|

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||||

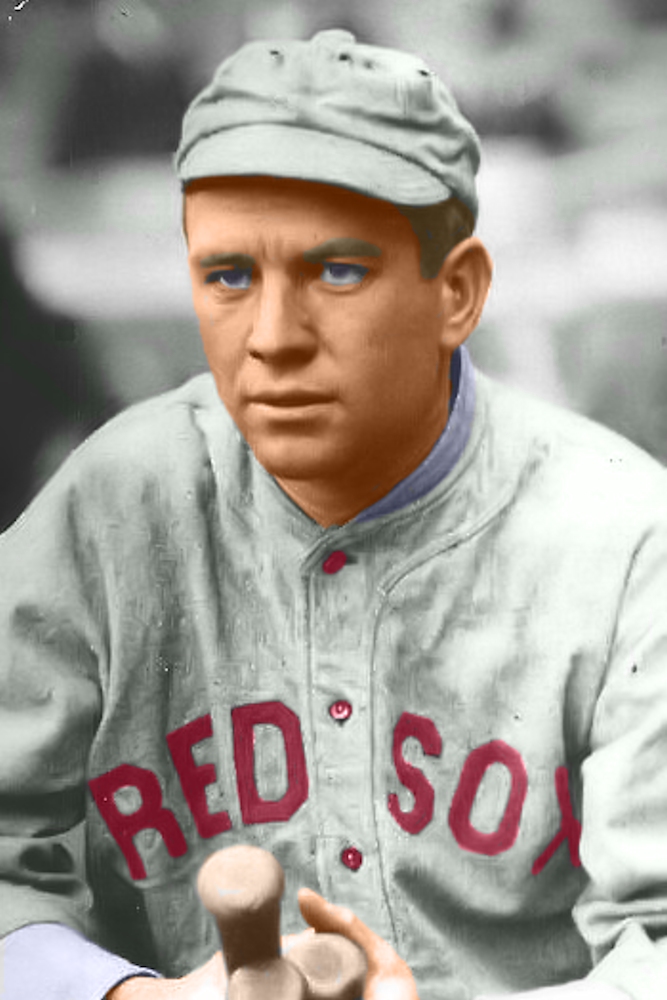

Tris Speaker, Ty Cobb’s friendly rival as the greatest center fielder of the Deadball Era, could field and throw better than the Georgia Peach even if he could not quite match him as a hitter. Legendary for his short outfield play, Speaker led the American League in putouts seven times and in double plays six times in a 22-year career with Boston, Cleveland, Washington, and Philadelphia. Speaker’s career totals in both categories are still major-league records at his position. No slouch at the plate, Speaker had a lifetime batting average of .345, sixth on the all-time list, and no one has surpassed his career mark of 792 doubles. He was also one of the game’s most successful player-managers. A man’s man who hunted, fished, could bulldog a steer, and taught Will Rogers how to use a lariat, Speaker was involved in more than his share of umpire baiting and brawls with teammates and opposing players. But when executing a hook slide on the bases, tracking a fly ball at the crack of an opponent’s bat, or slashing one of his patented extra-base hits, Speaker made everything he did look easy. Tristram E. Speaker was born on April 4, 1888, in Hubbard, Texas, a railroad town of 500 people 70 miles south of Dallas, to a family that had relocated from Ohio just prior to the Civil War. His father, Archie, whose two older brothers had fought for the Confederacy, was in the dry-goods business and died when Tris was 10. Tris’s mother, Nancy Jane, whose brother also fought for the South, kept a boarding house. A born right-hander, young Tris taught himself to throw left-handed when he twice broke his right arm after being thrown from a bronco. Soon he began to bat left-handed as well. Tris played football in high school and was captain and pitcher on his high-school baseball team. In 1905 Speaker entered the Fort Worth Polytechnic Institute (now Texas Wesleyan University), where he pitched for the school’s baseball squad, as well as for the Nicholson and Watson semipro club in Corsicana. Tris picked up extra money working as a telegraph lineman and cowpuncher. In 1906 Speaker wrote several professional teams asking for a tryout and was signed by Cleburne of the Texas League for $65 per month. Tris bombed as a pitcher – he lost six straight games and once reportedly gave up 22 straight hits, all for extra bases – but as an outfielder he hit .268 and stole 33 bases in 84 games. When the North Texas League and South Texas League were consolidated in 1907, Speaker moved to Houston and hit a league-leading .314 with 36 steals in 118 games. The Boston Red Sox purchased Speaker’s contract at the end of the 1907 season. He appeared in seven games for the big club, but hit only .158. Unimpressed with his play, the Red Sox did not send Speaker a contract for 1908. Speaker twice begged John McGraw for a chance to play for the New York Giants, to no avail, and was also rebuffed by several other major-league clubs. Finally, Speaker paid his own way to Boston’s Little Rock training camp to work out with the Red Sox. At the end of spring training, the Red Sox turned his contract over to Little Rock of the Southern Association as payment for the rent of the training field. There was one stipulation: If Speaker developed, Boston had the right to repurchase him for $500. Speaker led the Southern Association in hitting in 1908 with a .350 average stole 28 bases, and drew raves for his outfield play. Despite interest from the Pittsburgh Pirates, Brooklyn Superbas, Washington Senators, and, at last, the Giants, the Travelers sold Speaker back to Boston. Speaker hit only .224 in 31 games for the Red Sox in 1909, but was flawless in the outfield. Speaker further honed his outfield skills by working with Red Sox pitcher Cy Young. Speaker led Boston to world championships in two of the next seven seasons, 1912 and 1915, hitting above .300 every year and perennially ranking among American League leaders in most offensive and defensive categories. With teammates Harry Hooper and Duffy Lewis, Speaker formed one of the best fielding outfields in history. During this period Speaker led AL center fielders in putouts five times and in double plays four times. Twice he had 35 assists, the American League record. In 1912 Speaker, playing in every game but one, won the Chalmers Award as the League Most Valuable Player. He batted .383, third in the league behind Cobb and Joe Jackson, and led the league in doubles, home runs (tied), and on-base percentage. (“Spoke,” one of Speaker’s nicknames, came, ironically, from Speaker’s teammate and rival Bill Carrigan, who would yell, “Speaker spoke!” when Tris got a hit.) To cap it off, in the World Series against the New York Giants, Speaker got a key hit in the 10th inning of the decisive eighth game after his harmless foul popup fell untouched between first baseman Fred Merkle and catcher Chief Meyers. Given a second