|

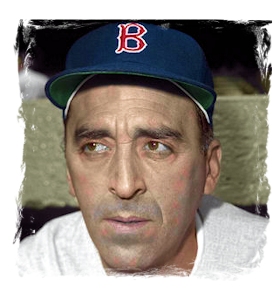

Sal Maglie was born on April 26, 1917, in Niagara Falls, NY. Salís passion for baseball mystified and angered his parents, and as a child he had to sneak out of the house in order to play. In his early years he was such a poor pitcher that his sandlot teams rarely let him take the mound. Since his high school did not have a baseball team, he went out for basketball, becoming one of the teamís stars. Nearby Niagara University offered him a basketball scholarship, but he turned it down, maintaining a stubborn allegiance to baseball, and to pitching in particular. He held a job at Union Carbide, one of Niagara Fallsí many chemical plants, and pitched for the company team, as well for local semipro teams. Sal also joined the Niagara Cataracts, a local team that lasted less than one season. He then spent almost three seasons with the Double-A Bisons, each worse than the previous one. In 1940 he was placed with the Jamestown Falcons of the Class D Pony League. In 1941 he moved up to the Elmira Pioneers of the Class A Eastern League, and there Sal finally hit his stride, winning 20 games and achieving an excellent 2.67 ERA. In 1942, shortly after the beginning of World War II, Sal failed his pre-induction physical due to a chronic sinus condition. With the manpower shortage in baseball, his mediocre record was sufficient for the New York Giants to snap him up for their Jersey City farm team. But he resigned after the 1942 season and returned to Niagara Falls, where he spent the next two years working in a defense plant. In the spring of 1945, Sal returned to the Jersey City Giants, where he compiled another losing record, but with the continuing manpower shortage, in August he was called up to the majors. Although in his two months with the New York Giants, in 1945, the 28-year-old rookie compiled a modest 5-4 record, he tossed three shutouts. At the end of the 1945 season Sal went to Cuba, and there he began a tough, demanding apprenticeship that would transform him from a marginal wartime hurler into one of the top pitchers of his time. He left organized baseball in the United States and played for two seasons in 1946 and 1947, in the Mexican League. From there. Sal emerged as a grim, tough, ruthless competitor unfazed by weather, taunts, or pressure, a pitcher who could bend a curve like a pretzel, or send a batter sprawling with a fastball that grazed his chin. After 1947 he did not return to the crumbling Mexican League, but joined a barnstorming squad, consisting of other Mexican League refugees, and the group traveled around by bus, taking on local semipro teams. The team failed to bring in enough money to cover expenses, and disbanded in August of 1948. Back in Niagara Falls, he used money saved from his years in Mexico, to purchase a home and a gas station, and tried to resign himself to life as a gas jockey. But he was miserable and when he was invited to pitch in the Provincial League in Quebec, he put in an outstanding season in Canada in 1949, leading the Drummondville Cubs to a championship. Sal began his 1950 season with the Giants in the bullpen, working only sporadically, and in daily dread of being sent back to the minors or released. He finally pitched the contest that turned his career around in July. He threw an 11-inning complete game, defeating the Cardinals. Sal pitched brilliantly that year, finishing with an 18-4 record, at one point hurling four straight shutouts and 45 consecutive scoreless innings. In 1951, he enjoyed his most successful year, contributing 23 wins to the Giantsí pennant drive. Although Sal enjoyed another successful season, going 18-8 in 1952, he began experiencing back trouble that limited his effectiveness. In 1953 his back problems intensified, and at 36, many assumed heíd reached the end of the line. But he bounced back for another successful season in 1954, while the Giants won the world championship. In July 1955, the Giants sold Sal to the Cleveland Indians. There, he mostly warmed the bench, and even considered retirement. Early in the 1956 season, the Indians sold him to his erstwhile archenemies, the Brooklyn Dodgers. Dodger fans, at first were horrified to see their teamís nemesis in Dodger blue, but soon warmed to Sal as the aging hurler won key games that enabled the Dodgers to gain their final Brooklyn pennant. During a listless 1957 season, as the aging Dodger squad played out its final Brooklyn season before their move to Los Angeles, Sal was sent to the Yankees, the last player to wear the uniform of all three New York teams. The Yankees then passed him on to the St. Louis Cardinals, where he stumbled in his final major league season. When spring training ended in 1959, the Cards handed Sal his unconditional release. In an effort to give him ten years in the majors and make him eligible for a pension however, the Cards came up with a combination of minor league coaching and scouting position for 1959. But Sal disliked the job and did not renew his contact for the next year. Then Sal opened a new chapter in his baseball life, in October 1960, when he accepted the post of pitching coach for the Boston Red Sox. The Red Sox teams of the early 1960s were poor-playing squads, and Salís efforts to mold a winning pitching staff mostly went to waste. But in 1961 Bill Monbouquette set a team record with 17 strikeouts in a single game, and gave much of the credit for his achievement to Sal. In 1962, in an achievement almost unheard of for a second division squad, Monbouquette and Earl Wilson tossed no-hitters and both credited Sal for the marked improvement in their pitching performances. In addition, Dick Radatz emerged as the teamís ace reliever and Sal taught him how to use the lower part of his body, using his legs to drive off the mound, and getting more velocity on the fastball. It probably put four or five miles an hour more on his fastball and what he learned from Sal, helped him for the rest of his career. But coaching success is no guarantee of continued employment, as Sal learned at the end of the 1962 season, when he fell victim to managerial changes. The new manager, Johnny Pesky, wanted to name his own coaching staff, and Sal was let go. For the next three years, Sal remained at home, supporting himself and his family through speaking engagements, the businesses in which he had invested in Niagara Falls, and his small pension. Although the Sox invited him to rejoin the coaching staff in 1965, he couldnít, because heíd accepted a post with the New York State Athletic Commission. But the following year, with Bostonís offer still open, the lure of baseball proved too strong, and he returned to the Red Sox for the 1966 season. The Red Sox season of ďThe Impossible DreamĒ proved to be a nightmare for Sal. He had lost his wife in February and from the start, he did not get along with Dick Williams, who had wanted to hire his own pitching coach, but couldnít, because Sal had signed a two-year contract. As one of the most exciting seasons in Red Sox history unfolded, Salís unhappiness deepened, as he felt slighted and ignored by Williams. The one bright spot for him was the emergence of Jim Lonborg as the ace of the staff who also credited much of his success to Salís coaching. Despite whatever contribution Sal made in 1967, the day after the Series ended, Dick Williams fired him. Sal benefited from league expansion in the late í60s. In 1968 he was hired as a scout and pitching coach for the Seattle Pilots, set to begin play in 1969. He spent 1968 coaching for their affiliated Newark (N.Y.) Co-Pilots, and when the Seattle franchise began play in 1969, he joined the team as its pitching coach. His last baseball-related position was in 1970, when he served as general manager of the minor league Niagara Falls Pirates. Sal then worked as a salesman for a wholesale liquor distributor, and later as the membership coordinator for the Niagara Falls Convention Bureau, before retiring in 1979, at the age of 62. His good health ended abruptly in 1982, when he suffered a brain aneurysm and nearly died. After making a remarkable recovery, Sal enjoyed several more good years. But his physical and mental health declined, and he was placed in a nursing home in 1987, where he survived another five years, passing away on December 28, 1992, at age 75. |

|||||