|

|

1939-1949 |

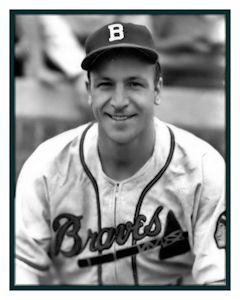

Although he was a four-time All-Star with the Boston Braves and respected

throughout baseball as an excellent defensive catcher and steady hitter, Phil

Masi is best remembered for being part of one of the most controversial plays in

World Series history.

During the bottom of the eighth inning in Game One of the 1948 Series between

the Braves and Cleveland Indians, Cleveland pitcher Bob Feller spun around and

threw to shortstop Lou Boudreau to try to pick Phil off of second base. Phil,

who was pinch-running for slow-footed starting receiver Bill Salkeld, slid back

to the bag and was called safe by umpire Bill Stewart, though most observers

believed he was out. The implications became huge moments later when Phil scored

the only run of the game on Tommy Holmes’ single, thus denying Hall of Famer

Feller his best chance to win a World Series contest. Back in ’48, bitterness

about the pickoff play had remained strong throughout the remaining five games

of the series.

Ironically, the decisive run that Phil accounted for in Game One would be the

only one he scored in that World Series. Interestingly, and long since

forgotten, is that Indians pitcher Bob Lemon and Boudreau picked Boston’s Earl

Torgeson off of second base in Game Two using the same play. Cleveland won that

game 4-1, and after the Indians captured the series it would have been logical

for fervor over the incident to die down.

As a 20-year-old in his first professional season, Phil hit .334 with 10 home

runs and 61 RBIs in only 96 games for Class “D” Wausau. Although he had started

as a catcher, Phil was a fulltime utility player during his second season with

Wausau in 1937. All told Phil had his finest minor league season at the plate in

’37, batting .326 and leading the league with 31 home runs in being named a

Northern League All-Star.

Following his 102-RBI performance with Wausau, Masi was purchased by the

Milwaukee Brewers, a Cleveland affiliate, and sent to Springfield of the

Mid-Atlantic League at the very end of the ’37 season. By 1938, Phil was

primarily a catcher. During that season his backup behind the plate was Jim

Hegan, who would be the opposing catcher when Phil’s Braves and his Indians

faced each other in the World Series 10 years later. While his offensive numbers

had fallen a bit for Springfield, Phil’s .308 batting average with 16 home runs

and 97 RBIs was enough to convince the Boston Bees (as the Braves were then

called) to sign him to a deal.

The Bees already had a surplus of catchers: the ’38 Boston roster.

Phil,

however, would not be deterred from the challenge, and Bees Manager Casey

Stengel noticed.

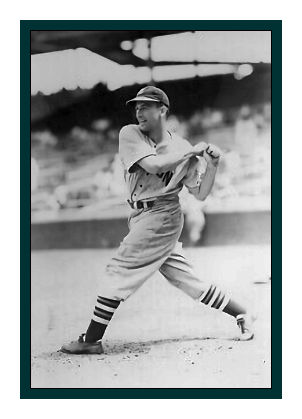

The right-handed hitting Phil debuted for the Braves as a defensive replacement

on April 23, 1939 in New York against the Giants. The next month, in his first

plate appearance, he hit a run-scoring double off of Bucky Walters. All told,

Phil batted .254 with just one home run and 14 RBIs in 46 games during his

rookie season, as Lopez played almost every day. Understandably, while he did

get a game-tying run in the ninth inning of the September 7, 1939 game against

Carl Hubbell — hitting the first pitch he saw to center field to score Max West

— he did not get much notoriety during his first season. When he slugged a home

run off of Brooklyn pitcher Hugh Casey on August 13, 1939, in fact, writer

Robert B. Cooke referred to him as “the obscure second-string catcher.”