chance, Speaker singled in the tying run. Boston fans loved him. Speaker received $50 each time he hit the Bull Durham sign, first at the Huntington Avenue Grounds and later at Fenway Park. He endorsed Boston Garters, had a $2 straw hat named in his honor, and received free mackinaws and heavy sweaters. Hassan cigarettes created popular trading cards of Speaker depicting him running the bases. In the outfield Speaker played so shallow that he was almost a fifth infielder. “At the crack of the bat he'd be off with his back to the infield,” said teammate Joe Wood, “and then he'd turn and glance over his shoulder at the last minute and catch the ball so easy it looked like there was nothing to it, nothing at all.” Twice in one month, April 1918, Speaker executed unassisted double plays at second base, catching low line drives on the run and then beating the baserunner to the bag. At least once in his career Speaker was the pivot man in a routine double play. As late as 1923, after the advent of the lively ball forced Speaker to play deeper, he still had 26 assists. “I know it's easier, basically, to come in on a ball than go back,” Speaker said later. “But so many more balls are hit in front of an outfielder, even now, that it it’s a matter of percentage to be able to play in close enough to cut off those low ones or cheap ones in front of him. I still see more games lost by singles that drop just over the infield than a triple over the outfielder's head. I learned early that I could save more games by cutting off some of those singles than I would lose by having an occasional extra-base hit go over my head.” Almost 6 feet tall and a sturdy 193 pounds, Speaker batted from a left-handed crouch and stood deep in the batter’s box. He held his bat low, moving it up and down slowly, “like the lazy twitching of a cat’s tail,” according to an admirer, and took a full stride. “I don't find any particular ball easy to hit,” he said. “I have no rule for batting. I keep my eye on the ball and when it nears me make ready to swing.” Nevertheless, “I cut my drives between the first baseman and the line and that is my favorite alley for my doubles.” He was a remarkably consistent batter. In 1912, Speaker set a major-league record with three separate hitting streaks of 20 or more games, while his 11 consecutive hits in 1920 set a mark that went unsurpassed for 18 years. Speaker’s major weakness as a batter was the slow, high, curve. Despite the team’s success on the field, tensions were often high in the clubhouse. Speaker and catcher Carrigan never got along and had several brawls. Speaker was often not on speaking terms with Duffy Lewis, who, like Carrigan, was an Irish Catholic. (Religious differences had created cliques on the club, with Speaker siding with other Protestants including Joe Wood and Larry Gardner). The atmosphere grew more complicated with the arrival of Babe Ruth in 1915. Ruth crossed Wood and Speaker never fully forgave him. In his book Baseball As I Have Known It, Fred Lieb wrote that Speaker once told Lieb he was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. Although the Klan kept its membership rolls secret, Speaker’s alleged membership would not be surprising given that the Klan experienced a nationwide revival beginning in 1915, gaining much popularity with its anti-Catholic rhetoric. In addition, the Klan’s national leader from 1922 to 1939, Imperial Wizard Hiram W. Evans, lived near Speaker in Hubbard. Relations between the Grey Eagle and team president Joe Lannin were also far from warm. After the Red Sox World Series victory in 1915, Lannin angered Speaker by proposing that the outfielder’s salary be cut from about $18,000 – higher at the time than that of Ty Cobb – to $9,000, since Speaker’s batting average had declined three years in a row. (Lannin had raised Speaker’s salary in 1914 to keep him from jumping to the Federal League’s Brooklyn Club, which had offered Speaker a three-year contract for $100,000 to be its player-manager). When Speaker held out, Lannin traded him to Cleveland for Sam Jones, Fred Thomas, and $55,000. Speaker received a massive outpouring of affection from the fans when he returned to Boston in a Cleveland uniform on May 9, 1916, and even mistakenly headed toward the Red Sox dugout at the end of one inning. Boston pitchers, meanwhile, complained that without Spoke in center, they could no longer groove fastballs when behind in the count, certain that he would catch everything hit his way. The Red Sox won the World Series again, but Speaker became the idol of Indians fans and hit even better with his new club than he had in Boston. Speaker spent 11 seasons with the Indians, compiling a batting mark that averaged over .350. Speaker finished his major-league career with Cobb on Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics in 1928. He spent 1929 and 1930 as the player-manager of the Newark Bears in the International League, where he hit .355 and .419 in limited play. |

|||||