October of 1995 that Mo and Canseco had let their teammates down in the first two games of the playoffs against the Cleveland Indians. The Red Sox lost both times, including a 4-0 loss, leaving them one game from elimination in the best-of-five series. Both Vaughn and Canseco went hitless in 10 at- bats. Vaughn, a major playing force during the 1995 season, did not meet with success early in the play-offs. As it turned out, Vaughn won the American League's Most Valuable Player award in the winter of 1995 as a result of his .300 batting average, 39 home runs, 126 RBIs, 11 stolen bases, team leadership, and community service. Vaughn won the award in one of the closest, most controversial votes in history, edging out Cleveland Indians left fielder Albert Belle. Although Belle was known to be uncooperative and surly with the fans and media, Vaughn certainly had the numbers to support his win, including the numerous home runs hit in Fenway Park, especially unfavorable to left-handed hitters like Vaughn. Vaughn continued to play the game with the enthusiasm of a Little Leaguer. During the 1995 season the Red Sox soared because of Vaughn. Coming off of three straight losing seasons, the team was expected to finish fourth in their division, particularly since pitcher Roger Clemens (an MVP winner) was out for 31 games at the start of the season with tendinitis and Jose Canseco (another MVP winner) was out for 32 games in the early season with groin strain. Third baseman Tim Naehring felt that Vaughn possessed more than great athletic skills and attributed the MVP award to Vaughn's presence, confidence and positive attitude. Canseco felt that Vaughn carried the team during the 1995 season and shortstop teammate John Valentin felt that Vaughn meant everything to the team who had won the American League Championship. Not only was Vaughn a powerful hitter, but a big moneymaker as well, earning $2.7 million in 1995. During this time Vaughn also actively supported the Food Bank, the Jimmy Fund, and the Boys and Girls Club in addition to his Mo Vaughn Youth Development Program. At a news conference held at Vaughn's community center for youth in Boston after he received the award, Vaughn credited the kids with helping him to win the award as much as anything. Vaughn was further honored that year by being selected to play in his first All-Star Game and he was named the American League's Player of the Week. Vaughn also received the 1995 Bart Giamatti Award by B.A.T. (Baseball Assistance Team) for his community service. Vaughn, considered one of the nicest players in baseball, was actively involved in the Boston community. The project closest to Vaughn's heart is the Mo Vaughn Youth Development Program in Dorchester, which he co-founded in 1994 with two of his childhood friends, Bryan Wilson and Roosevelt Smith. In November of 1995 Vaughn's appearance at a Cape Cod auction helped to generate $15,000 for "Dream Day" which sponsors outings for children with cancer and other life threatening diseases. While speaking with young students, Mo steers them into action and away from blaming their lack of achievement on circumstances. The success of Mo's program is spoken through the attending students, who credit Mo for helping them to stay in school, get better grades and think more positively. Vaughn has said that he feels successful if he can impact four or five kids out of 300, with more than that being a bonus. Vaughn immediately establishes rapport with students, wearing baggy sweats and sporting earrings, a tatoo, and a backwards hat. Vaughn's message to youth centers on staying away from drugs, believing in oneself and staying in school. Vaughn has been on a mission to use his love of baseball to reach kids and it works. Vaughn was Grand Marshal of Boston's Christmas parade in 1994 and he arranged for 250 Boys and Girls Club children to a attend a performance of the "Nutcracker Suite." As quoted in Forbes, Mo "... want{s} to be remembered as a person who played hard every day, and cared about winning, and helped the kids and people who are not as fortunate ...." While having been described as the Red Sox's most lovable player, loved by fans, both young and old, Mo is far from self-righteous, tending to be rowdy on road trips and in the locker room, where he dances to rap music. One of the best hitters in the major leagues, Vaughn averaged .301 at plate, 31 homers, and 103 RBIs for the 1994-96 seasons. Vaughn has been compared to Barry Larkin, shortstop for Cincinnati Reds, both of whom showed potential at an early age, came from big households with strong parents, and grew up learning right from wrong. Vaughn, who walked the straight and narrow while growing up, learned in college the combination of hard work, sacrifice and discipline which paid off. While Vaughn was easily the most popular Red Sox player of his time in 1995, he became an even better hitter after 1995, tightening up his swing, moving closer to the plate, and able to hit any pitched ball. The All-Star Vaughn was referred to as the heart and soul of the team by manager Kevin Kennedy. In the early season of 1996 Mo injured his finger, but continued to play, being named the American League's Player of the month in May of 1996 and player of the week for the week of September 8-14, again becoming a top contender for the MVP award. In March of 1996, Vaughn agreed to a three-year $18.6 million contract with the Red Sox, making him the highest paid player in the team's history, with an average annual salary of $6.2 million. Vaughn said that signing the deal was perhaps the highlight of his life. However, things took a dip for the Red Sox in early 1997 with the loss of veteran players Jose Canseco, Roger Clemens and Mike Greenwell. Vaughn decided not to worry about where the team was going though, focusing on his job as a ballplayer. Vaughn hoped to grow professionally by becoming more patient, increasing his walk total and decreasing his strikeouts. Vaughn remains committed to going out there and giving it his best, regardless of uneasiness concerning the team's performance. During the early 1997 season Vaughn was on the disabled list because of arthroscopic surgery on his left knee to replace torn cartilage, but after the All-Star Break, Vaughn returned to play, hitting a home run his first game back. A great baseball star and conscientious champion for America's youth, Mo Vaughn continued to prove that he is still the "Hit Dog" both on and off the field. Though Vaughn's powerful personality and extensive charity work made him a popular figure in Boston, he had many issues with the Red Sox management and local media; his disagreements with Boston Globe sports columnist Will McDonough and Red Sox general manager Dan Duquette were particularly acute. As an outspoken clubhouse leader, Vaughn repeatedly stated that the conservative Sox administration did not want him around. Incidents in which he allegedly punched a man in the mouth outside of a nightclub and crashed his truck while returning home from a strip club in Providence led to further rifts with the administration. Vaughn hit a walk-off grand slam in the ninth inning of Opening Day at Fenway Park against the Seattle Mariners in 1998. Despite this auspicious start, the season was filled with acrimony, as Vaughn and the Sox administration sniped at each other throughout the year. Vaughn formed a formidable middle of the lineup with shortstop Nomar Garciaparra. The two combined for 75 home runs in 1998, Vaughn's final year with the club. After the Cleveland Indians knocked Boston out of the playoffs in the first round, Vaughn became a free agent. Almost immediately, he signed a six-year, $80-million deal with the Anaheim Angels. It was revealed on December 13, 2007 in the report by Senator George J. Mitchell that Vaughn had purchased steroids or other performance-enhancing drugs from Kirk Radomski, who said he delivered the drugs to him personally. Radomski produced three checks, one for $2,200 and two more for $3,200, from Vaughn, one of the latter dated June 1, 2001, and another dated June 19, 2001. Radomski said that the higher checks were for two kits of HGH, while the lower one was for one and a half kits. Vaughn's name, address and telephone number were listed in an address book seized from Radomski's house by federal agents. Vaughn's trainer instructed him to take HGH in attempt to recover from injury. Mitchell requested a meeting with Vaughn in order to provide Vaughn with the information about these allegations and to give him an opportunity to respond, but Vaughn never agreed to set a meeting.

|

|||||