For a while, things did not get much better. From 1940 through 1942

Phil

struggled woefully at the plate as a back-up player, posting batting averages of

.196, .222, and .218, respectively and never getting more than 180 at-bats in a

season. Hall of Famer Ernie Lombardi (in ’42) handled the bulk of the catching

duties. And although his offensive highlights were few during this period, Phil

in 1941 did break up Whitlow Wyatt’s no-hit bid for Brooklyn in 1941 as a

pinch-hitter with one-out in the ninth inning.

Phil served as a backup through 1942, but that season ended prematurely for him

on August 20th when he suffered a compound fracture of the little finger on his

throwing hand and returned home to Chicago to recover.

When defending NL batting champ Lombardi was traded to the Giants in early 1943,

he took over as the team’s regular catcher and responded with a .273 batting

average in 80 games. He also showed good speed for a catcher, stealing seven

bases during that summer. In fact, he occasionally was used as a pinch runner

throughout his career in Boston, a rarity for a catcher.

Still, it was the 5’10”, 180 lb. Phil’s ability to handle pitchers, rather than

his bat, that kept him in Boston’s lineup consistently for the next several

years. He made just two errors during the ’43 season, and tied Lopez (now with

Pittsburgh) for the league’s top fielding percentage of .991. He led the

National League in fielding in 1947, 1948, and 1950, while also leading all N.L.

catchers in assists in 1945 and putouts in 1946. This was especially impressive

considering that one of Boston’s top hurlers during part of this period was

knuckleballer Jim Tobin.

Masi also gained notoriety for his work catching 20-game winners Warren Spahn

and Johnny Sain. “Johnny Sain had an outstanding curve ball,” Phil noted, “but

he was harder to catch than Spahn because he would sometimes shake off the

signals. I’d call for a curve, but if the batter shifted his stance, Sain would

come in with a quick slider instead. He said he could get the batter out easier

that way, and since it worked most of the time, it was okay with me.”

Phil’s RBI totals improved in both 1945 and 1946, and he enjoyed his best season

at the plate in 1947 as the Braves continued their rise from perennial

second-division dwellers to a strong third-place club. In the middle of that ’47

season, Rumill made this observation:

For others, however, Phil’s numbers in 1947 stood out.

He had

career highs with a .304 batting average, which ranked 10th in

the National League, 125 hits, and nine home runs. He also struck out just 27

times in 411 at-bats and had 11 sacrifice hits, so even when he wasn’t getting a

hit, he was usually putting the ball in play (often to the team’s benefit).

While his offensive production tailed off in 1948, Phil still batted in 44 runs

and played solid defense for the pennant-wining Braves. He was chosen as a

National League All-Star for the fourth consecutive season that summer and got

his only career hit in All-Star play.

Masi’s offensive production continued to fall in early 1949. Through his first

37 games, the veteran catcher was batting only .210 with zero home runs and six

RBIs. With promising 19-year-old Del Crandall available as a potential

replacement, the Braves traded Phil to the Pittsburgh Pirates for outfielder Ed

Sauer on June 15, 1949.

Playing in the American League for the first time and starting again at catcher,

Phil’s career was further rejuvenated with the struggling White Sox in 1950. He

was Chicago’s starting catcher again in 1951. Following that season, when the

team acquired the much younger Sherm Lollar in a trade with the St. Louis

Browns, he became a backup once again.

Phil’s career had come full circle by 1952. At age 36 he hit .254, and at year’s

end he was released by Chicago. Phil finished his major league career with 917

hits, 27 home runs, 417 runs batted in, 45 stolen bases, and a .264 batting

average in 1,229 at-bats over 14 seasons.

Masi played one last season in 1953 with the minor league Dallas Eagles before

retiring from professional baseball, and he went out a winner.

Phil worked with a silkscreen printing firm in Chicago called Reliable Printing

Company until 1980. Phil Masi died of cancer on March 29, 1990 at age 74 at his

Mount Prospect, Illinois home.

|